Relationships

Gulls: Our Love-Hate Relationships with Raucous Neighbors

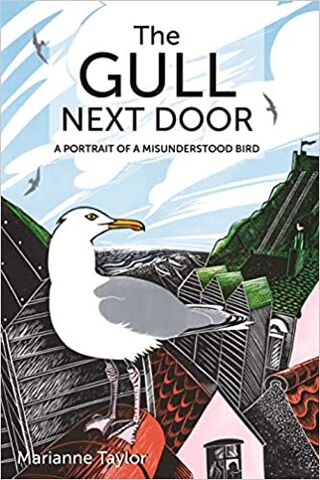

An interview with gull enthusiast Marianne Taylor about these remarkable birds.

Posted October 1, 2020

"The Gull Next Door reveals deeper truths about these remarkable birds. They are thinkers and innovators, devoted partners and parents. They lead long lives and often indulge their powerful drive to explore and travel. But for all these natural gifts, many gull species are struggling to survive in the wild places they naturally inhabit, which is why they are now exploiting the opportunities of human habitats. This book shows how we might live more harmoniously with these majestic yet misunderstood birds."

"I ask readers to continue to enjoy and support their local ecosystem in all its messy glory, and to make friends with the gull next door." –Marianne Taylor

I've long been fascinated by gulls, and as an ethologist, was first introduced to these remarkable birds by reading–and rereading countless times–Nobel laureate Niko Tinbergen's classic The Herring Gull's World: A Study of Social Behavior of Birds. So, I was thrilled to learn of a new book by gull lover–a truly dedicated larophile–Marianne Taylor, and pleased she could take the time to answer a few questions about her information-packed book The Gull Next Door: A Portrait of a Misunderstood Bird.1

Our love-hate relationships with gulls made me think that they also can also serve as warning signs–"canaries in the coal mine"–and tell us a good deal about our complicated and destructive relationships with a host of urban animals with whom we share various environs and how we need to change our ways to foster peaceful coexistence. Here's what Ms. Taylor had to say about these remarkable birds.

Marc Bekoff: Why did you write The Gull Next Door?

Marianne Taylor: Gulls are much maligned, but they have always been favourites of mine—in part for the very reasons that so many people dislike them. With wildlife and wild places vanishing fast in the face of relentless human expansion, I find both joy and hope from observing those wild animals that have learned to live alongside us, and even manage to exploit our way of life to drive their own survival. I wrote this book with the hope of inspiring the same feelings in others, through revealing the true beauty, braininess, and brilliance of these birds and their relatives, and I loved having the opportunity to relate some of the many joyful moments I’ve spent in the company of gulls

MB: How does your book relate to your background and general areas of interest?

MT: Herring gulls were my boisterous, noisy, and endlessly watchable neighbours throughout my childhood. As I got older and my interest in nature grew, I travelled further to see more birds. I became familiar with other gull species and came to love them all, in their diversity of form and lifestyle. I also learned of the array of threats they face, and that even my local herring gulls were fast-declining in the wider countryside—only their (relatively small) urban populations were doing well. I came to see seaside-dwellers like myself as guardians of the gulls, and to grow increasingly puzzled and frustrated by the hostility directed at them by some people.

I studied psychology at university and specialised in animal behaviour, and after graduating, I worked for a publisher of bird books. One of the titles we produced was Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America, a tremendous 608-page tome devoted to gull identification, and this served as my introduction to the world of "larophiles"—birdwatchers with a particular (some would say obsessive) interest in gull-watching. With their bewildering and highly variable array of plumages, the large gulls, in particular, can be extremely difficult to identify, and a particular type of person is captivated by this challenge. When I became a writer, I knew I wanted someday to write about gulls but also about gulls and people—to understand both larophobes and larophiles.

MB: Who is your intended audience?

MT: This book is for birdwatchers and nature-lovers, those who live among gulls by the sea and those who (like me until recently) don’t currently live by the sea but feel a bone-deep yearning for it every time they hear the cry of a gull overhead. It’s for every day-tripper who has had a chip swiped right out of their hand by a ninja-sneaky herring gull, and everyone who likes to spend hours staring at a rubbish tip trying to find the one rare vagrant gull among thousands of commonplace ones.

MB: What are some of the topics you weave into your piece and what are some of your major messages?

MT: I explore the natural history of gulls—their evolution, diversity, and modern ways of life. In particular, I look at their adaptability and intelligence, the traits that enable (some of) them to live and thrive alongside humans in a world that is changing so much and so fast. I explore their history as victims of exploitation, the conservation challenges they present today, and their possible futures. Throughout the book, I draw on personal experience of time with gulls and time with people who love (and hate) them. I also spend some time diving into the strange world of the UK’s local newspapers and their often comedically lurid gull-themed headlines—I explore and in some cases debunk the more outrageous examples.

In nearly every town and city around the world, you’ll find a small cohort of smart and adaptable wild animals living in whatever space remains between all the "human stuff," and often these animals are hated, simply because we are sometimes a little inconvenienced by their activities. Depending where you live, it may be foxes, raccoons, rats, crows, ibises, or pigeons—though often they are known by derogatory nicknames (raccoons are "trash pandas," ibises are "bin chickens"). In my childhood home town it is herring gulls—aka "sh*tehawks," "rats-with-wings," and other unflattering epithets. They are vilified simply for trying to live.

I want my readers to understand that gulls are not our enemies and we don’t need to be theirs, that those of us who live alongside them can find ways to do so in harmony. I make no bones that some gull behaviours can be annoying for us (and I talk about the times I’ve experienced their less pleasant side) but I appeal for tolerance, and a wider view to what our gulls are telling us about the health of both wild coastal and marine habitats, as well as the value of nature for our own wellbeing, even within our most urban environments.

MB: How does your book differ from others that are concerned with gulls and some of the same general topics?

MT: There are quite a few identification guides to gulls on the market, including some real masterpieces of the genre. This is the only narrative celebration of gull-kind that I’m aware of, though. Like similar books focusing on other animal groups, it is highly personal, but its largely urban settings are unusual among nature writing.

MB: What are some of your current projects?

MT: I’m working on quite a variety of writing projects at present, covering themes from wildlife in the Bible to the anatomy of trees. I spend as much of my free time as possible swimming in the sea, a rekindled childhood passion which is bringing me closer to wildlife in a new way. This is something I hope to bring into my writing over the coming months and years, unless I get eaten by a shark.

MB: Is there anything else you'd like to tell readers?

MT: I would just like to urge everyone to stop and look more closely at wildlife in general but urban wildlife in particular. On a fundamental level, we need a healthy natural world if our own species is to survive—a hard but inescapable lesson. It isn’t just about the air we breathe and the food we eat, though—it’s becoming increasingly well-evidenced that seeing and experiencing wildlife every day has untold benefits for our mental health. The worldwide lockdowns we’ve experienced as a consequence of COVID-19 have inspired a new surge of appreciation for our close-to-home wildlife in particular, and the emergence of COVID-19 has itself underlined the importance of respecting the natural world. So I would ask readers to continue to enjoy and support their local ecosystem in all its messy glory, and to make friends with the gull next door.

References

1) Marianne Taylor is a freelance writer, illustrator, photographer, editor, and the author of more than thirty natural history books, including Dragonflight, Tracking the Highland Tiger, and The Way of the Hare. A passion for all wildlife has always been a driving force in her life. Growing up in the English seaside town of Hastings instilled in her a deep love of coastal and marine wildlife, and in particular a fondness for the herring gulls who built their own town on the Hastings rooftops.

Bekoff, Marc. Neighborly Animals Offer Valuable Lessons About Coexistence.