Stress

Frayed, Frazzled, at the End of Your Rope: Stress & Weight?

Trying to cut one Gordian Knot of weight control

Posted April 23, 2011

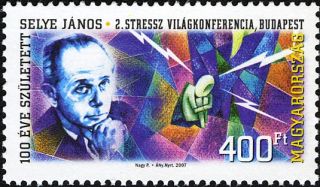

Back in the 1930s, Hans Selye, an Austrian born physician, described a characteristic adaptation syndrome that occurred when an organism was exposed to "diverse noxious agents," or "stressors." These stressors could be excessive exercise, surgical injury, drugs, or even temperature changes like exposure to cold. Selye emphasized that the body produced a classic, patterned response that was actually independent of the actual stressor. For Selye, there were three stages to this stress response: general alarm, a stage of resistance, and a stage of exhaustion or even death, if the stress is severe enough. And though the responses were highly specific, the actual stressors could be non-specific. Selye also made the point that stress did not have to be negative: it could, in fact, be positive or even healthy, such as when someone feels good when working on challenging or creative work. Selye considered stress the "salt of life." As such, he felt it was neither advantageous nor even possible to eliminate it from life. Instead, the challenge is to contain any stress and channel it into feelings of mastery.

Stress, incidentally can be either chronic or acute. When chronic, the body can develop two forms of adaptation: habituation, in which repeated exposure diminishes the effect of the stressor or facilitation (also referred to as sensitization) in which repeated exposure intensifies the effect of the stressor.

Over the years, as the word "stress" has entered common parlance, we now know so much more about the many complex physiological and behavioral responses that occur when an organism undergoes stress, whether acute or chronic. For Rockefeller University researcher Bruce McEwen, stress occurs when an individual's homeostasis or internal equilibrium is either actually threatened or perceived as threatened. McEwen emphasized that some of the most powerful perceived stresses for humans are psychological and experiential, such as those involving novelty, withholding of a reward, or anticipation of punishment, sometimes even more than experiencing the punishment itself.

Among the many reactions that occur, the body reacts to stress with a specific feedback system involving the brain's hypothalamus and pituitary gland, as well as the body's adrenal glands, called the HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis that leads to a release of a "cascade" of hormones, including cortisol. But neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, epinephrine, norepineprine, serotonin, and acetylcholine, among others, are also released. And our brain's mesocorticolimbic system, involved in anticipating, recognizing, and even remembering danger, as well as those systems involved in motivation and reward, also participate in the stress reaction.

Ironically, the process of eating, itself, can be a stress on our bodies for it is simultaneously both necessary for maintaining the body's homeostasis and a threat to its homeostasis. Researchers Power and Schulkin, in their book, The Evolution of Obesity, speak of this as the "paradox of eating." And conversely, when stressed, some people find themselves eating more, particularly the so-called "comfort foods" often high in fat, sugar, and salt, whereas others find themselves unable to eat at all.

wiIn recent years, results from animal studies have appeared that have suggested that stress itself can lead to obesity. One mechanism described is that insulin, in the presence of increased secretion of corticosterone (analogous to our human cortisol) leads to an accumulation of increased visceral ( i.e., the particularly dangerous) fat.

A very recent study in the journal Obesity by Wardle and her colleagues reports on a systematic literature review conducted to determine whether psychosocial stress actually does lead to weight gain in humans. From over 600 "potentially relevant" studies, these authors were able to include results in their final meta-analysis from only 14 research papers that met their stringent criteria of longitudinal (from one year to 38 years of follow-up), well-controlled studies from Europe and the U.S. published in peer-reviewed journals. Furthermore, the authors restricted their sample to studies that relied on actual physical measurements rather than self-reports of weight. Acknowledging that there are many types of stressors, as for example, physical, physiological, and emotional, these authors focused on "external stressors" such as "life events, caregiver stress, or work stress." They also noted that previous epidemiological research on the connection of stress to weight gain had led to "inconsistent results."

What Wardle and her colleagues found is that psychosocial stress can lead to weight gain, particularly demonstrated in those more methodologically sound studies and those with longer follow-up, though the effects were "modest and smaller than assumed in the lay literature." In fact, 69% of the studies included found "no significant relationship between stress and adiposity." The authors did find, however, that men seem to have "stronger physiological responses" (e.g. increased cortisol levels, etc.) to stress than women. Interestingly, the authors did not find that visceral fat accumulation was more "sensitive" to stress than general fat accumulation, though they acknowledge that more studies might be warranted.

The connection between stress and weight accumulation is obviously a complex one and there are many other variables, including age, genetics, other psychological states (e.g. anxiety or depression), and even eating behavior, involved. In fact, the connection may lie somewhere between being at the end of one's rope and trying to cut a Gordian Knot!