Meditation

How Is Consciousness Related to the Brain?

Near-death experiences, psychedelics, and meditation provide intriguing clues.

Posted August 8, 2019 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

When I studied cognitive neuroscience as a doctoral student, I attended a discussion group that focused on the “hard problem of consciousness.” I had never thought of consciousness as a problem, but as we read classic papers on the topic, I realized just how difficult it was to explain how—and why—matter gives rise to subjective experience.

There were vigorous debates on the topic, with some members of the group arguing that consciousness eventually could be accounted for by particular patterns of activity in the brain: Once we understood exactly how the brain works, we would see how consciousness arises from it.

Others, however, argued that the awareness of our experience—the feeling of what it’s like to see the color green or to fall in love—could never be reduced to on-or-off patterns of neurons, no matter how complex the patterning. I wasn’t sure where I stood in this debate, but I agreed that consciousness was a truly difficult phenomenon to account for.

I encountered the topic of consciousness again in my research as I reviewed the brain correlates of self-related processing (e.g., recalling an autobiographical memory). Some researchers argued that their findings provided clues about the brain areas involved in consciousness itself, given the overlap between consciousness and self-awareness. However, my co-author and I found no reliable brain areas that were specifically involved in self-related processes, which would seem to bring us no closer to understanding how the brain might give rise to consciousness.

More recently, I’ve heard some truly mind-blowing hypotheses about the nature of consciousness. I recently encountered the ideas of Eben Alexander, a neurosurgeon who had a near-death experience (NDE) in 2008 which was the subject of his New York Times number-one bestselling book, Proof of Heaven. He described familiar NDE elements from his days in a meningitis-related coma—traveling through a tunnel, encountering a being of light, connecting with profound, all-embracing love.

I recently spoke with Alexander on the Think Act Be podcast, and he described a relationship between consciousness and the brain that turns conventional scientific thinking on its head. Alexander suggests that rather than creating consciousness, the brain actually limits it.

“I often say that we are conscious in spite of our brain, not because of it,” he said. “It really has to do with the fact that consciousness is fundamental.” He continued, “Consciousness is not something you can get behind. You can’t see it as a derivative from the matter of the brain.” (See "What If Consciousness Comes First?")

So if our experience of consciousness doesn’t arise from the brain, where does it come from? According to Alexander, “We truly live in a mindful universe, with top-down causal principles that are very powerful in determining the events of human lives.” He posits that these causal principles “are not the simple, predicted result of a kind of bottom-up causation looking at the subatomic particles and cells.” Instead, consciousness is the building block of the universe and gives rise to everything we experience—including ourselves.

If you find this description of reality and human experience hard to fathom, you’re in the same position that Alexander was in before his NDE. He described his current view as a “180-degree flip from what I used to believe about the primacy of the material world.” Earlier in his life, he assumed, as some in my consciousness discussion group had argued, that “consciousness was nothing more than an epiphenomenon of the chemical reactions and electron fluxes occurring in the brain.” Accordingly, he was “dismissive of any fundamental role of mind or soul, or anything like that.”

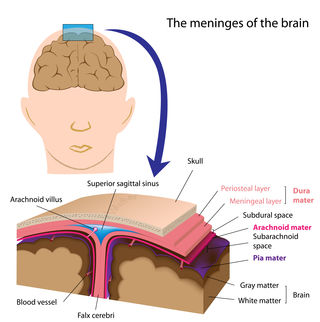

The change in Alexander’s thinking emerged after his NDE, as he struggled to understand how a brain so addled by the E. coli that caused his severe meningitis could produce such transcendent experiences as he witnessed. The damage to his brain extended throughout the cortex, and from the surface of the brain through the full thickness of his gray matter to the junction with white matter (see Figure 1).

Nevertheless, Alexander said the “spiritual aspects of that deep coma journey” were much more “rich, real, detailed, vibrant, alive, and memorable than anything I’d ever been through. I remember them as if they just happened yesterday.” In contrast, he said his memories from the first 36 hours after coming out of his coma “faded within a week or two.”

Since that time he has come to the conclusion that the brain impairment he experienced didn’t impair his consciousness, but actually allowed him to experience consciousness in a more profound way.

Psychedelic Experiences

As others have pointed out, NDEs share some features with the effects of psychedelic substances like LSD and psilocybin. Alexander notes that people who take these powerful serotonin 2A drugs have “profound, vibrant, meaningful” experiences that seem “shockingly real.”

According to Alexander, a similar mechanism underlies the psychedelic experiences and what he encountered through his NDE. In both cases, he suggests, a drop in brain activity reveals these altered experiences of consciousness. “It’s not increased activity in any brain region that leads to such extraordinary phenomenal experiences,” he said. “It’s actually the brain turning off.”

