Anger

Unlocking the Emotional Code of Abstract Art

Red is angry, yellow happy: Colors and lines communicate specific emotions.

Posted May 16, 2023 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Specific (sets of) colors are associated with different basic emotions.

- Artists and non-artists express emotions similarly with color and line.

- Visual language of abstract art is understood by a computer algorithm and by people.

The primary authors of this post are Dirk B. Walther (University of Toronto) and Claudia Damiano (KU Leuven)

Have you ever stood before an abstract painting, feeling a surge of emotion but struggling to explain why? The power of abstract art lies in its ability to convey meaning without depicting a specific subject matter. New research published in the Journal of Vision examines how people connect particular colors and lines with emotions in abstract art. It is easy to imagine that we associate certain features of paintings with specific emotions, like dark sharp scribbles with anger, and bright colors with joy, but how expressive are these features really for communicating emotions in abstract art?

To answer this question, Claudia Damiano, doctoral student at the University of Toronto, and Pinaki Gayen, a visiting art student from the Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur, set up shop at OCAD (Ontario College of Art and Design) University, and asked arts students to make abstract drawings depicting six fundamental emotions: anger, disgust, fear, sadness, joy, and wonder—first using only pencils, then using colorful pastel crayons. The researchers then repeated the experiment with non-arts students at the University of Toronto.

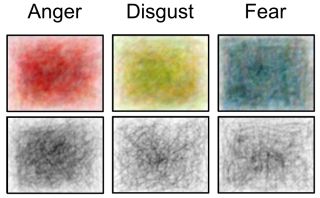

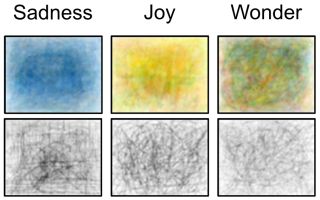

The researchers quantified the colors and lines in the drawings with computational algorithms—the frequency of pixels of particular colors, the density and number of contour lines, as well as their angularity, length, and orientations. The results showed systematic use of specific colors and line features to portray each emotion.

People used red and black for anger; brown, green, and ochre for disgust; black, gray, and blue for fear; and yellow, orange, cyan, and pink for joy and wonder. Sharp, jagged, short lines were generally associated with negative (unpleasant) emotions, and long, curvy lines with positive (pleasant) emotions. Interestingly, how art students and non-art students portrayed different emotions was remarkably similar. This suggests that people with and without formal training in the arts use color and shape to express emotions intuitively.

However, it is one thing to use color and lines to express emotions and another how successful this approach is to actually convey emotions. The first part of the study addresses what people do in trying to express emotions (e.g., what colors they use), but successfully conveying emotions means that viewers recognize the desired emotions.

To test viewers' reception, researchers used a computer algorithm to try to predict specific emotions from individual drawings. The algorithm compared each individual drawing to the composite of other drawings and tried to guess the feeling being expressed. The algorithm succeeded in approximately half the cases, when random guessing would only be correct 17% of the time. The mistakes were not random. Rather, fear was confused for sadness and wonder for joy due to their similar color palettes.

The algorithm fared a bit better for the drawings by the non-arts students than for those by arts students, likely due to arts students showing their unique personal styles in their drawings. In other words, arts students’ drawings were less similar to each other than those by non-arts studentsmand thus were harder to interpret. Overall, emotions were more easily predictable from color drawings than from line drawings, suggesting that colors are more effective than line features at conveying emotions, at least according to a computer.

How do these predictions fare in the real world? Researchers next asked people—university students in Belgium—to share what emotions they saw in the drawings. The students viewed the drawings created by the Canadian participants one at a time and chose the emotion that they thought was depicted from a list of six options. Their accuracy was similar to that of the computer algorithm. Again, color drawings were easier to interpret than line drawings, and emotions were recognized correctly more often in drawings by non-arts students than by arts students.

The findings suggest that people can intuitively understand the emotional content of abstract art and that certain visual cues are effective in conveying specific emotions. These results support the simulation theory in emotion science, which predicts that our abstract feature-emotion associations reflect associations in the real world, such as a person's face turning red when they are angry.

By demystifying the emotional language of abstract art, this research has the potential to open up new opportunities for interdisciplinary collaborations and applications in the real word —ranging from make-up to effectively convey emotions in stage or screen performances to the use of colors and shapes to convey emotions in advertisement or communications (e.g., yellow for joy about consumer products, red to call for action against injustice). Interior designers and architects could harness the emotional power of lines and colors to create environments that elicit specific responses—calming for airports or transit stations, wonder for educational settings, or joyous for retirement communities.

Ultimately, this work2 serves as a reminder of the profound connection between the visual world and our inner emotional landscape. As we learn how emotions are expressed and successfully conveyed to others, new questions emerge about the power of art. Aesthetic cognitivism3 is an idea born in philosophy which states that engagement with the arts not only moves us emotionally but also creates cognitive benefits, such as gaining new understandings and enhancing thinking abilities (e.g., creativity). Emotions intensify engagement with art and can open a door to exploring different benefits of art on its audience.

References

1. Johnson-Laird, P. N., & Oatley, K. (2021). Emotions, simulation, and abstract art. Art & Perception, 9(3), 260-292.

2. Damiano, C., Gayen, P., Rezanejad, M., Banerjee, A., Banik, G., Patnaik, P., Wagemans, J. & Walther, D. B. (2023). Anger is red, sadness is blue: Emotion depictions in abstract visual art by artists and non-artists. Journal of Vision, 23(4), 1-1.

3. Goodman, N. (1978). Ways of worldmaking. Hackett.