Adolescence

10 Ways to Stay Connected with Your Adolescent

The challenge of parenting a teenager is staying connected as you grow apart.

Posted April 27, 2015 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

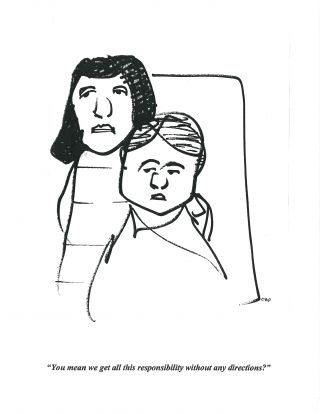

"You mean we get all this responsibility without any directions?"

This blog post comes out of a talk with parents of teenagers during which a lot of questions dealt with the difficulty of staying connected to their young person during adolescence, that age of mutual detachment when both parties struggle with the challenges of maintaining a satisfying closeness while increasingly letting each other go.

For parents, detaching and letting go of their teenager does not mean abandonment. It means allowing more freedom so the young person can learn worldly knowledge from broader experience, and more responsibility from dealing with consequences that choices bring. At the same time, parents must remain an essential player in the teenager’s life during this trial and error process of growing up.

In no particular order, what follows are 10 suggestions for staying connected with their changing teenager as adolescence grows them apart—which it is meant to do.

1. Bridge Differences with Interest. Twin goals of adolescence are developing an independence that works and an individuality that fits. A fitting individuality is only discovered from experimenting with different interests and images, usually contrasted to those of the child and to those of parents. Confronting an unfamiliar interest in their teenager (entertainment, recreational, or social, for example), and one not to their tastes, parents may choose to criticize or simply ignore it, treating it as one more difference that is setting them apart.

Instead, they could choose to bridge the difference with interest, asking if the teenager would explain or tutor them in what they have no experience understanding. “Can you help me appreciate me what you love about that music?” “Can you show me how to play that computer game?” Now, not only does the difference become a vehicle for connection, but it does so in an esteem-filling way for the adolescent. Cast in the role of expert, the teenager can act as teacher while the parent assumes the role of student wanting to learn. If you want to stay connected as your teenager differentiates, bridge emerging differences with interest.

2. Use Non-Evaluative Correction. Misunderstandings, mistakes, misdeeds are all part of the faltering path forward that young people follow through adolescence. Sometimes in frustration at a youthful misstep, parents will indulge in criticism or even condemnation: “Keep acting this way and you’ll never grow up!” Dooming the future does not encourage reform; it engenders discouragement. A negative parental judgment at the point of correction (“How could you have done such a stupid thing?”) reduces the incentive to change by increasing defensiveness against the hurtful charge.

The rule is: at correction points, do not attack character; address choices only. The mantra is: “We disagree with the choice you have made, this is why, this is what we need to have happen now, and this is what we hope you can learn.” If you want to stay connected when asserting discipline, use non-evaluative correction.

3. Stick to Specifics. There are of course times when parents need to address some point of concern with their adolescent. During these encounters, the choice of language can make a significant difference, whether the parent talks in abstract/general or specific/objective terms. For example, in frustration, telling the adolescent she is being “inconsiderate” and “irresponsible” for her recent conduct certainly communicates parental dissatisfaction. However, this use of generalities doesn’t encourage the adolescent to connect and collaborate with them on a solution to the problem.

Rather, she disconnects, feeling attacked by such abstract name-calling. She is more inclined to self-defense than open discussion. Better to stick to a specific statement using what psychologist John Narciso calls “operational” language – talking in concrete terms about the behaviors, happenings, or events that need to be addressed. Parents can state their complaints by objectively describing their cause of concern. “We need to talk about your borrowing our belongings and then returning them in a damaged state.” If you want to stay connected during normal objection points, stick to specifics.

4. Value Arguments as Communication. A form of active adolescent resistance is more arguing with the parental powers that be. Most parents don’t welcome this opposition, quickly wearying of it, often wanting to shut it down. “Stop arguing with me!” However, adolescent arguing is the young person telling a lot about themselves as they declare whatever it is they want or don’t want to have happen and why. Shut arguing down and not only do parents disconnect communication but they lose the chance to learn more about the teenager from their prime informant, the adolescent themselves.

Certainly they can address the language used so that it is respectful and safe. The question for parents to ask themselves, however, is whether they want a "speaking up" or a "shutting up" adolescent? The teenager who never argues is much harder to know and is often more evasive to deal with. What works better is parents giving the young person a full hearing, even encouraging argument out. “Can you tell me more? Can you help me better understand.” If you want to stay connected as differences between you and your adolescent naturally grow, treat arguments as valued communication.

5. Welcome Adolescent Friends. As the growing adolescent wants less time with parents and more with peers, parents can feel socially set aside, even feel threatened by this competing social attachment. However, treating the teenager’s companions as social competition or even as the enemy because they represent unfamiliar social differences can cause parents to disconnect from their teenager by refusing to accept her or his friends.