Alexander cites a 2012 paper that found that psilocybin-based psychedelic trips were associated with decreases in brain activation in certain regions, including the thalamus (the brain’s “relay station”) and the cingulate cortex. The greater the degree of deactivation in these regions, the more profound participants reported their experience to be.

Other studies have found that ingesting psychedelics causes specific areas of the brain to become less active. For example, a 2016 study found that LSD led to less activity in areas of the brain called the “default mode network” (which is postulated to underlie our sense of self); the degree of deactivation in these areas was significantly correlated with participants’ ratings of “ego dissolution.”

This study also found greater activity in the primary visual areas of the brain among those in the LSD condition, which is in line with the visual hallucinations they experienced. Researchers have found that LSD leads to a higher degree of communication among some brain areas as well, including between “normally distinct brain networks.”

Can You Get There Through Meditation?

Is it possible to have the kinds of transcendent experiences described by those who have survived an NDE or taken psychedelics, without almost dying or taking drugs? Alexander says it is. “I often get right back into that world in meditation,” he said—especially while listening to audio featuring binaural beats, like those available from Sacred Acoustics (which he co-developed). “You don’t have to have an NDE to come to a much richer understanding of your consciousness and its relationship to the universe. You can cultivate that through meditation.”

Neuroscientist and author Sam Harris agrees. He describes having had similar experiences during his meditation practice, as well as in lucid dreams and “through the use of various psychedelics (in times gone by).” Interestingly, Harris was one of Alexander’s most forceful critics around the time Proof of Heaven was released, as is evident in the article from which that last quote is taken.

A number of months ago I happened to be following a guided meditation from Harris’s popular meditation app (Waking Up) in which he suggested that our experience of consciousness as being located in the head (somewhere behind the eyeballs) was an illusion. Rather, I should consider that my head is actually located in consciousness. I was having a “medi-date” with my wife at the time, and afterward, we both expressed the mind-blowing quality of that suggestion. My head is in consciousness?

As Harris states in this video, “If you lose your sense of a unitary self—that there’s a permanent, unchanging center to consciousness—your experience of the world actually becomes more faithful to the facts. It’s not a distortion of the way we think things are at the level of the brain. It actually brings your experience into closer register with how we think things are.” And in a recent podcast episode with his wife, the author Annaka Harris, he entertains the possibility of “panpsychism,” which holds that consciousness is an inherent property of all matter.

So Harris and Alexander have intriguing areas of overlap in challenging our conventional ways of thinking about the brain and consciousness. However, noting this overlap doesn’t discount the considerable daylight between Harris’s and Alexander’s views of consciousness and its relation to the brain. For example, Alexander believes that long-term memories are not actually stored in the brain, after the initial period of encoding and consolidation that requires an intact hippocampus—an idea that Harris dismisses.

There is a meta-level to these debates about consciousness and experiences like NDEs. Prior to having his own NDE, Alexander dismissed interpretations of NDEs as supporting the reality of an afterlife and a divine being of love, as he described in Proof of Heaven and in his most recent book, Living in a Mindful Universe (co-written with Karen Newell). Most likely he would have argued against his own interpretation, before his coma experience.

In a similar way, Harris's experiences with meditation and psychedelics seem to have informed his understanding of what consciousness is, in a way that's hard to grasp for others who haven't had those experiences—speaking for myself, and others I've talked to.

Consciousness is, by definition, an inherently subjective phenomenon. Nobody else has had exactly the experience that Alexander had during his coma. Only Sam Harris knows what his meditative and psychedelic states have been. I’m the only person who had my specific death dream.

While we can study the physical effects of drugs and their phenomenological correlates and debate the facts of medical cases, perhaps ultimately their interpretation is a matter of subjectivity, based on minds unknowable by everyone but their owners. Consciousness is, indeed, a hard problem.

The full conversation with Dr. Eben Alexander is available here.

LinkedIn Image Credit: simona pilolla 2/Shutterstock

References

Alexander, A. (2012). Proof of heaven: A neurosurgeon's journey into the afterlife. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Alexander, A., & Newell, K. (2017). Living in a mindful universe: A neurosurgeon's journey into the heart of consciousness. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Books.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Erritzoe, D., Williams, T., Stone, J. M., Reed, L. J., Colasanti, A., ... & Hobden, P. (2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 2138-2143.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Muthukumaraswamy, S., Roseman, L., Kaelen, M., Droog, W., Murphy, K., ... & Leech, R. (2016). Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 4853-4858.

Tagliazucchi, E., Roseman, L., Kaelen, M., Orban, C., Muthukumaraswamy, S. D., Murphy, K., ... & Bullmore, E. (2016). Increased global functional connectivity correlates with LSD-induced ego dissolution. Current Biology, 26, 1043-1050.