Media

Addicted to Twitter? Here's Why

Why we get hooked and what we can do to break the habit.

Posted February 6, 2019 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Twitter can feel like a constant upstream struggle. Swimming against a current of non-stop tweets, catching our breath as we get to the top of the scroll, only to be clobbered by another wave of content that sends us swirling back downstream. To stay afloat, we refresh, swipe, click, post, retweet, refresh...

What’s going on here?

Twitter’s mission statement is "to give everyone the power to create and share ideas and information instantly, without barriers."

If we have a great idea, we can share it—nothing gets in the way. If we see something newsworthy, with the simple click of a button, we can spread the word to millions. And occasionally, we win the lottery when our post goes viral, or we tweet to a celebrity and they tweet back. So why do we get obsessed with constantly checking our twitter feeds and posting, even while lying awake at 3 a.m.?

How Twitter Hacks the Brain

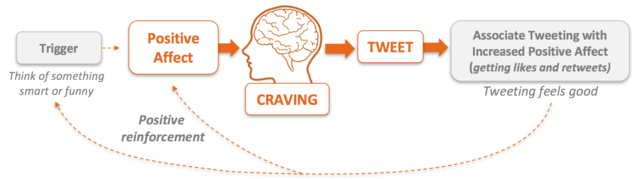

From a psychological standpoint, Twitter taps into our natural reward-based learning processes: trigger, behavior, reward. (For more information about this, see my TED talk.) We have an idea or think of something funny (trigger), tweet it out (behavior), and receive likes and retweets (reward). This learning process causes a dopamine rush in reward centers of the brain, the Nucleus Accumbens.

The more we do this, the more this behavior gets reinforced. Based on the evolutionary adaptive survival process that helps us remember where food is, our brains are now learning a new habit loop of survival: we can even track our own “relevance” by the number of impressions, tweets, and followers we have.

The Dark Side of Twitter

The harmful side of Twitter comes in the same form. We feel angry at someone’s tweet, our brain screams "do something!" and we instantly send a rage-filled tweet @ that person. Same basic learning process, yet the reward comes in two forms: (1) Self-righteous vindication. “Yeah, I got that guy!”); and (2) Approval. “Yeah, you got that guy!” someone tells us through a like or retweet. Another dopamine rush for your brain’s reward center.

But wait, there’s more: If we have a bunch of followers (who often share our particular view of the world), and we want to target a particular person, we can send out a nasty tweet and gleefully watch as trolls descend, feeding off each other in a frenzy to wipe our intended victim into oblivion. Countless people have been bullied off of social media (not just Twitter!) in this way.

We should ask sobering questions about the dark side of Twitter: As humans, why can it be so “rewarding” to be so hateful? And deep down, are we all like this?

The Science Behind Social

Looking at these questions from a scientific standpoint, we know that reward-based learning is one of the oldest learning processes among living things. With only 20,000 neurons (we humans have approximately 86,000,000,000), sea slugs learn the same way as we do: The same positive and negative reinforcement loops are at play. Yet, with social media, there’s a critical part of this feedback loop that goes missing (or is easy to ignore): negative feedback.

We learn best through positive and negative feedback. Feedback keeps us on course. Importantly, most of this comes non-verbally. It’s debatable just how much learning is non-verbal (the most influential research is pretty old, but pegs words at only 7%. (See this Psychology Today article for more.)

When we’re face to face with someone, we see the results of our actions both in body language and tone of voice. And with all of this feedback, it becomes pretty clear if we’ve hurt someone or not. We are in the moment seeing what we’ve done. This is critical, as ethics experiments have repeatedly shown that we act differently if we feel personally involved vs. doing something “out there” to someone we don’t know or if we can’t see how our actions have affected someone.

Put simply, if what we did feels bad, we stop doing it. Abraham Lincoln summed it up: “When I do good, I feel good. When I do bad, I feel bad. And that’s my religion.”

Have we lost our religion, or does social media warp our feedback loops?

With social media, we can’t see the immediate results of our actions, so the feedback we get is only from ourselves (and perhaps from others who may be egging us on). We replay the tweet in our head, justifying or rationalizing our action through an additional, self-reinforcing feel-good hit of dopamine. And through these skewed feedback loops, some of us have even learned to associate hurting others with pleasure. Yikes.

Breaking the Cycle

So what can we do if we find ourselves firing off angry tweets or ruminating over something someone tweeted at us? Understanding the process is half the battle. Knowing how our brains work can help us identify the habit loops we’ve fostered so that we can break out of them.

Developing awareness practices, like mindfulness, can be also instrumental in paying attention to the results of our actions. We put ourselves in the shoes of the person on the other end of our tweet. How would I receive this tweet? What would this feel like to me?

This helps with the lack of feedback inherent in Twitter. This opens the space not to feed those moments when we have a seemingly uncontrollable urge to unleash our “beautiful Twitter account” on someone. It might even change the reward dynamics. Instead of feeling that excited, self-righteous “I-showed-him” reward, we might even be able to notice what it feels like to hold back. And being nice is not overrated—it actually feels pretty good, or better.

References

The Craving Mind: From Cigarettes to Smartphones to Love – Why We Get Hooked and How We Can Break Bad Habits. By Judson Brewer. Foreword by Jon Kabat‑Zinn (Yale University Press, 2017).