Race and Ethnicity

Do You Suffer from Racial Paralysis?

There are no-win race-related decisions, and they matter for democracy.

Posted July 11, 2018

Confession: I suffer from racial paralysis at times.

Many people do, and you'll see later that for that reason I think racial paralysis is a serious problem for democracy.

Racial paralysis is a term for some people’s tendency to opt out of situations that require decisions seemingly made on the basis of race. For example, at lunch you grab your fast food and look for a place to sit at the restaurant. There are only two open seats, one next to a black guy and one next to a white guy. If you choose to sit by the white guy, you worry you may look like a racist because you “shunned” the black guy. If you choose to sit by the black guy, you worry you may look like you’re trying too hard to be “politically correct” and not to look like a racist.

So, you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t. All you want to do is be viewed as unbiased. But regardless of which seat you choose (and how you truly feel), you believe you’re going to be viewed with a jaundiced eye by at least some of the people in the restaurant. So, you opt out and decide to eat your lunch at your desk.

In the political realm, when might someone think about “opting out” of a discussion? How about when asked about immigration when popular narratives are that you’re a cold-hearted racist if you oppose more immigration or that you’re flouting the rule of law for political purposes if you support more immigration. Or when asked about affirmative action when either position, support or opposition, suggests you believe in giving one race an advantage over another?

The Scientific Evidence for Racial Paralysis

Skeptical? A team of researchers from Harvard, Columbia, the University of South Florida, and Yale published an article in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience in 2013 entitled, “An fMRI investigation of racial paralysis” (full article). Like most good research, the researchers measured their concept from more than one perspective.

First, they used behavioral measures. In their main study they showed non-black subjects pairs of pictures of individuals and asked them to indicate which individual in each pair best exemplified a series of characteristics. The characteristics were related to black stereotyping, such as, intelligent, motivated, and articulate, and unrelated to black stereotyping, such as, outgoing, quiet, and restless. Of course, the pairs of pictures were choices between two black men, two white men, and one black and one white man.

They found that their subjects were much more likely to refuse to make a choice between the pictures (i.e., opt out) when the choice was cross-race (i.e., between a black and white man) than when it was same race (i.e., between either the two black or two white men). This was especially true when the characteristic was related to black stereotypes, further confirming sensitivity to a race-related choice.

In a similar study but asking about which individual would perform better in college, only 18 percent of subjects refused to indicate which individual they thought would do better when the individuals were of the same race, but 54 percent (three times as many) refused when the individuals were of different races.

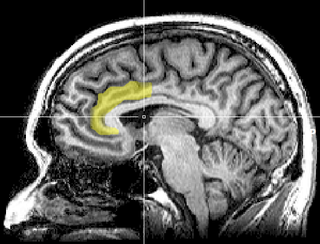

Next, they looked for neurological evidence of the existence of racial paralysis using fMRI brain scans. The researchers expected racial paralysis to activate the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which tracks conflict and signals the need for impulse control, and the prefrontal cortex, in particular those parts that support deliberation, inhibition, and threats to normative and moral values.

Scanning subjects while they completed the black stereotyping task involving the same- and cross-race pairs of pictures mentioned above, they found that the cross-race choices tended to stimulate a stronger neurological response than the same-race choices.

Overall, although the samples were small and research findings need to be replicated to be trusted, the researchers present a nice convergence of behavioral and biological evidence that suggests racial paralysis actually exists in some people.

This Hurts Democracy

The consequences of these findings reach farther than psychological science. If you believe, as I do, that informed debate and citizen participation are vital to democracy, then widespread racial paralysis, or the tendency of a large proportion of citizens to opt out of important debates and decisions that may have racial overtones (e.g., social welfare, immigration, the justice system, and affirmative action), is of critical concern. The silent are simply trying to be what we want good citizens to be, unbiased. More consequentially, though, when few voices are raised, it’s often the most extreme voices that are heard.

References

Norton, Michael I., Malia F. Mason, Joseph A. Vandello, Andrew Biga, and Rebecca Dyer. 2013. “An fMRI investigation of racial paralysis.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 8(4): 387-393.