Environment

Conspiracy: Doubt Mongering

When doubt evolves into conviction.

Posted March 17, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

“To doubt everything or to believe everything are equally convenient solutions; both dispense with the necessity of reflection,” wrote the late-19th-century mathematician and philosopher Henri Poincaré (Science and Hypothesis, 1905). For the scientist, there is "virtue in doubt," as doubt, uncertainty, and healthy skepticism are essential to the scientific method (Allison et al., American Scientist, 2018). Science, after all, is driven by “hunches and vague impressions” (Rozenblit and Keil, Cognitive Science, 2002).

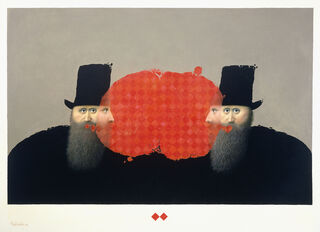

Sometimes though, there are those who exploit and co-opt doubt inappropriately (Allison et al., 2018; Lewandowsky et al., Psychological Science, 2013). These are the doubt mongers who use “science against science” to manufacture controversy. They undermine the scientific importance of uncertainty by deliberately challenging it, as, for example, with those who deny climate change (Goldberg and Vandenberg, Reviews on Environmental Health, 2019).

"Doubt is our product" became the mantra of tobacco companies (Goldberg and Vandenberg, 2019). Other industries have attempted to manipulate the legal system by the use of misleading diagnoses (e.g., referring to "miner's asthma" rather than the more deadly "black lung" disease); conflating good studies with weak studies; hiring "experts" with clear-cut conflicts of interest or their own agendas; casting doubt elsewhere (e.g., shifting blame from sugar to fat when both in excess are potentially harmful); cherry-picking data or withholding damaging findings; and waging ad hominem attacks against scientists who dare speak truth to power (Goldberg and Vandenberg, 2019).

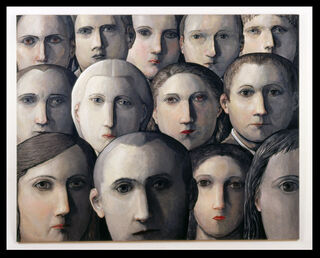

An environment rife with doubt is an environment ripe for the development of conspiracy theories, particularly in the context of the internet. We are now inundated with "informational cascades" (Sunstein and Vermeule, The Journal of Political Philosophy, 2009), an "infodemic," as it were (Teovanovic et al., Applied Cognitive Psychology, 2020), in which the "traditional watchdog role" of the media no longer exists (Butter, The Nature of Conspiracy Theories, S. Howe, translator, 2020). Further, the internet acts as a kind of online echo chamber (Butter, 2020; Wang et al., Social Science & Medicine, 2019) such that the more a claim is repeated, the more it seems credible, a phenomenon called illusory truth (Brashier and March, Annual Review of Psychology, 2020), and the more it confirms what we have come to believe (i.e., confirmation bias). Doubt evolves into conviction.

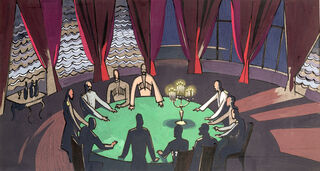

What is a conspiracy theory? It is a conviction that a group has some nefarious goal. Conspiracy theories are considered culturally universal, widespread, and not necessarily pathological (van Prooijen and van Vugt, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2018). Rather than the result of psychiatric illness or "simple irrationality," they may reflect so-called crippled epistemology, i.e., limited corrective information (Sunstein and Vermeule, 2009).

Conspiracy theories have been prevalent throughout history, though they typically come in "successive waves," often mobilized by periods of social unrest (Hofstadter, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, 1965 edition). Conspiracies, of course, do occur (e.g., plot to murder Julius Caesar), but more recently, labeling something a conspiracy theory carries a pejorative connotation, stigmatizing and de-legitimizing it (Butter, 2020).

Conspiracies have certain ingredients: Everything is connected, and nothing happens by chance; plans are deliberate and secret; a group of people is involved; and the alleged goals of this group are harmful, threatening, or deceptive (van Prooijen and van Vugt, 2018). There is a tendency to scapegoat and create an "us-versus-them" mentality that can lead to violence (Douglas, Spanish Journal of Psychology, 2021; Andrade, Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 2020). Conspiracies create meaning, reduce uncertainty, and emphasize human agency (Butter, 2020).

Philosopher Karl Popper was one of the first to use the term in a modern sense when he wrote about the "mistaken" conspiracy theory of society, namely that whatever evils occur (e.g., war, poverty, unemployment) are the direct result of the plans of sinister people (Popper, The Open Society and its Enemies, 1945). In fact, says Popper, there are inevitable "unintended social repercussions" from the intentional actions of humans.

In his now-classic essay, Hofstadter wrote that some people have a paranoid style in the way they see the world. He differentiated this style, seen in normal people, from those given a psychiatric diagnosis of paranoia, even though they both tend to be "overheated, suspicious, overaggressive, grandiose, and apocalyptic."

The clinically paranoid person, though, sees the "hostile and conspiratorial" world against him or her specifically, whereas those with a paranoid style see it directed against a way of life or a whole nation. Those with a paranoid style may accumulate evidence, but at some "critical" point, they make a "curious leap of imagination," i.e., "...from the undeniable to the unbelievable" (Hofstadter, 1965). Further, those who believe in one conspiracy theory are more apt to believe in other, even unrelated ones (van Prooijen and van Vugt, 2018).

Once conspiracy theories take hold, they are "unusually hard to undermine" and have a "self-sealing" quality: Their central feature is that they are "extremely resistant to correction" (Sunstein and Vermeule, 2009). "A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away... Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point," wrote social psychologists Stanley Schachter and Leon Festinger in their fascinating study that involved infiltrating a group whose leaders, warned by messages sent by "superior beings" from another planet, prophesied an end-of-the-world scenario. When confronted with "undeniable dis-confirmatory evidence," those in the group who had the social support of others reduced their dissonance and discomfort by rationalizing why their prediction had not happened and actually "deepened their conviction," including even zealously seeking new converts (Festinger et al., When Prophesy Fails, 1956).

Why are conspiracy theories so resistant to falsification? We are cognitive misers: Many of us tend to respond reflexively rather than reflectively and avoid thinking analytically since it is more challenging to do so (Pennycook and Rand, Journal of Personality, 2020). We tend to look for causal explanations and find meaning and patterns in random events as a means of feeling safe within our environment (Douglas et al., Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2017). Further, we tend to think we understand the world with "far greater detail, coherence, and depth"—called the illusion of explanatory depth—than we actually do (Rozenblit and Keil, 2002).

Bottom line: Conspiracy theories have existed throughout history and are ubiquitous. Those who believe are not necessarily irrational or psychologically disturbed, but believing in them can lead to violence, radicalization, and an "us-versus-them" mentality. Recently, they have taken on a pejorative connotation. Our human need to see patterns in random events and causality where none exist makes us more susceptible to their influence.

Belief in conspiracy theories is tenacious and particularly immune to correction. The internet generates an echo chamber whereby repetition creates an illusion of truth. In this environment, any doubt is more likely to evolve into a conviction.

Special thanks to Dr. David B. Allison, Dean of the School of Public Health, Indiana University, Bloomington, for calling attention to Poincaré's quotation.