Chronic Pain

Why Chronic Pain Isn't in Your Head

How a 17th-century theory still limits our understanding of pain.

Posted July 3, 2019 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

The theory that mental processes exist separately from the physical body is referred to as mind-body dualism. Dating back to the works of philosopher-scientists such as Rene Descartes in the 17th century, mind-body dualism has long since been discredited by research demonstrating the biological basis of formerly invisible mental activities such as emotions, thinking, and memory. Yet there remains one area where the belief that mental experiences exist without a physical basis stubbornly persists: chronic pain.

Although common, chronic pain is never a welcome diagnosis. When first-line treatments for pain fail, particularly in the absence of clear medical test abnormalities, patients may experience the implication that their pain symptoms are “psychological.” For a patient with chronic pain, probably already impacted in multiple areas of their life by their condition, the inference that their pain symptoms are simply "in their head" demeans their daily struggles and demoralizes their hopes for effective treatment.

We now know that there is no such thing as “psychological pain.” Studies show, for example, that “psychological pain” such as social rejection is reduced by medicines such as acetaminophen that act on areas of the brain that process pain and emotions. Nor is this a new idea: The prevailing scientific theory of pain since the mid-20th century – referred to as the Gate Control Theory – shows that pain perception is influenced by a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors. Rather than a dualistic model of mental versus physical pain, gate control theory describes mental and physical pain as indivisible, like two sides of the same coin.

To illustrate the physical basis of chronic pain symptoms, consider the following sets of analogies. Each analogy represents an example of a biologically-based sensation or condition that we experience consciously. Unlike chronic pain symptoms, however, despite the fact that we experience these analogous sensations and conditions on a psychological level, and that their treatment may even benefit from psychological interventions, no reasonable person considers them psychological conditions. The hope is that these analogies can help dispel the mind-body dualism that remains about chronic pain.

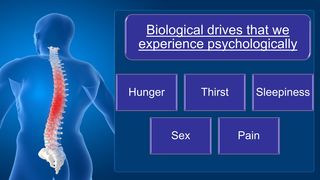

The first set of analogies refer to biological drives that we experience as feelings and urges. Pain is just one of these many biological drives. The feeling of pain acts as a kind of alarm signal that compels our attention and motivates us to remedy the symptoms. Hunger and thirst symptoms are two other common biological drives that help us maintain our health. Underlying hormones and other chemical mechanisms help our bodies monitor our need for food and drink, and trigger feelings when deficits in energy and fluid levels arise that we consciously experience as hunger and thirst. Hunger and thirst symptoms are no more “in our head” than is pain, although psychological factors affect how we experience and manage them.

Sleepiness and sexual arousal are two other primary biological drives that we experience psychologically. Although psychological factors are clearly important contributors to when and how we experience sleepiness and sexual arousal, and psychological treatments can even be effective for treating sleep and sexual problems, they are feelings caused by underlying biological activity. Chronic pain symptoms are similar: They may in some cases benefit from psychological treatments, but this does not imply that the symptoms are nonphysical in nature.

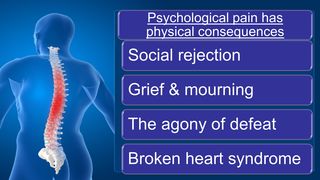

The second set of analogies represent examples of so-called “psychological pain.” Although many people consider painful psychosocial experiences as fundamentally different from physical injuries, each is regulated by the same brain regions and neurotransmitter systems. And even though we experience painful psychological events as negative emotions, they have profound physical effects. In the same way that the pain of social rejection is detectable on certain brain scans, for example, research suggests that testosterone levels decline, and heart attack rates increase, among fans of losing teams of major sports contests. Possibly the most dramatic example of the physical consequences of “psychological pain” is the condition called broken heart syndrome. This is a potentially fatal cardiovascular reaction among people suffering from grief or an acute interpersonal loss (Debbie Reynolds, the actress of mother of actress Carrie Fisher, may be one recently notable example of broken heart syndrome). Just as physical pain invariably affects the mind so too does mental pain affect the body.

Finally, consider this final set of analogies referring to common medical conditions that may sometimes benefit from psychological treatments.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S., with well-understood pathophysiology. Perhaps surprisingly, however, clinical trials show that patients with heart disease benefit from psychological treatments even beyond standard medical interventions. But these benefits from psychological therapies do not imply that heart disease is a psychological condition. No one who has experienced a migraine headache would dismiss them as “psychological.” Migraines are a miserable experience the causes of which remain poorly understood. Yet in addition to certain medicines, psychological treatments such as biofeedback and stress management are helpful for many. Similarly, insomnia affects millions of Americans, yet can often be improved by a psychological treatment called cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Lastly, research also indicates that emotional stress increases blood pressure, such as cases of white-coat hypertension, and impairs blood sugar regulation among diabetics. However, even though behavioral treatments may assist insomnia, hypertension, and diabetes, no one doubts the medical origins of these conditions.

As we are now well into the 21st century, perhaps it is finally time to modernize our view of chronic pain. Like many of our other physical and health processes, pain is a biologically-based process that is often experienced psychologically and that may in some cases benefit from psychological treatments. Eliminating mind-body dualism toward chronic pain can free patients from harmful stereotypes and maximize their options for improving their symptoms, functioning, and quality of life.