Career

A Better Way to Think About Work-Life Balance

Work-life balance is about making decisions about our personal resources.

Posted March 30, 2021 Reviewed by Chloe Williams

Key points

- Most definitions of work-life balance reflect the degree to which people allocate their resources effectively across their work and non-work lives.

- The Personal Resource Allocation framework assumes that we have one pool of resources that we use to respond to demands in all domains of life.

- When the demands we face, the resources we have, and our perception of the sufficiency of those resources are aligned, we have greater wellbeing.

- Some ways to improve work-life balance include noticing negative feelings about life demands and finding ways to reduce demands or increase time and energy.

Work-life balance is a term that never seems to reach its expiration date, and it receives an enormous amount of coverage. A quick Google search using “work-life balance” (including the quotes, so it is a more restrictive search) results in over 67 million hits. Obviously, it is a topic that has broad interest.

A recent article by Lufkin (2021) was one of the latest in the popular press to delve into this issue. The article contended that it’s a mistake to approach work-life balance as a goal to be achieved. Instead, Lufkin somewhat reframed the issue as a function of the decisions we make about our limited personal resources. Here, I want to discuss personal resources more fully in the context of work-life balance.

Understanding Work-Life Balance

What exactly is work-life balance? Back in 2015, I pointed out several of the inherent issues with this term, including that people vary tremendously in terms of how they define it[1]. Differing definitions come with different assumptions as well. Defining work-life balance as a clear separation between work and life implies that people should seek out ways of segmenting their work life from their non-work life. Defining work-life balance as feeling in control of one’s life doesn’t assume work and life must be segmented and instead assumes that as long as people feel in control, they are experiencing work-life balance.

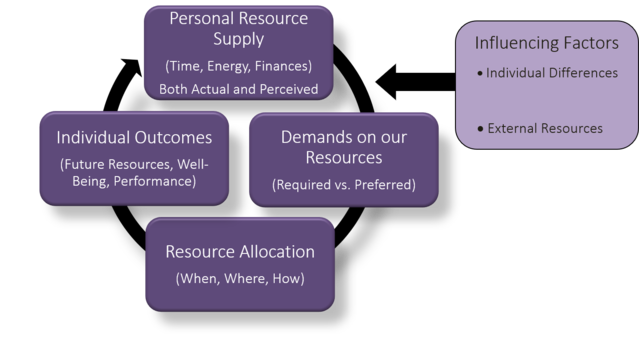

Even in the scholarly literature, there isn’t an agreed-upon definition[2], meaning that most people are on their own for determining what work-life balance means. Since people have their own implicit understanding of what it is (or isn’t), how they go about pursuing it also varies. However, most of these implicit ways of defining work-life balance come down to the degree to which people allocate their resources effectively across their work and non-work lives[3]. This is why I take a personal resource allocation (PRA) approach to this topic[4], which I discussed as it applied to the current pandemic (see also Figure 1, for a visual of the PRA process).

The Personal Resource Allocation Framework

The PRA framework is built on two assumptions. The first assumption is that work and non-work are both part of the overarching life domain. We have one limited pool of available resources that we use to respond to demands across all domains of our lives.

The second assumption is that there isn’t a right way to allocate resources. Instead, what is of most relevance is the alignment between (1) the demands we face, (2) the resources we have at our disposal, and (3) our perception of the sufficiency of those resources. When these three elements are aligned, we tend to experience relative success and more positive wellbeing, but when they are misaligned, we tend to experience difficulty in meeting demands and more negative wellbeing.

Implications of the PRA Framework for Resource Allocation

When considering Figure 1 and the assumptions of the PRA framework, a variety of implications for our work-life interface become evident.

Perhaps the most obvious implication is that personal resources are limited. We have a finite amount of time, energy, and financial resources available at any time; and we make choices about where, when, and how to allocate those resources. Although all personal resources can be replenished[5], we can only expand our energy (e.g., via exercise, good nutrition) and financial (e.g., pay raises, new income sources) resources[6].

Additionally, any activity toward which we want to or have to allocate personal resources is a demand[7]. We’re generally more willing to allocate personal resources toward demands we prefer or desire (things we want to do) than toward demands based strictly on obligation or requirement (things we have to do). Because they pull from the same pool of resources, we benefit when we manage both types of demands.

Another implication is that personal resources are interdependent. This is evident in several ways, including:

- Time and energy are both required for most demands[8].

- Time and energy are both generally required to create or expand financial resources.

- Financial resources can be allocated to conserve time and energy[9].

