Trust

Who Do You Trust?

The psychology of trust and how to build it across cultures

Posted June 5, 2017

“To be trusted is a greater compliment than being loved,” wrote the 19th century Scottish poet George MacDonald. A bit more recently, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio concluded that, “there is no love without trust.” Whether or not these high accolades bestowed on trust ring true for all of us, both trust and love share the burden of being among our most affectively-loaded (albeit cherished) concepts. We know how it feels to trust and to be trusted, yet, we may stumble to articulate its meaning.

What is trust?

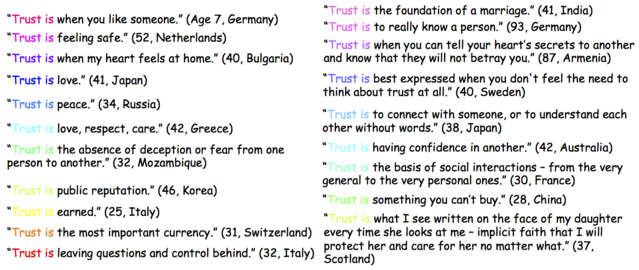

I asked people from different corners of the world to complete this sentence “Trust is …” to catch a glimpse of trust in its many hues.

The word trust has its origins in the Indo-European root droust meaning “solid” and “lasting.” In Old English it referred to “confidence” and “dependence,” while in the 14th century Chaucer used the word trust to mean “virtual certainty and well-grounded hope.” The old connotations of the word have preserved to the present day, where trust as we know it is a “lubricant of social interaction” and an essential ingredient for thriving interpersonal relationships – from families, to friends, to organizations. Trust and reciprocity are considered to be the “basis of all human systems of morality.” Not only is trust an elixir for social functioning, but as part of a nation’s social capital, trust affects vital economic variables such as GDP growth and inflation rates.

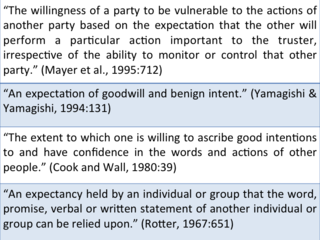

In the scholarly literature, trust has been defined as:

Researchers in social psychology differentiate between two kinds of trust – affective and cognitive. Cognitive trust is based on our knowledge and evidence about those we choose to trust. Affective trust, on the other hand, is born out of our emotional ties with others, including the security and the confidence we place in others based on the feelings generated by our interactions. Sometimes, the differences of cognitive and affective trust have been described as trusting with your head (cognitive) and trusting with your heart (affective).

Trustworthiness is an esteemed virtue among friends and employers alike and it comes with a host of perks. Those with more trust are less likely to lie, and appear more ethical, more attractive and even happier (see review in Rotter, 1980). Moreover, someone who is deemed trustworthy appears to epitomize a set of positive characteristics, including ability (skills and competencies), benevolence (the will to do good), and integrity (adhering to principles).

The psychology of trust

How do psychologists and economists study trust? One of the most prevalent routes has been via the trust game. In this game, two players sequentially send money to each other. The first player can choose to place a large sum of money in the hands of the second player. Because the second player is not obliged to reciprocate (and can keep all gains for herself), the possibility of betrayal of the initial investment simulates many real-life situations involving trust. The results of hundreds of studies with trust games have yielded fascinating insights into the psychology and neurobiology of trust. For instance:

- The hormone and neurotransmitter oxytocin increases trust, likely by suppressing the neural systems that regulate our fear of betrayal.

- When we feel negative emotions, we are less likely to trust others.

- We may base our decisions about whom to trust on their attractiveness, how much they resemble our kin members, and their facial features. One study, for instance, showed that males with relatively wider faces (a feature associated with testosterone) were less likely to be trusted during the trust game.

- Women tend to reciprocate their wealth in trust games more than men.

- People may have a “preconscious friend-or-foe mental mechanism” that helps them to evaluate others during interactions (partners are trusted more than opponents).

- Genetic variation and heredity influence how people invest or reciprocate during trust games.

- Trust in strangers increases from childhood to early adulthood, and then remains more or less stable in adulthood.

- There are differences in levels of trust across cultures. For instance, Americans are more trusting of others compared to the Japanese and the Germans during trust games.

Trust across cultures

Trust also plays a critical role in the dynamics of leading and working with global teams. In her book The Culture Map, Erin Meyer identifies trust as one of the 8 scales to consider for improving effectiveness in multicultural business settings. What’s one of the biggest challenges of building trust across cultures? According to Meyer, it’s the different ways people come to feel trust around the world.

“What we have seen in research, is that in some parts of the world like the US, UK, Australia or Northern Europe, people have a tendency to separate cognitive trust for work and affective trust for home. In Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East there is more of a tendency to weave cognitive and affective trust together in the work environment.”

