Sexual Orientation

Wonder Woman: A Superhero's Sexual Orientation

Can a character's sexual orientation conjure cognitive dissonance?

Posted June 17, 2022 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

People throughout the world love Princess Diana of Themyscira, a.k.a. Wonder Woman. She is strong and kind, a mentally healthy hero who embodies the virtues identified in positive psychologists' Character Strengths & Virtues manual, the CSV (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), as psychologist Mara Wood notes throughout Wonder Woman Psychology: Lassoing the Truth (e.g., Wood, 2017).

Diana exemplifies the virtues of justice, temperance, courage, wisdom and knowledge, transcendence, and humanity as described in the CSV, along with many associated strengths. In order to keep her interesting and to make her resonate with audiences everywhere, storytellers must sometimes walk a fine line when depicting such a paragon of many virtues. Though sometimes they fall short when telling her tales, they've nevertheless managed to keep her appealing enough that she is one of only three superheroes to stay consistently in print every year since the early Golden Age of Comics (the other two being Superman and Batman). She is a wonder that endures.

Sometimes, though, she is also controversial.

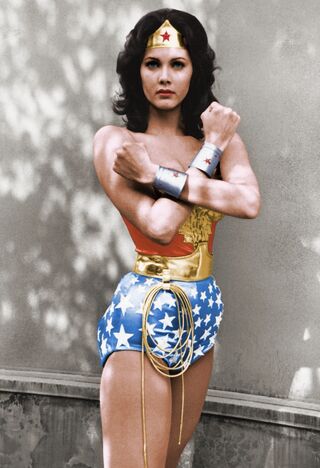

Recently Lynda Carter, who played the superhero Wonder Woman on television from 1975 to 1979, tweeted an illustration of Wonder Woman and said, "Happy Pride! So excited to celebrate with all my LGBTQIA+ friends and fans." A few of Carter's fans objected. One responded with disappointment, wondering why Carter would "use Wonder Woman to promote Gays, Lesbians, 'bisexuals' as you so said Wonder Woman is'" and insisting that Wonder Woman is "not a superhero for gays." Carter replied, "You're right. She's a superhero for bisexuals!" She added, "I didn't write Wonder Woman, but if you want to argue that she is somehow not a queer or trans icon, then you're not paying attention. Every time someone comes up to me and says that WW helped them while they were closeted, it reminds me how special the role is."

Along the way, she linked a Polygon article quoting the Wonder Woman comic book's writer Greg Rucka, establishing that the character is canonically queer. The fan soon apologized to Carter, but why would someone react with such distress in the first place?

We need hope. We seek inspiration. We admire and sometime try to emulate role models. Those role models may help us become better people as they influence our hopes, aspirations, morals, opinions, and interests (Brown & Trevino, 2014; Sonnentag & McDaniel, 2013; Young et al., 2013). They can also help us become conscious of the examples we, in turn, set for others. We yearn for something and someone to show us a sign that the world and we ourselves can be better.

Sometimes the source that inspires us can be a figure whose status lies outside anything that we might ever achieve. Sometimes it simply excites us to know that someone like that exists in this world or, in the case of our fictional heroes, to discover imaginary exemplars who amaze us. We feel especially inspired when such a person shares qualities that remind us in any way of ourselves (adapted from Langley, 2017, p. 250; 2019, p. 201).

We want our heroes to embody the values we hold dearest. They represent enough of those values for us to admire them, and so we want to assume they adhere to our other values as well. When one of our heroes deviates from our preferences and assumptions, this can create a state of cognitive dissonance, stress over inconsistency within our cognitions or between our cognitions and experience (Cooper, 1992; Festinger, 1957; Stone & Focella, 2011). A person can hold contradictory views as long as they're not forced to see the contradiction. One way to do that is compartmentalize those views and only consider each separately from the other. No dissonance is suffered until the day comes when reality defies oversimplified compartmentalizations and makes the person consider the different views and associated actions in conjunction with each other. Maybe the person finds out that a hero who saved a child's life belongs to the "wrong" political party, or that a good friend has always been a member of an ethnic group that the person in question has hated. Cognitive dissonance often arises as we learn more about other people because people are complicated.

When confronted with assertion that a heroic figure is a gay icon, the homophobic fan may have difficulty wrestling with the idea that heroism can include such a thing. The stress of dissonance is greatest when both of the seemingly contradictory positions figure into how we see ourselves. Because our values are important to our self-concepts, our positions regarding those whom we adore and those whom we disdain also impact our self-esteem. The discovery that someone belongs to both groups can unnerve us.

Changing attitudes to match actions lets people trick themselves to feeling they were not hypocrites, as if they'd already thought in accordance with their outward behavior. Likewise, when new information contradicts an existing cognitive schema (a mental pattern of association, per Piaget, 1952), it tends to be easier to assimilate the new information into the existing associations than it is to change the schema itself, to accommodate the new information.

Changing the schema, changing a piece of how the person interprets the world, is more likely to mean changing an aspect of self-concept. When able to think of them as unrelated matters, no conflict over them will stress a fan who holds both great adoration for the hero and strong views regarding a topic such as sexual orientation feels no conflict. When forced to see them as interrelated, when those titanic emotions clash, that is when cognitive dissonance strikes.

The person who takes the tougher path, by changing actions to become less hypocritical or by adapting schemas to accommodate new facts, can develop greater ability to see the world for the complex thing it is, to discern greater nuances in human nature, to learn new lessons, and to grow more mature as a human being. Of course a hero can be gay. A hero can be many different things in life because a hero has to be human, and humans come in a variety of wonders.

References

Brown, M. E., & Trevino, L. K. (2014). Do role models matter? An investigation of role modeling as an antecedent of perceives ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(4), 587-598.

Cooper, J. (1992). Dissonance and the return of the self-concept. Psychological Inquiry, 3(4), 320-323.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Langley, T. (2017). Snapping necks and wearing pants: Symbols, schemas, and stress over change. In T. Langley & M. Wood (Eds.), Wonder Woman psychology: Lassoing the truth (pp. 247-257). Sterling.

Langley, T. (2019). A source of inspiration. In T. Langley & A. Simmons (Eds.), Black Panther psychology: Hidden Kingdoms (pp. 200-201). Sterling.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues. American Psychological Association.

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Sonnentag, T. L., & McDaniel, B. L. (2013). Doing the right thing in the face of social pressure: Moral rebels and their role models have heightened levels of moral trait integration. Self & Identity, 12(4), 432-446.

Stone, J., & Focella, E. (2011). The meaning of life and Adler's use of fictions. Journal of Individual Psychology, 67(1), 13-30.

Wood, M. (2017). Final word: Transcendence. In T. Langley & M. Wood (Eds.), Wonder Woman psychology: Lassoing the truth (pp. 317-319). Sterling.

Young, D. M.,, Rudman, L. A., Buettner, H. M., & McLean, M. C. (2013). The influence of female role models on women's implicit science cognitions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(3), 283-292.