Scent

How Do Nostalgic Scents Get Woven Into Long-Term Memories?

The "smell brain" uses top-down functions to encode long-term memories of scent.

Posted December 25, 2017 Reviewed by Davia Sills

What specific smells remind you of the holiday season? For me, one of the most poignant Christmastime scents is the blend of citrus and clove.

In elementary school, I made orange pomanders a few times. Having the oils from the orange peel spritz onto my fingertips and mix with the clove oils permanently etched this fragrance into my mind as being synonymous with Christmas. Anytime I get an aromatic whiff of an orange spiked with cloves, it instantly triggers Proustian flashbacks to my youth and "remembrance of things past" stored in my long-term memory banks.

Our nostalgic memories of the holidays are almost always interwoven with specific scents. For example, an interesting bit of consumer trivia this holiday season is that the uptick in artificial Christmas tree use caught the makers of Balsam Fir home fragrance diffusers off guard. Apparently, scent manufacturers underestimated how important it is for people with a synthetic tree to actually have their house smell like a real Christmas tree this time of year. Notably, the makers of the hugely popular "Frasier Fir" line of products (which flawlessly captures the "smell of Christmas" in a bottle) can't keep their diffusers in stock this season.

Even though we all know from life experience that scent is directly tied to many of our long-term memories, the complex neural mechanisms behind this process have remained a mystery. Therefore, two German neuroscientists, Christina Strauch and Denise Manahan-Vaughan from the Ruhr-Universität Bochum department of neurophysiology, set out to investigate the exact synaptic plasticity mechanisms responsible for storing odors as long-term memories using state-of-the-art technology. Their findings were recently published in the journal Cerebral Cortex.

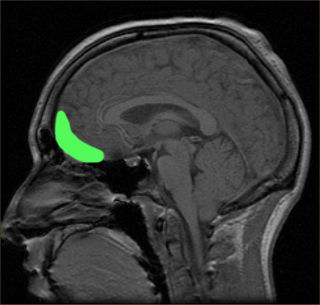

In their study on Wistar rats, the German researchers identified that the piriform cortex, which is a central part of the primitive olfactory "smell" brain located down near the brainstem at the base of the skull, relies on higher functions of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) to encode long-term memories associated with a scent.

Neuroscientists have known for some time that the piriform cortex is capable of storing temporary olfactory memories. However, this is the first time researchers have pinpointed the pivotal role that brain regions seated in the frontal lobes play in the encoding of long-term olfactory memories.

In a statement, Christina Strauch said, "Our study shows that the piriform cortex is indeed able to serve as an archive for long-term memories. But it needs instruction from the orbitofrontal cortex—a higher brain area—indicating that an event is to be stored as a long-term memory." Interestingly, the descending olfactory inputs rather than ascending olfactory inputs appear to be the key to weaving nostalgic scents into long-term memories.

As the authors state in their conclusion: "This top-down instruction of the piriform cortex by the OFC seems quite intuitive given the known involvement of the piriform cortex in odor discrimination and odor rule learning (Roman et al. 1987; Chaillan et al. 1996; Saar et al. 1998; Cohen et al. 2008, 2015), along with the role of the OFC in supporting odor discrimination and categorization. This finding also suggests that top-down control of olfactory information processing is a major determinant of long-term information storage in the piriform cortex and that the piriform cortex may serve as a repository of memories with regard to odor discrimination and categorization."

References

Christina Strauch and Denise Manahan-Vaughan. "In the Piriform Cortex, the Primary Impetus for Information Encoding through Synaptic Plasticity Is Provided by Descending Rather than Ascending Olfactory Inputs." Cerebral Cortex (First published online: November 24, 2017) DOI: 10.1093/cercor/bhx315