- Time can be allocated to activities that replenish or expand energy (i.e., sleep, eating, exercise).

Finally, idiosyncratic factors often influence resource allocation. Influencing factors impact our successful management of personal resources in various situations. For example, highly extraverted people may find social demands less effortful than highly introverted people, and people vary in the external resources (e.g., social support, technology, workplace resources) on which they can rely to help manage their demands[10].

Making Decisions to Improve Your Work-Life Interface

I tried to make sense of Lufkin’s five-step process, and I referred to the referenced Lupu and Ruiz-Castro (2021) article, but the steps discussed didn’t seem to fit together into an actual process. So, instead, I thought here I might offer some very practical suggestions for how to improve misaligned aspects of your personal resource allocation. I should note, however, that these are intended to be more diagnostic suggestions as opposed to a specific roadmap for improvement[11].

1. Be attentive to when things aren’t working. Experiencing anxiety, frustration, tiredness, or irritation about life demands – especially when consistently recurring – is a sign that your personal resources are misaligned with your demands.

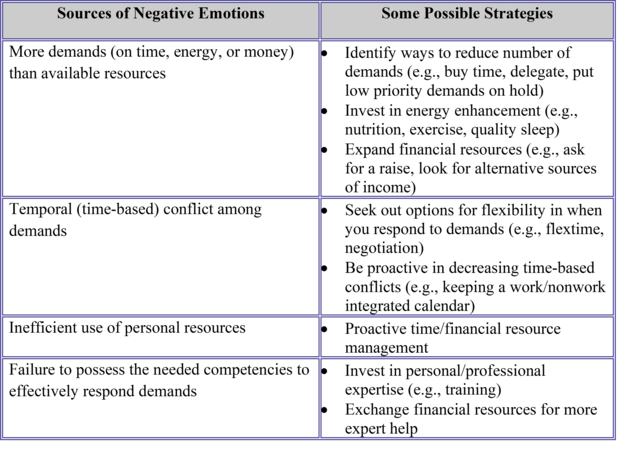

2. Identify the source(s) of those negative emotions. Many PRA-related negative emotions likely stem from one or more of the following sources:

- More demands (on time, energy, or money) than available resources;

- Temporal (time-based) conflict among demands;

- Inefficient use of personal resources; and

- Failure to possess the needed competencies to effectively manage demands.

3. Consider potential options for expanding your personal resources or how you manage your existing resources. You should identify some possible options for improvement. If the primary source is a demand-resource imbalance, you could consider how to reduce the number of demands (e.g., delegating, putting lower priority demands on hold) or how to expand energy (e.g., better sleep, getting more regular exercise) or financial (e.g., ask for a raise, seek out additional sources of income) resources (see Table 1 for some possible strategies).

4. Implement some changes. It is possible you identify several ways to enhance your personal resource allocation. However, it’s important to not try to do too much at one time. Instead, identify what you consider to be one to two high-leverage changes to make and focus on those. Once they’re implemented and a part of your routine, you can re-assess your overall resource allocation satisfaction.

Footnotes:

[1] Or at least what they mean when they use the term.

[2] Kalliath and Bough (2008) identified six different conceptualizations of work-life balance within the literature.

[3] I will also note here that I dislike the term work-life balance and instead prefer the term work-life interface because it isn’t focused as much on separating work and life but examining the (in)compatibilities between the two broad life domains.

[4] Grawitch, Barber, and Justice (2010) specifically defined work-life balance as “effective personal resource allocation across all life pursuits” (p. 130).

[5] Each day gives us another 24 hours, sleep and nutrition replenish energy, and regularly paychecks replenish financial resources.

[6] Time cannot be expanded, as there is no way to objectively increase the number of hours in a day.

[7] Demand is often used to describe negative pressures on us, but that wouldn’t be an accurate description because it ignores all the activities and tasks in life toward which we choose to allocate time, energy, or money. These want-to activities still demand time, energy, or money, the same as required demands.

[8] Time and energy are highly co-mingled. However, this relationship is not perfectly linear as some demands can be very effortful but not time-consuming and other demands may be very time-consuming but not effortful.

[9] This is what is commonly referred to as buying time.

[10] External resources are seldom free but, instead, allow you to exchange some existing resources for more in-demand current or future resources. Social support, for example, often results from the prior allocation of time and energy to social relationships, whereas buying time (e.g., grocery delivery service) may offer a more real-time exchange of financial resources to protect time or energy resources.

[11] Due to the idiosyncratic nature of PRA.