Friends are part of one’s growing social identity. By rejecting these associations, parents not only end up rejecting their adolescent, but they also allow ignorance from noncontact to amplify fears of their teenager’s new companions. A huge part of parents getting to know their adolescent is getting to know and interact with her or his friends. If you want to stay connected as your adolescent builds an independent social world, welcome adolescent friends.

6. Provide Family Structure. Although the adolescent pushes for independence from parents and is intolerant of their restraints, she still complies more than she resists. Why is that? Unlike the child who believes parents can command obedience, an adolescent now knows parents have no power to make her or stop her without her agreement and consent. “My choices are up to me!” This is a scary amount of freedom to possess. It is more than she can safely manage, and she knows it.

In consequence, she reluctantly goes along with most of the family structure that parents provide — how they make demands, establish limits, organize routines, set expectations, give and deny permissions, supervise responsibilities, prescribe rules, require information, and provide direction and support. Every time she interacts with some aspect of family structure, whether in consent or complaint or conflict, the adolescent connects herself to that primary social unit. If you want to keep your adolescent connected to family, keep that family structure firmly in place.

7. Stay Accessible for Listening. It’s a common timing problem in communication between adolescents and parents. When the parent is ready to listen, the adolescent isn’t ready to talk; and when the adolescent is ready to talk, the parent isn’t ready to listen. What typically gets in the way of the adolescent talking is not being in the right frame of mind or mood to open up. What typically gets in the way of the parent listening is being busy or tired. And what typically gets in the way of talking and listening for both is a preoccupation with higher priority electronic communication and entertainment.

Talking + listening = connecting. If parents put off listening to their teenager until a more convenient later time, when "later" comes, the openness to talking may be closed and the chance for connecting lost. If you want your adolescent to connect through communication, be accessible to listen at the time he wants to talk, and be willing to shut off or set aside other electronic diversions when you do.

8. Express Appreciation. It’s easy for parents to forget the adolescent effort it takes to do what they want and not do what they don’t want. It’s tempting to simply take these positive acts of commission and omission for granted and let them pass unnoticed. However, marking them with parental appreciation turns them into powerful connection points. “I appreciate you taking care of homework without having to be asked.” “I appreciate you not going along with what your friends decided to do.” Appreciation is an act of recognition and goes counter to the common adolescent complaint: “My parents don’t notice how much I do!”

What tends to command parental attention is what goes wrong. However, mostly paying attention to problems with teenagers risks the young person coming to believe that he is nothing but a collection of misdeeds and mistakes. Worse, sense of standing in the family can be affected by continual negative notice. The lower one’s valued standing the family, the more disconnected from family one is likely to feel. If you want your adolescent to feel connected as a valued family member, express appreciation for the good they do and the bad they don’t.

9. Support Adult Friendships. Once adolescence begins, peers are really important for the same-age understanding and companionship they provide, although the outlook and experience they offer is immature. To help the young person connect with her older self and more mature potentialities, the influence of adult friends can help. Of course parents are the most salient adults, but because of their governing authority, they can’t really be just friends. However, they can support the development of adult friendships elsewhere. Connecting with these adults, the adolescent can accept feedback, advice, and valuing which, if it came from parents, would more likely be discounted or discredited. “You’re just saying that because you’re my parent!”

These adults can come from many quarters — teachers and coaches at school, adults in the extended family, youth activity directors, adult friends of parents, parents of peers, mentors, employers, tutors, and the like. If you want your adolescent to feel connected to the older generation and not just the younger one of peers, and to older potentialities, support adult friendships.

10. Offer Positive Choice Points. The great vulnerability detachment when parenting an adolescent — who is in the process of detaching from childhood and from them — is becoming less positively responsive and more negatively disposed. There is inevitable wear and tear on parents from coping with more separation, differentiation, and opposition as the teenager grows. This change is partly why detachment parenting an adolescent is more challenging than attachment parenting a child. Finding it harder to accept and enjoy, and easier to object and correct, parents can reduce positive overtures to their adolescent, and the relationship can suffer. “You’re less fun to be with than you used to be” charges the teenager. And he isn’t lying. But what makes positive parental initiatives additionally difficult is how the adolescent often rejects their invitations. “Not right now.” “I don’t feel like it.” “I don’t want to.”

Parents must not be deterred by such rejections, because sometimes the adolescent will accept an invitation for talking together, sharing together, laughing together, vacationing together, and even working together. And when this acceptance is given, a satisfying connection is made. If you want to stay connected with your adolescent, keep offering positive choice points for engagement, even when these invitations are frequently refused.

Connected parenting an attached child comes easier than connected parenting a detached adolescent, but by hanging in there it can be done.

Next week’s entry: Adolescence and Honoring Agreements