Happiness

What Will World Happiness Look Like in 2050?

The world could be much happier or much less happy in three decades.

Posted June 17, 2019 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

It seems as though people these days are increasingly ashamed about the legacy that current generations are leaving for the future. In the face of climate change and other challenges, parents seem to question whether life will be any good for their children and grandchildren.

Some say this will be a century of conflict, of desperate migration, and of increasing scarcity.

As we devote more attention to all of these concerns, and work to ensure that other species and natural systems can flourish (or just survive), I also think that it's of utmost importance to think about how life will be for humans.

So, how good will life be in 2050? Even without the huge uncertainties in environmental changes that will beset us, the scope of possible changes in biotechnology, artificial intelligence, and politics makes for an impossibly complex prediction task. It is not possible to predict the details of how life will have changed, or how happy we will be, that far in the future.

Instead, this past year, Eric Galbraith and I set out to do the next best thing.

Rather than provide country-by-country predictions of whether well-being will increase or decrease over three decades, and by how much, we asked, “What is the feasible range of changes in life satisfaction by 2050?” and “What kind of policies might be responsible for those changes?” Using data on happiness from around the world over the last 13 years, we found some remarkable patterns.

You might have noticed that in recent years, the World Happiness Reports have gained plenty of attention. The reports track changes in average life satisfaction (i.e. happiness) collected in the Gallup World Poll. Life satisfaction is a simple measure based on a single survey question, such as “Taking all things into account, how satisfied are you with your life these days on a scale of 0 to 10? Zero means completely unsatisfied, and 10 means completely satisfied.” (see my post "How Do We Measure Happiness?" for details). By now, we have a good understanding of how this life satisfaction measure captures overall well-being and we can explain a good fraction of the variation in responses among individuals, communities, cities, and countries.

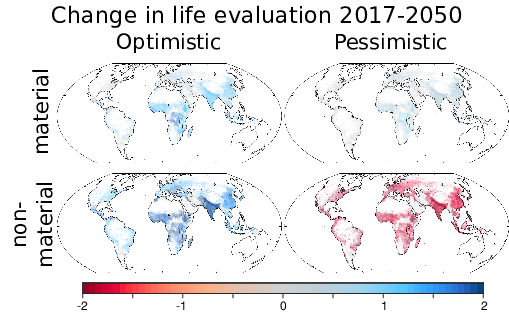

Using those data, we considered two kinds of policy objectives: (1) improving only material outcomes, represented by income and life expectancy, and (2) improving only the quality of social interactions, as represented by whether people have friends and family to count on, whether they trust their government, whether they feel a sense of freedom, and whether they help others.

It turns out that policies in the future can only make a modest difference in our happiness if they are focused on increasing material outcomes.

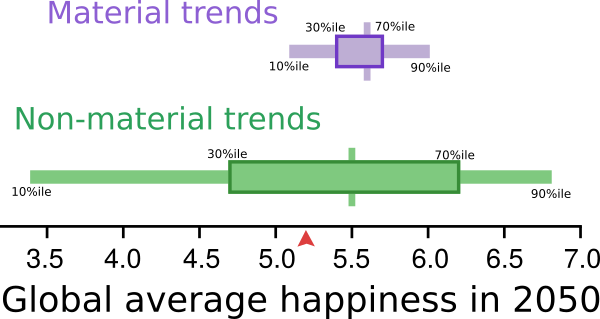

By contrast, policies that affect our social engagement, belonging, and community have the potential to radically determine our future quality of life. If we do well at these domains, life could be as good (on average) around the world as it is now in the happiest 20 countries. On the other hand, if we let these domains erode, average life satisfaction could end up as low as it is now in countries facing severe challenges.

One way to let these supports to a good life erode is to keep talking about progress and development in terms of economic growth, rather than human experience. Economists and policymakers commonly assume that boosting economic productivity is the most effective way to make societies happier. But our analysis is able to separate the material supports for happy lives from the non-material ones, using all the changes observed in 150 countries over the last decade.

What we find is that the non-material parts are where the real action is likely to be between now and 2050. The two figures above and below, and a video, each show a summary of our findings.

Technical details aside, it means that if we want life for the ten billion humans living in 2050 to be as fulfilling on average as currently in the happiest 15% of countries, rather than those currently in least happy 25%, policies must focus on how we treat each other rather than how much we consume.

Our children and future generations deserve a world in which outcomes centered around humans’ own experience of their lives are taken seriously, with income growth being only one useful tool to achieve them. This is attainable.

If we put dignity, self-efficacy, and community first, we'll also have a much easier time leaving behind a less battered, or even restored, natural world.

References

Barrington-Leigh, C. P. & Galbraith, E. (2019). ``Feasible future global scenarios for human life evaluations'', Nature Communications, Volume 10, Number: 161, doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08002-2.