Optimism

Everyone Is Just Waiting

Waiting for the future can seem to be a bleak prospect. Or have we got it wrong?

Posted March 29, 2020

Cynthia Hammond is a psychologist and a BBC broadcaster. In 2012, she published a fascinating book called Time Warped: Unlocking the Mysteries of Time Perception. One of the many intriguing asides in Time Warped tells us, "contemplating the future could be the brain's default mode of operation."

The future? I'd always thought that the brain was mostly interested in the here-and-now, in what we're up to right at this minute. But no, Cynthia Hammond explains, that's not the case. This focusing of the brain on the future, she goes on to say, "is not wasteful daydreaming or, as the phrase goes, a case of 'wishing our lives away.' Mental time-travel into the future matters... It affects our judgments, our emotional states, and the decisions we make."

Maybe there's another way you might want to describe this tendency of the brain to focus on the future. This might make the default future mode easier to get a grip on. The brain, you could say, is not just keen on the future, it's also pretty keen on "staying where it is [right in the present] until a particular time or event [in the future]." That description may sound a little cumbersome. It's the definition from the Oxford English Dictionary for waiting.

And waiting, when you come to think of it, is what the brain is doing when it focuses on the future. It's pausing and focusing and waiting for what will come. It appears that we are both, us and our brains, skilled and experienced at hanging around in this anticipatory mode. Just as well. For lots of us, right at present, it's all we're doing.

How much of our lives are taken up by this forward-looking way of thinking? Claudia Hammond offers some figures: "on average people think about the future 59 times a day or once every 16 minutes during waking hours." If you have a deep worry, just as we all do right at the minute, then these statistics suggest an awful lot of worry is going to play out in those 59 times. The same would apply to something very pleasant that you are waiting for—like getting home from work or eventually quitting work.

But that's not quite how it is right now. Most of us have quit work and are home, in some manner or another. As for those figures, imagine that all of the 59 future imaginings you have per day are devoted to just one worry, say the virus right now. That's 21,535 times in the year.

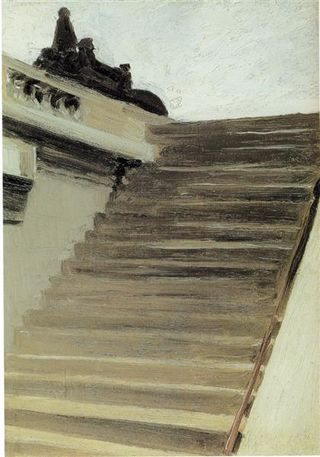

How does Cynthia Hammond's default mode of operation, her version of mental waiting work? Take a look at the picture by Edward Hopper (America's master painter of waiting), and maybe it will be clearer. Steps in Paris is an image of a set of empty stairs in Paris in 1907.

I believe that when your brain looks at the picture, it starts to look to the future. It goes into that default mode Cynthia Hammond was speaking of, and it starts to wait. It asks as it waits: What's at the top of those stairs? Anything? Anyone? Is there a group of people just about to come down? Are they friendly or hostile? Will I be stuck here on my own?

Viewing the painting makes you feel as if you're there in Paris, mentally waiting for an answer. Sad to say, Hopper's painting creates an atmosphere that's just like what we're getting used to in our suddenly empty cities. When you see those empty stairs or empty streets or empty shops in your city, your brain, in its future-focus mode, is waiting and wondering—what comes next?

My sister was telling me about how she feels in her hometown of Melbourne in Australia right now. It's a bit like a Hopper painting, she said to me, if you can get out from lockdown to see it. "Hold on is what we're doing here," she said. "The three-quarters empty supermarket shelves, the fights over toilet paper, etc., and all our public places closed from today—just when I thought I'd go into the city. No—we're meant to stay home and shop locally if there's anything left." It's the same everywhere. In better times, an awful lot of that mental waiting would be devoted to something good.

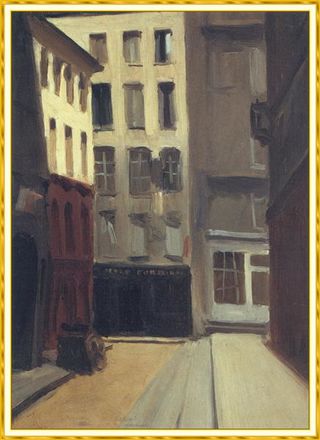

Let's have one more of Edward Hopper's empty paintings about waiting—paintings about one of the brain's unexpected default modes. This next one was done a year after his Steps in Paris, and it's called Paris Street. Hopper was living in France in this period.

Paris Street brings up the same sorts of questions as Steps in Paris. It asks: What's around the corner at the end of the empty street? Some friendly or some hostile people? Or is everyone inside and asleep or just waking up or off on holidays? Where is everyone?

Viewing the painting makes you feel as if you're there in Paris, waiting for an answer. Hopper played with waiting and emptiness in his paintings throughout the rest of his career. If I could show you some (and there are lots) from later in his long life (1882-1967), you'd see that his vision didn't change. But I'm stymied by copyright. We'll have to wait a while for the others to be released onto the public domain. In the meantime, you can see some of them on the internet: The Street Corner (1923), City Roofs (1936), The City (1927), Gas (1940—everyone's favorite, I reckon).

Dr. Seuss is a more famous American than Edward Hopper. My title, "Everyone is just waiting," comes from his book, Oh the Places You'll Go. "Everyone is just waiting" is a chorus in his poem about "The Waiting Place," a boring, dreary area that seems to exist to hold back the optimistic graduating kid of Oh the Places You'll Go.

"The Waiting Place" is a region that Edward Hopper might have admired. It's almost a parody of the one lots are in now. In "The Waiting Place," there are people stuck on a broken-down bus, a man is fishing in a sewer hole, a vast queue of people is waiting to get into a single toilet, a soldier is waiting for a disconnected phone to ring. But none of these fixtures manages to hold Dr. Seuss's kid back. "Somehow you'll escape all that waiting and staying," says Dr. Seuss. And on that little kid goes into the future, exercising Cynthia Hammonds's default mode of operation for the brain, waiting for the future.

Dr. Seuss gets waiting wrong. Waiting's not about "all that staying." But you've got to admire Dr. Seuss's optimism. He believes that you can get away from all the gloom of "The Waiting Place." You'll turn it to your own advantage, and you'll move on. Waiting for Dr. Seuss ends up as a very good thing, in fact, if it can push you into the future.

Who'd say whether there's help in "The Waiting Place" for us in our empty Hopper-like cities right now? But it feels that way. It's more a matter of how you manage this mental waiting, how you try to wait well perhaps, and whether you can struggle to turn it to your own advantage. Who knows what's really waiting at the top of Edward Hopper's Steps in Paris? Maybe it's his best friends?