Transference

Transference is a phenomenon in which one seems to direct feelings or desires related to an important figure in one’s life—such as a parent—toward someone who is not that person. In the context of psychoanalysis and related forms of therapy, a patient is thought to demonstrate transference when expressing feelings toward the therapist that appear to be based on the patient’s past feelings about someone else.

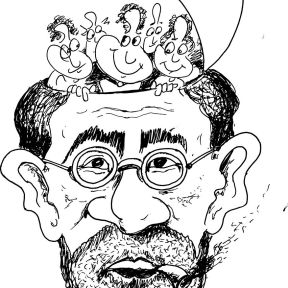

The concept of transference emerged from Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic practice in the 1890s. Freud believed that childhood experiences and internal conflicts formed the foundation for one’s development and personality as an adult. Psychoanalysis aims to uncover those unconscious conflicts—which may be responsible for current patterns of emotion and behavior. Transference is one method through which those conflicts may be recognized and, hopefully, resolved.

If a patient’s mother was extremely judgmental to her as a child, and the therapist makes an observation that the patient perceives as judgmental, the patient might express that and even lash out at the therapist. This response could be interpreted as her applying to her therapist the same feelings that she felt toward her mother. A patient’s response to a therapist may also resemble her response to a romantic partner or some other person in her life.

Psychologists argue that transference occurs in everyday life, even if it’s more closely examined in certain forms of therapy. For example, a woman could feel overly protective of a younger friend who reminds her of her baby sister. A young employee might experience the same sort of feelings he has about his father when in the presence of a boss who resembles the father in some way.

The repetition of emotional responses to one individual (such as a parent) in the context of a different relationship is theorized to take place without conscious awareness. However, a person can become consciously aware of this pattern. Indeed, drawing attention to and seeking to interpret the transference exhibited by a patient is one goal of psychoanalysis and psychodynamic therapy.

In transference, someone may be described as “projecting” feelings from past relationships onto the therapist in the present. But there is also a distinct concept of projection—also associated with Freud and psychoanalysis—that means attributing one’s own characteristics or feelings to another person. In transference, one’s past feelings toward someone else are felt toward a different person in the present.

While much of Freud’s framework has proven difficult to validate empirically, his theories spurred the growth of psychology, and a number of his ideas—including transference—remain relevant to therapists today. Especially in psychoanalysis and psychodynamic forms of psychotherapy, transference is considered a useful therapeutic tool.

In therapy, both positively and negatively shaded kinds of transference may occur. “Idealized transference” describes when a patient assumes that the therapist has certain positive characteristics (such as wisdom). If the positive feelings are not too exaggerated, this form of transference may be useful for the therapist-patient alliance. Negative transference might be at work when a patient has feelings about the therapist, such as suspicion or anger, that seem to be based on experiences from past relationships.

A patient’s experience of sexual or romantic feelings about the therapist has been called sexualized transference. The concept dates back to Freud, who posited that some patients fall in love with their therapist because of the context of psychoanalysis, not because of the actual characteristics of the therapist. Later theorists distinguished between “erotic transference,” which can involve sexual fantasies that a patient realizes are unrealistic, and “eroticized transference”—a more intense and problematic pattern that may include explicit sexual overtures from a patient.

Many therapists consider transference and its interpretation to be a therapeutic opportunity. By bringing attention to a relational dynamic—such as a tendency to feel disproportionately angry or anxious in certain kinds of interactions—a therapist can try to help a patient understand and address patterns that might contribute to problems outside of therapy. However, in some cases, such as when a patient shows hostility toward the therapist, or overt sexual interest, transference may pose a threat to the therapeutic relationship that needs to be managed.

When a therapist recognizes that transference is occurring, it can be an opportunity to identify an underlying problem to address and resolve. Raising the issue could provide something of an “aha moment” to patients who may not have been able to spot the problematic pattern before. But pointing this out isn’t easy—it may upset the client or prevent them from opening up. The therapist would likely consider the relationship they have with the client, the level of trust the two have built, and whether the time is right when deciding whether to call out transference.

Countertransference refers to a therapist’s reactions to a patient, including a therapist’s emotional responses to a patient’s feelings. As when a patient seems to “transfer” feelings about someone else to the therapist, the therapist may have certain feelings about the patient—annoyance, perhaps—that might be partly linked to irrelevant factors, such as the patient’s resemblance to another (annoying) person.

Directing feelings of attraction, anger, or other emotions toward a patient can provide insight or potentially harm the relationship, so it can benefit therapists (and patients) to be aware of the phenomenon and address it if necessary. Therapists who determine that their emotional response to a patient may hinder their ability to work with them objectively may adjust accordingly. A therapist may also use observations of their feelings about a patient to make inferences about how other people might feel about the patient.

The idea of the therapist as a “blank screen” or “mirror” is traditionally considered important in psychoanalytic therapy: In short, the therapist seeks to remain somewhat anonymous to the patient. The aim is to allow aspects of the patient’s unconscious to come to light in the interactions with the therapist—including through transference, which is theorized to be more likely when a therapist does not reveal too much about themselves.