Law and Crime

Can We Predict Crime Using Brain Scans?

Brain activation during impulse control may forecast criminal behavior.

Posted April 17, 2013

In 1968, Rodney Alcala lured an 8 year old girl into his apartment where he raped and attempted to murder her before police knocked on his door and he fled. He was later arrested, convicted of assault and sentenced to prison. After a short prison term, he was paroled in 1974. In the next five years, he went on to kill at least 5 young women, perhaps many more. If the criminal justice system could have known that he would become a serial killer, would he have still been released?

Such a prediction may sound like science fiction, but a study out this past month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that forecasting future criminal behavior could become reality in the near future. This study offers the first evidence that brain scans might be used to predict who will commit a crime.

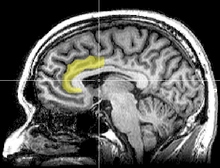

Activity in a region called the anterior cingulate cortex helped determine not only which prisoner’s were most likely to commit a crime upon release from prison, but also how long it would take before the prisoner’s broke the law.

The study was led by postdoctoral scientist Eyal Aharoni, working at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Eyal worked with cognitive scientist Michael Gazzaniga and Kent Kiehl, a leading expert on architectural changes in the brain that may underlie psychopathic behavior (he also grew up near Ted Bundy).

Ninety-six male prisoners completed an MRI scan before they were released from prison on parole or probation. During the scan, they performed a task designed to measure impulsive behavior. Called go/no-go, the object of the task is to watch a screen and press a button when an ‘X’ appeared (a ‘go’ trial), but not when a ‘K’ appeared (a ‘no-go’ trial). To make the task challenging, participants had to press the button in less than a second for it to count. ‘X’ appeared on 84-percent of trials, priming participants to press quickly and fall into a rhythm. When a ‘K’ popped up, they had to stop themselves from pressing the button.

Anterior cingulate cortex

Impulsive people have a more difficult time preventing themselves from pressing a ‘K’ so they make more errors than the average person. Kiehl has shown that criminals often press the button even when a ‘K’ shows up, providing evidence that criminals are more impulsive than average. The part of their brain responsible for stopping an action may be deficient. In terms of crimes, once they get started on an action, even if they realize potential negative consequences, they cannot stop themselves.

Soon after finishing the study, the prisoners were released. Eyal kept tabs on them using criminal background checks for the next 3 years. During those three years, 53 percent committed a crime and were arrested. 44 percent committed non-violent crimes and 9 percent committed violent crimes.

Eyal then looked at the brain activation of the prisoners that was recorded before their release. He focused on the anterior cingulate cortex because of previous studies showed it was more active when healthy volunteers tried to withhold a response during the go/no-go task. He found that the prisoners with the least activation in the anterior cingulate cortex during the task were most likely to commit a crime in the three years after being released. Further, the level of brain activation predicted how long it would take before the person committed the crime.

Based on this information, the authors concluded that brain activation in the anterior cingulate cortex may forecast an individual’s likelihood of committing a crime in the future. Although previous studies had shown differences between criminals’ brains and comparison volunteers during impulse control, there was no direct evidence that these differences were directly linked to criminal tendencies—it could be correlation, not causation. Since this study showed differences in brain activation prior to arrests, it suggests that how a person’s brain processes impulse control might be important in their risk for committing crimes.

One question that the study left unanswered was exactly how diminished anterior cingulate cortex activation might contribute to criminal behavior. Activity during an impulse control task could reflect a number of processes. The anterior cingulate cortex has also been implicated in error monitoring the likelihood of making an error. ‘K’ appeared 16-percent of the time, so it's possible that anterior cingulate cortex activity during the task was related to calculating when an error was likely. Determining which process underlies the different anterior cingulate cortex activation would be important, because each may require different therapies.

At this point, it remains to be seen whether neuroimaging predictions can be replicated (see Russ Poldrack's analysis). As with many prediction models, the better they fit the specific data, the less likely they are to extend to a new group. Although this study used a specific region of the anterior cingulate cortex, this specific region may not be useful in another group or even in the same group if a different task was used to measure behavior.

The authors discuss some possible ethical implications in their article (they even brought an ethicist in as an author of the study, something unusual for neuroscience research). They suggest that the technique would have to be refined and its accuracy validated in larger studies before even considering its use in sentencing convicted criminals. Even if not used in the courtroom, however, predictions could be used to determine which criminals need the most therapy to rehabilitate them.

Regardless of how information about a criminal’s risk for future crime is used, it’s necessary that we better understand the specifics before we make any conclusions. But when you read about a criminal like Rodney Alcala, who received a short prison sentence for his first crime, it’s easy to wish we had kept him behind bars in 1974. If we were able to anticipate his violence, we might have prevented it.

Image credit: Arenamontanus

Reference: Aharoni E, Vincent GM, Harenski CL, Calhoun VD, Sinnott-Armstrong W, Gazzaniga MS, Kiehl KA. Neuroprediction of future rearrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Apr 9;110(15):6223-8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219302110. Epub 2013 Mar 27. PMID: 23536303.