Attention

Value Also Drives Attention

Three key factors affect what we notice in the world.

Posted July 22, 2019

There is a massive amount of information in the world (not to mention a huge amount of information stored in people’s brains). Psychologists use the word attention to refer to the mechanisms people have to cut down on the amount of information being used at any given moment to a manageable amount.

For example, visual attention involves choosing which objects in the world people will fixate on and what aspects of those objects are important. For a long time, the focus of research in this area was on the contributions of two factors in visual attention.

One factor is the visual importance of particular features of the visual environment. For example, a flashing light will attract attention, which is one reason why flashing lights are often used as parts of warning systems. Dim lights tend not to attract attention (and are typically not used as parts of warning systems).

The second factor involves people’s goals. Attention is often grabbed by objects that are important to you because you need them for some purpose. If you have misplaced your keys, then as you walk through your house, your attention will be drawn to small objects that look like your keys, even though you might not notice your keys if you didn’t need them at that moment.

Over the past decade, research has highlighted a third key determinant of visual attention—value. When an object (or even a feature of an object) comes to have value for a person, then it will attract attention regardless of the overall salience of that feature or the relevance of that feature to a particular goal.

One early demonstration of this phenomenon came from a paper by Brian Anderson, Patryk Laurent, and Steven Yantis in the June 2011 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

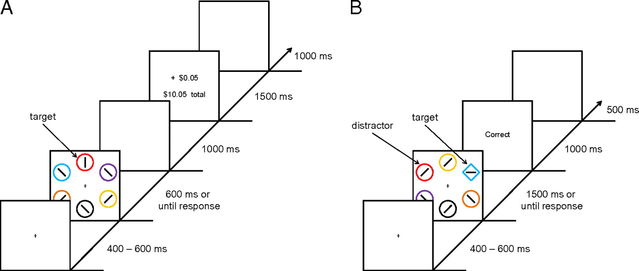

To give a particular stimulus value, participants first did a simple search task. On each trial of this task, six circles appeared on the screen. Inside each circle was a line segment that was either vertical or horizontal. Participants were told to search for a red or a green circle. On each trial, there would be one red or one green circle. Then, they pressed one button if the line segment in that circle was horizontal and a different button if was vertical. If the participant responded correctly, they received either one cent or five cents. For example, for some participants the color red was high-value, and so most correct responses to the line segments inside red circles got a five-cent reward.

To give the colors red and green different values, one color was randomly selected so that a correct response for line segments in a circle of that color were generally given the five-cent reward, while responses to line segments inside circles of the other color were generally given the one-cent rewards. Participants were not told about this difference.

The idea behind this first part of the study is that over the course of over 1,000 training trials, participants would gradually learn that one color was associated with a higher reward than the other.

After the training phase was complete, participants did a second task in which six shapes were presented on the screen. Five of them were circles, and one was a diamond. Once again, there were line segments inside each shape, and participants had to identify whether the line segment inside the target shape was vertical or horizontal. Participants had to identify the orientation as quickly as possible, and the experimenters measured how long it took people to respond.

Each shape had a color. In some trials, one of the circles was red or green (the two colors used in the first phase of the study). The diamond (which was the target shape for this part of the study) was never red or green.

The prediction for this study is that if valuable things in the visual environment attract attention, then on trials where one of the circles has the high-value color, it should attract attention away from trying to find the target shape. So, on those trials, people should be slower to respond to the orientation of the line in the target shape than on trials where there is a circle with the low-value color. The trials where none of the circles were red or green served as a baseline.

Consistent with the idea that valuable items attract attention, when one of the circles in the array was the high-value color, participants responded more slowly than when one of the circles was the low-value color or when none of the circles were red or green. The low-value color did not slow people down compared to the trials where none of the circles were red or green. So, even though the color of the circle is completely irrelevant for solving the task in the second phase of the study, the high-value color continued to attract people’s attention.

Over the years since this study was first done, it has been replicated many times, and psychologists have also begun to explore the brain regions associated with this effect. As a result, we now believe that salience, goals, and also value influence what people pay attention to in the environment.

References

Anderson, B.A., Laurent, P.A., & Yantis, S.(2011) Value-driven attentional capture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(25), 10367-10371.