Media

The Psychology of Laurel and Yanny

Why do some people hear Laurel but others Yanny?

Posted May 18, 2018

A few years ago, social media erupted in disbelief over the color of a dress. About a week ago, the auditory analogue of ‘the dress’ was posted on Reddit, Instagram, and Twitter. It’s an audio clip in which the name being said depends on the listener: some hear “Laurel”, others “Yanny” (or something else entirely).

Listen to the original audio clip here.

Supposedly, it was recorded from a Text-To-Speech engine from a vocabulary website (vocabulary.com), pronouncing the noun “laurel”, but playing through speakers. But how come some people hear “Yanny”, when it should be “Laurel”?

This may have to do with the ‘technical’ properties of the sound. Analysis of the frequencies in the sound suggests that the higher frequencies (>1000 Hz) are more like “Yanny," but the lower frequencies (<1000 Hz) are more like “Laurel." It could be that playing “laurel” over speakers and re-recording it introduced high-frequency noise in the recording, which emphasized the higher frequencies. Now some listeners (for instance, young adults vs. older adults) are simply better at hearing these higher frequencies, or weigh them more heavily in perception than others, leading ‘high-frequency’ people to report Yanny, where ‘low-frequency’ people hear Laurel.

Interestingly, this social media hype is a great example of the kind of stimuli psycholinguists and phoneticians use in their experiments. The sound is ambiguous: It is not quite Yanny and it’s not quite Laurel; it’s kind of in between. Series of ambiguous speech sounds are used very often in psycholinguistics to understand the acoustic cues people use to perceive the ‘letters of speech.’ Often, researchers take one word (a clear Yanny) and another word (a clear Laurel) and artificially create sounds that fall in between those two endpoints. This is called a phonetic continuum, typically varying one particular acoustic dimension (for instance, the intensity of some frequencies, the duration of segments, etc.).

Here’s how this would work for the Laurel/Yanny sound: First reducing the higher frequencies, and then gradually step-by-step emphasizing the higher frequencies leads to a continuum from more Laurel-like (step 1; reduced higher frequencies) to more Yanny-like (step 6; emphasized higher frequencies).

Listen to step 1 here (most Laurel-like).

Listen to step 2 here.

Listen to step 3 here.

Listen to step 4 here.

Listen to step 5 here.

Listen to step 6 here (most Yanny-like).

A similar continuum can be created for many speech sounds. To demonstrate this especially for the British Royal Family, here’s a 3-step continuum from Harry-to-Meghan. It combines the higher frequencies from Harry with the lower frequencies from Meghan. Step 1 is more Harry-like because most of the high frequencies are from Harry. Step 2 is kind of in between, and Step 3 is more Meghan-like, with the high frequencies mostly from Meghan.

Listen to step 1 here (most Harry-like).

Listen to step 2 here (ambiguous).

Listen to step 3 here (most Meghan-like).

But can we actually make the same sound be perceived differently in different situations? Yes, we can. We know that the perception of speech sounds is influenced by the surrounding acoustic context. The same sound can be perceived differently when, for instance, the acoustics of a precursor sentence are changed.

To demonstrate this with the Laurel/Yanny sound, a short online experiment was run in which listeners heard the same Laurel-to-Yanny continuum as before, but this time preceded by a 7-digit telephone number (496-0356). So people heard things like: “496-0356 Laurel”. Sometimes the higher frequencies in the digit sequence (>1000 Hz) were attenuated (filtered out; low-pass filter at cut-off frequency of 1000 Hz), sometimes the lower frequencies were attenuated (high-pass filter at cut-off frequency of 1000 Hz). Click here to try this online test yourself.

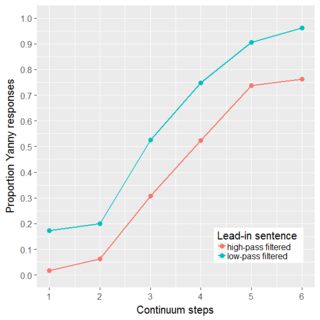

The results from 62 listeners are shown here in terms of the proportion of Yanny responses. We see that on the left side of the continuum, most people report Laurel (low proportion Yanny responses), and on the right side of the continuum, most people report Yanny – in line with what was just argued about the continuum. However, the acoustics of the lead-in telephone number can actually bias participants’ perception (confirmed by statistical GLMER analysis; precursor effect, p < 0.001): when the lead-in precursor has the higher frequencies attenuated, this makes the higher frequencies in the Laurel/Yanny continuum stand out more, leading to slightly more Yanny responses in the low-pass condition (i.e., the blue line is above the red line). Similarly, when the lead-in precursor has the lower frequencies attenuated, this makes the lower frequencies in the Laurel/Yanny continuum stand out more, leading to more Laurel responses in the high-pass condition.

So what can we conclude? Well, artificially emphasizing the higher frequencies leads to more Yanny responses (as evidenced by the continuum). Moreover, making people's ears more sensitive to the higher frequencies in the Laurel/Yanny word by first attenuating higher frequencies in a lead-in precursor also leads to more Yanny responses (based on the precursor effect). But maybe the most striking conclusion of the entire Laurel/Yanny hype is that it shows that even phonetics can be a trending topic on Twitter.

Facebook image: marienalien/Shutterstock