Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Do Psychiatric Service Dogs Really Help Veterans with PTSD?

A new study offers the first empirical evidence.

Posted February 15, 2018

I’ve seen the toll that war takes on the human psyche. During the Vietnam War, I was an Army medic working on a psychiatric ward in a military hospital in Georgia. In the psych-jargon of the time, our patients came with an array of impressive sounding diagnoses, the most common being “acute undifferentiated schizophrenia.” In retrospect, I’m pretty sure that many of them were really suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

PTSD is at least as much of problem now as it was back then. Twenty percent or more of the 2.6 million veterans deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan will suffer from PTSD, depression, or a related condition. And veterans have higher suicide rates than individuals who did not serve in the military. While some treatments for PTSD seem to be effective, high drop-out rates from treatment programs are a big problem. Some people believe that providing veterans with trained service dogs would help hundreds of thousands of veterans cope with post-traumatic stress. But are they right?

Uplifting media reports of veterans whose lives are made better by service dogs abound. Aside from anecdotes, however, there has been no solid empirical evidence to support these claims. In a 2015 review of studies of the effectiveness of animal assisted interventions for the treatment of psychological trauma, Dr. Maggie O’Haire of Purdue University found only two studies of military veterans. And even those reports were dodgy. One was a case study on a single veteran, and the other was an unpublished thesis that involved only six subjects.

Enter the Veterans Administration

The evidence that service dogs can improve the lives of veterans is so thin that the Veterans Administration will not pay for these dogs. Their reluctance is understandable as it can cost $20,000 or $30,000 to train a single psychiatric service dog. The VA says it needs evidence that these animals actually help veterans with PTSD, and in 2010, Congress directed them to give it a shot. In 2011, VA researchers initiated a pilot study. Unfortunately, things started going south from the outset. First, the researchers had problems recruiting subjects for the control group. Then dogs bit two children. Finally, several of the dogs developed hip dysplasia, one died from heart disease and another from cancer. In short, the pilot project was a disaster, and it was halted in 2012.

Although their first attempt at a PTSD research project failed, the Veterans Administration is now undertaking a new study which has promise. It is a randomized control trial involving both trained psychiatric service dogs and untrained emotional support dogs. The project is slated to last 18 months, and you can read about it here.

The results of the VA study will not be available for a year or two. But the findings of new study on veterans with service dogs by Maggie O’Haire and Kerri Rodriguez of Purdue University are already in. And the results look promising.

The Purdue Study of Veterans with PTSD

The research involved a collaboration between the Purdue University researchers and K9s for Warriors, a Florida-based non-profit that provides service dogs to military veterans with PTSD. The study involved 141 Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans suffering from PTSD. Seventy-five of the vets were paired with trained service dogs (the dog group) while the other 66 were on the waiting list to get a dog (the wait list group). The vets in the dog group had their dogs for a month to four years. The animals were mostly Labs, Golden Retrievers, and mixed-breed dogs rescued from animal shelters. Like guide dogs for the blind, psychiatric service dog are highly trained to perform specific jobs. These include tasks such as:

- Averting panic attacks.

- Waking patients from nightmares.

- Creating personal space comfort zones in public situations by standing in front of the veteran.

- Reminding patients to take their medications.

Just like the dogs, the veterans also had to be trained. They were required to take an intensive three week course in which they lived in dormitories while they learned how to take care of and handle their new canine partners.

Measuring Psychological Distress

The most important results were based on existing information gathered by K9s for Warriors. The organization requires that individuals getting a service dog and those on the waiting list periodically complete a psychological inventory called the PTSD Check List, a 17-item scale that assesses PTSD symptoms. The scores can range from 17 to 85, and individuals with scores above 50 are diagnosed as having PTSD. Ten-point shifts up or down are considered “clinically meaningful.” This means they have shown substantial improvements or have gotten worse.

At the end of the study, individuals in the dog group and those on the waiting list also took a series of scales designed to assess other aspects of their mental health in addition to the PTSD checklist. These included measures of depression, physical and mental quality of life, satisfaction with life, and their ability to cope with adversity (resilience). The veterans also completed several scales designed to assess their levels of social functioning and their work productivity.

The Good News….

The results of the study are encouraging. Take, for example, PTSD symptoms.

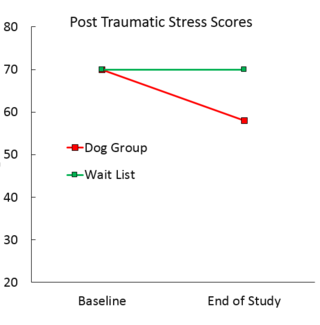

As shown in this graph, when they initially signed up to be paired with a service dog, the veterans in both groups had virtually identical scores on the PTSD symptoms checklist. However, when they took the test at the end of the study, the scores of the dog group had dropped, on average, 12 points. In contrast, the PTSD scores of the individuals on the waiting list had not changed at all.

In addition, the veterans with dogs also were better off than the wait list group in many other ways. The dog group had:

- Lower depression scores

- Better mental quality of life scores

- Greater satisfaction with life

- Higher levels of psychological well-being

- Better abilities to cope with adversity

- Lower social isolation scores

- Greater ability to get out and participate in social activities

The veterans in the dog group also missed work less and show fewer impairments on their jobs. Impressively, many of these differences had, in stat-speak, “large effect sizes.” This means that having a service dog was associated with big differences in the lives of the participants.

What Does It Mean and Where To Go Next?

This research provides the best evidence we have that psychiatric service dogs may reduce PTSD in veterans. O’Haire and Rodriguez, however, are careful not to make exaggerated claims about their results. They point out, for example, that while the PTSD Check List scores of the dog group dropped a “clinically significant” 12 points, the veterans in the dog group were not “cured.” Their scores, on average, remained above 50 on the PTSD Check List.

Indeed, the researchers regard their efforts as a pilot study, and in their article, they discussed some of the limitations of their research. Among these are the lack of random assignment of veterans to conditions, the fact that the changes observed in PTSD symptoms could be due to maturation rather than the presence of the dogs, the reliance on self-reports, and the lack of a true control group. Finally, as Kerri Rodriguez pointed out to me in an e-mail, the degree their findings would apply to the average military veteran is unclear because their sample is biased towards individuals who wanted a service dog.

O’Haire and Rodriguez consider this research a preliminary study demonstrating that it is possible that service dogs can ameliorate the symptoms of PTSD. What we need, of course, is a prospective clinical trial in which some veterans suffering from PTSD are assigned to a service dog group and others to a control group. The study would need to have sufficient “statistical power” (enough subjects) and, ideally, long-term follow ups. Such a study would, of course, take time, effort, and, most importantly, money. The good news is that, based on these preliminary results, the Purdue researchers were able to convince the National Institutes of Health to provide funds for a clinical trial. Their study is currently underway with the results expected in 2019.

I’ve got my fingers crossed.

For more information on Dr. O'Haire's research on PTSD, click here.

And click here to read about her studies on the impact of Guinea pigs on the behavior of children with autism.

References

O'Haire, M. E., & Rodriguez, K. E. (2018). Preliminary efficacy of service dogs as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military members and veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(2), 179-188.

Saunders, G. H., Biswas, K., Serpi, T., McGovern, S., Groer, S., Stock, E. M., ... & McCranie, M. (2017). Design and challenges for a randomized, multi-site clinical trial comparing the use of service dogs and emotional support dogs in Veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Contemporary Clinical Trials, 62, 105-113.