What, then, are some steps we could take to build trust across cultures? Erin Meyer explains:

“Let’s consider an example. I recently worked with a group of Americans who were pitching business in China. They had prepared a beautifully polished and well-rehearsed presentation. But they didn't get the business, since their Chinese clients chose to work with a group from Malaysia whose price was even higher than the Americans’. The reason is because the Chinese trusted the Malaysians more, since in addition to having a nice product, the Malaysians had spent a significant time sharing meals together and developing friendships, thus establishing affective trust.”

“So, the first step is to determine whether the individuals you are working with are from task or relationship-oriented cultures*. Then, you can make slight adjustments to the way you organize your meetings to maximize trust.”

“When working with an emerging market culture, for example, you could set up opportunities even before the meeting or the presentation. We have a tendency in the US (the most task-oriented culture in the world) and Europe to first do the work, and then go out to eat. But you can do the opposite. We can first get to know one another and build up trust, and then get down to business. Find opportunities outside the office to approach your international colleagues not like business partners but like friends. We can also choose our communication medium – telephone over email, Skype over telephone – to spend as much time as possible learning about the individuals we are working with, instead of focusing on getting the task completed.”

“On the other hand, if you are from India and are doing business with Germany, the recommendation would be the opposite. Instead of investing a lot of time into getting to know one another, focus on getting a really great product and presentation. Affective trust will follow. When working with multinational teams, have a blend of cognitive and affective tasks to build trust. Set up meetings with brief check-ins about what is going on in your team members’ lives before you get down to business. When you get back to the team meeting after the affective bond was built, then you can focus on the task at hand.”

Trust, then, whether between global teams or neighbors, is among our most invaluable commodities. As to how to decide whose hands will cradle our trust and in whose hands it will be crushed, Ernest Hemingway’s wisdom offers a clue: "The best way to find out if you can trust somebody is to trust them."

* More information about where various cultures rank with Erin Meyer’s Country Mapping tool can be found here (password: PsychologyTodayJune).

Many thanks to Erin Meyer for being generous with her time and insights. Erin Meyer is the author of The Culture Map and is a professor of Organizational Behavior at INSEAD. Many thanks also to everyone from around the world who entrusted me their definitions of trust.

References

Baumgartner, T., Heinrichs, M., Vonlanthen, A., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2008). Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans. Neuron, 58(4), 639-650.

Burnham, T., McCabe, K., & Smith, V. L. (2000). Friend-or-foe intentionality priming in an extensive form trust game. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 43(1), 57-73.

Cesarini, D., Dawes, C. T., Fowler, J. H., Johannesson, M., Lichtenstein, P., & Wallace, B. (2008). Heritability of cooperative behavior in the trust game. Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences, 105(10), 3721-3726.

Cook, J., & Wall, T. (1980). New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non‐fulfilment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53(1), 39-52.

Croson, R., & Buchan, N. (1999). Gender and culture: International experimental evidence from trust games. The American Economic Review, 89(2), 386-391.

Damasio, A. (2005). Human behaviour: brain trust. Nature, 435(7042), 571-572.

DeBruine, L. M. (2002). Facial resemblance enhances trust. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 269(1498), 1307-1312.

Engelmann, J.B., Meyer, F., Ruff, C.C., Fehr, E. (2017). The Neural Circuitry Of Emotion-Induced Distortions Of Trust. Biorxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/129130

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity (No. D10 301 c. 1/c. 2). Free Press Paperbacks.

Gambetta, D. (1988). Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations.

Johnson, D., & Grayson, K. (2005). Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. Journal of Business Research, 58(4), 500-507.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251-1288.

Kosfeld, M., Heinrichs, M., Zak, P. J., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435(7042), 673-676.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709-734.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect-and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24-59.

Meyer, E. (2014). The culture map: Breaking through the invisible boundaries of global business. PublicAffairs.

Naef, M., Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2008). Decomposing trust: explaining national trust differences. International Journal of Psychology, 43(3), 577.

Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (2000). Shrewd investments. Science, 288(5467), 819-820.

Porta, R. L., Lopez-De-Silane, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1996). Trust in large organizations (No. w5864). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Rotter, J. B. (1980). Interpersonal trust, trustworthiness, and gullibility. American Psychologist, 35(1), 1.

Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. Journal of Personality, 35(4), 651-665.

Stirrat, M., & Perrett, D. I. (2010). Valid facial cues to cooperation and trust male facial width and trustworthiness. Psychological Science, 21(3), 349-354.

Sutter, M., & Kocher, M. G. (2007). Trust and trustworthiness across different age groups. Games and Economic Behavior, 59(2), 364-382.

Wilson, R. K., & Eckel, C. C. (2006). Judging a book by its cover: Beauty and expectations in the trust game. Political Research Quarterly, 59(2), 189-202.

Yamagishi, T., & Yamagishi, M. (1994). Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motivation and Emotion, 18(2), 129-166.