Repression

Repression is a defense mechanism in which people push difficult or unacceptable thoughts out of conscious awareness.

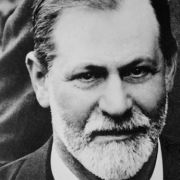

Repressed memories were a cornerstone of Freud’s psychoanalytic framework. He believed that people repressed memories that were too difficult to confront, particularly traumatic memories, and expelled them from conscious thought.

This idea launched an enduring controversy in the field of psychology. The notion that people repress traumatic memories that can be recovered in therapy has been discredited. There is ample evidence that people remember traumatic experiences—even if they wish they could forget them—and that memory is more malleable than previously believed.

Outside of the repressed memory debate, people may refer to repression colloquially, describing the tendency to push difficult feelings down or avoid confronting certain emotions or beliefs.

Freud conceived of repression as the root of people’s “neuroses,” the term he ascribed to mental struggles such as stress, anxiety, and depression. These patients could be treated, he believed, by recalling repressed experiences into consciousness and confronting them in therapy. This led to a sudden and dramatic outpouring of emotion, dubbed catharsis, and the attainment of insight.

In the course of treatment, the patient might show resistance by changing the topic, blanking out, falling asleep, arriving late, or missing appointments. Freud believed that such behavior suggested that the patient was close to recalling repressed experiences but was still afraid to do so.

Although these ideas have largely been disproven, Freud’s ideas about the unconscious and defense mechanisms helped shape the field of psychology.

Freud believed that repressed material, though unconscious, was still present and could resurface in disturbing forms. As well as a lack of insight and understanding, the inability to process and come to terms with repressed material could lead to psychological problems such as poor concentration, irritability, anxiety, insomnia, nightmares, and depression. He believed that maladaptive and destructive patterns of behavior such as anger and aggression could emerge due to reminders of the repressed material.

Suppression is similar to repression but with one key difference—forgetting is conscious rather than unconscious. Suppression refers to the conscious and sometimes rational decision to put an uncomfortable (although not totally unacceptable) stimulus to the side, either to deal with it at a later time or to abandon it altogether. Suppression can be viewed as a conscious analog of repression.

Repression is often confused with another defense mechanism, denial, in which people refuse to admit to certain unacceptable or unmanageable aspects of reality, even in the face of evidence to the contrary. Denial involves a refusal to admit the truth while repression involves unconscious “forgetting.” Nonetheless, denial and repression often work together and may be difficult to disentangle.

Sexual repression is when the ability to express sexuality is thwarted, which can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, frustration, and anger. The distorted rage resulting from sexual repression is often directed at helpless victims rather than the people and institutions—such as religious institutions or medical figures—that champion ideas of sexual repression.

The notion of repressed memories has generated tremendous controversy, which largely came to a head in the 1990s. The belief that traumatic memories were repressed and that psychologists could restore them led to “recovered memory therapy,” in which therapists used dubious techniques to reconstruct traumatic memories, often of childhood sexual abuse. (Recovered memories are distinct from dissociation, a common response to sexual abuse in childhood.)

However, the techniques involved often manipulated people’s memories instead of “uncovering” true ones, and they even hurt patients’ mental health. The work of psychologist Elizabeth Loftus and others has demonstrated that memory can be malleable and that it’s susceptible to manipulation.

Although the concept of recovered memory has been discredited, many therapists and patients still believe that the phenomenon is possible.

Research does not support the existence of repressed traumatic memories that can be recovered. Events of people’s past may sometimes come back to them in sudden recollection, but there’s no evidence that this happens with traumatic memories. Indeed, prospective research (following people after a traumatic event) finds that trauma victims often want to forget their experiences, but they cannot.

Research also reveals that memory itself is far less reliable, and much more flexible, than commonly believed. The techniques therapists used to “recover” memories also worked to implant false memories and create realistic, recalled experiences of events that never happened.

Memories are not always accurate—they are often sensory and emotional impressions blurred by imagination, belief, ambiguity, and time.

For example, participants in a study read a story about a man who walked out of a restaurant without paying. Half the participants were told that he "was a jerk who liked to steal" and half were told that he had received an emergency phone call. A week later, the people who were told that the man was a jerk remembered the bill being higher than it was, and those who were told he received an emergency phone call remembered the bill being lower than it was. In another experiment, researchers showed volunteers images and asked them to imagine other images at the same time. Later, many of the volunteers recalled the imagined images as real.

Research suggests that false memories may emerge because people might associate thoughts with something positive or negative—there could be a false association of what people have in their minds rather than what actually happened to them.

Research finds that widespread belief in repressed traumatic memories persists among therapists. Between 60 and 89 percent of mental health clinicians believe that traumatic memories can be forgotten, repressed, or suppressed. A study of clinicians who utilize Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) to treat trauma, also a controversial practice, found that 93 percent of these clinicians believed that traumatic memories can be “blocked out.”

A large portion of the general public, between 40 and 89 percent, believe that traumatic memories can be repressed and forgotten, and that even an act of murder can be suppressed.

The controversy and confusion surrounding repressed memories in the mental health field has permeated the court system. Many criminal cases have been based on witnesses' testimony of recovered repressed memories, often of alleged childhood sexual abuse. In some jurisdictions, the statute of limitations for child abuse cases has even been extended to accommodate the phenomena of repressed memories as well as other factors. On the other end of the spectrum, courts have rejected false memories as evidence, deeming it inadmissible due to lack of reliability, a viewpoint that has been shaped by testimony from Elizabeth Loftus and others.