Neuroscience

Mind-Melding With Our Favorite Fictional Characters

Brain research explores how we become like-minded with fictional characters.

Posted April 19, 2021 Reviewed by Matt Huston

Key points

- Identifying with a character in a work of fiction can make us think like that character, even after we've closed the book or turned off the TV.

- A study suggests that habitual identification with fictional characters is associated with differences in brain activity.

- Many of us may use the same "neural machinery" to think about characters we identify with that we use to think about ourselves.

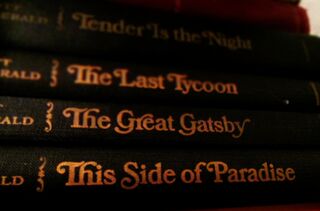

While I was enduring a bout with COVID back in February, I found an old copy of The Great Gatsby on the bookshelf of my basement quarantine refuge and read it again for the first time in many years. The hopeless idealism of Jay Gatsby and the destructive materialism of Tom and Daisy Buchanan have always fascinated me, but what I found most appealing on this recent reading—as in all of my earlier ones—was the persona of the novel’s narrator, Nick Carraway. I have always identified with Nick’s inclination “to reserve all judgements,” and sympathized with his observation that while such a temperament opens one up to “many curious natures,” it just as frequently makes one “the victim of not a few veteran bores.”

A couple of weeks after I emerged from the basement and resumed my place in human society, I was standing in line at the pharmacy in Walmart when, after the exchange of a few generic comments about the weather, the man standing behind me launched into a lengthy monologue about gardening and his vast and varied experience with growing vegetables in a mountain climate. I nodded politely and listened to the story, but in my head I was longing for escape, and it was Nick Carraway’s voice that gave shape to this inchoate longing: “frequently I have feigned sleep,” Nick’s voice said in my inner ear, “preoccupation, or a hostile levity when I realized by some unmistakable sign that an intimate revelation was quivering on the horizon.”

As the pharmacist called “Next please” and waved me over to the counter, it occurred to me that I had once again filtered a real-life personal experience through the point of view of a fictional character, as I have been known to do. A recent study suggests that this impression I sometimes have that I am thinking with the mind of a character who exists only in a work of fiction is more than just a figment of my imagination.

The Study: Fictional Characters on the Brain

Seeking to find out what sort of brain activity is involved in our personal identification with fictional characters, researchers at The Ohio State University recruited 19 self-professed Game of Thrones fans to perform trait evaluations of nine characters from the HBO series, nine real-world friends, and the self during functional neuroimaging. Given that introspection about the self is associated with increased activity in the brain's ventral medial prefrontal cortex, the researchers were looking for neural overlap in this region between the self and fictional characters, as compared with the self and real-world friends.

Prior to the study, participants completed a survey to determine the level of connection they felt to the targets of the trait evaluations they would be performing, rating the nine Game of Thrones characters and their nine real-world friends on “familiarity, closeness, similarity to self, and liking.” Then, while they were in the scanner, the participants completed trait evaluations of the fictional characters, their friends, and the self. Presented with a series of two words arranged vertically—the name of a fictional character, the name of a friend, or the word "self" on top, and one of 36 valence-based trait adjectives on the bottom—they responded “yes” or “no” according to how accurately the adjective described the target.

From the imaging data produced during the trait evaluations, neural responses were extracted for “Self, Friends, and Fictional Characters” from a region of the ventral medial prefrontal cortex that had previously been identified as showing a greater response during self-referential as opposed to other-referential judgements. Following the trait evaluation task in the scanner, the participants completed a personality inventory that included a Fantasy subscale, indicating the tendency to “transpose [oneself] imaginatively into the feelings and actions of fictitious characters in books, movies, and plays.”

The Findings

Not surprisingly, among the group of participants as a whole, there was a larger response in the ventral medial prefrontal cortex for the self as compared to either friends or fictional others. Among the participants who scored higher on trait identification in the personality inventory, however, the researchers observed a greater neural overlap in this brain region between self and fictional characters, concluding that “the neural responses for Self and Fictional Characters are more similar among individuals who regularly mentally simulate narrative experiences from the first-person psychological perspective of characters within the story.” In other words, people who habitually immerse themselves in a fictional work and strongly identify with one of its characters appear to access knowledge about that character’s identity “using the same neural machinery as they do to access knowledge about themselves.”

It seems, then, that pulling up Nick Carraway’s observation about “curious natures” and “veteran bores” while in line at Walmart likely employed some of the same “neural machinery” as I would have used to access information about myself. And while not everyone is equally capable of mind-melding with their favorite fictional characters, those of us with sufficient trait identification to fully immerse ourselves in the point of view of a protagonist may be rewarded for it by the privilege of becoming that character, in a sense, for the duration of the book or movie and even afterward, whenever we call them to our minds. It is this pleasure to which George R. R. Martin, author of the novel series that inspired Game of Thrones, was referring when he observed, “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies… The man who never reads lives only one.”

References

Timothy W Broom, Robert S Chavez, Dylan D Wagner, Becoming the King in the North: identification with fictional characters is associated with greater self–other neural overlap, Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2021;, nsab021.