Sleep

The Mystery of Narcolepsy

For some, dreams can come at inopportune times, sometimes with dire consequences

Posted April 3, 2013

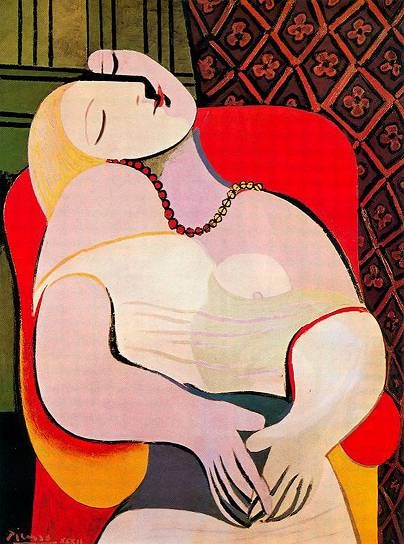

Picasso’s Le Rêve (The Dream). The loss of muscle tone in the neck suggests rapid eye movement sleep.

Most of us dream two to five times each night. Our dreams can be thrilling and beautiful, frightening, or unmemorable. For some, dreams come at inopportune times of day and may be misinterpreted as hallucinations, with dire consequences to the individual.

In my previous blog post, Collateral Damage, I described the repetitive dreams of PTSD patients whose trauma spanned the last half century — from the Holocaust survivor to the veteran returning from Afghanistan. Here, I look at the dreams and other symptoms that arise from narcolepsy — a difficult and dangerous sleep disorder that can elude diagnosis. I introduce three patients whose stories stopped me in my tracks — sometimes to intervene medically, sometimes to ponder how little we actually know about the science of sleep.

“Your patient has been admitted to a psych ward”

Several years ago, while working in my sleep clinic, I received a routine phone call from a resident physician working in a psychiatric hospital to inform me that a 12-year-old patient that I had been treating for a sleep disorder had been admitted to a psychiatric ward. He told me that the patient had been having hallucinations, and probably had schizophrenia. However, I spent the next several hours getting the young patient out of the psychiatric hospital, because he did not have schizophrenia but rather the classic symptoms of narcolepsy. The resident psychiatrist, who knew nothing about narcolepsy, had misinterpreted the patient's symptoms. One can only imagine the consequences of admitting an impressionable teenager to a psychiatric hospital having been incorrectly diagnosed.

“I knew that the children on the road were actually not there”

In a second case, my patient was a school bus driver, a woman in her mid-20s with a history of sleepiness that began in high school. She had fallen asleep driving and had been referred to our sleep disorder center. She had narcolepsy, and one of her principal symptoms, besides being very sleepy during the day, was vivid dream imagery as she was falling asleep at night. At times she could not tell whether she was awake or asleep. Often, when she drove, she would see children in the road, but she knew they were not really there, and would simply continue driving.

“I could not control my day dreams”

A third patient was referred to me by a military physician who mistakenly thought his new recruit, in her early 20s, had narcolepsy. He wanted confirmation of the diagnosis so that she could be discharged from military service. During classes she often experienced vivid daydreams, which the physician was convinced were the hallucinations of narcolepsy. Indeed, the patient did have disturbing symptoms, including severe sleepiness, and when tested, she fell asleep almost instantly during her overnight sleep test and experienced an enormous amount of deep (or slow wave sleep).

The following day, she had a test in which she was given the opportunity to nap for 20 minutes every two hours. She fell asleep in less than five minutes each time she napped, and each time she had rapid eye movement sleep. On the surface, she did exhibit the classic signs of narcolepsy, but there was the fact that these symptoms had begun at boot camp. When I reviewed her sleep/wake schedule at the military base, it turned out that she was only sleeping for about four out of every 24 hours because of the guard duty she was ordered to do. I therefore declined to confirm that she had narcolepsy, and ordered that she be given the opportunity to sleep a minimum of eight hours per night and then be retested. After two weeks on the schedule, the patient was retested, and her results were absolutely normal. She did not have narcolepsy at all.

Causes

Narcolepsy is a chronic disorder of the central nervous system which in most patients is caused by a loss of about 10,000 to 20,000 of the many billions of neurons in the brain. The neurons are located in a tiny region of the brain (the hypothalamus) and they produce a chemical called orexin (also called hypocretin) that is involved in sleep/wake regulation. It is believed that narcolepsy has both a genetic component and an autoimmune component. People are not born with narcolepsy. The symptoms usually appear out of the blue, but more rarely after a mild infection, or after traumatic brain injury or even concussion. In most cases, the symptoms of narcolepsy begin in the mid-teenage years. Specific gene variations have been reported in the past month that show a strong association with the age when some of the symptoms appear. Exactly what triggers the onset is a mystery that is being unraveled.

A chemical trigger in some children.

In the winter of 2009–2010 the world was trying to contain an epidemic of the H1N1 virus (Swine Flu). A vaccine containing an “enhancer” called ASO3 was widely used in Finland, Sweden, the U.K., and some other countries. Vaccination with this product resulted in some children and young adults with genetic susceptibility developing narcolepsy. This vaccine was never approved for use in the US.

Symptoms

Untreated, narcolepsy patients are almost always sleepy. In addition, people with narcolepsy may experience irresistible and sudden bouts of sleep which can last up to several minutes. People may fall asleep while at work or school, while eating or conversing, or while driving or operating dangerous machinery.

Patients with narcolepsy have the manifestations of REM sleep at the wrong times in the wrong places. These manifestations are sleepiness, dream imagery, and loss of muscle tone (paralysis) in various degrees. These symptoms can occur when the patient is awake. The dream imagery can occur as the patient is falling asleep (hypnagogic hallucinations) or after awakening (hypnopompic hallucinations). The patient may awaken from a dream and be paralyzed for a few seconds or minutes. Patients may also lose muscle tone in response to strong emotions (cataplexy). With such striking symptoms in many patients, it is surprising how often the diagnosis is missed.

« VIDEO: Your pet may have narcolepsy »

Narcolepsy has been described in several breeds of dog (as illustrated by this video, "Sleepy Spudgy," that I encountered on YouTube), including Doberman Pinscher, Labrador Retriever, Poodle, Dachshund, and some mixed breeds.

Treatment

We don’t know how to cure narcolepsy, but we are able to control many of the distressing symptoms. In most cases it is best that patients be diagnosed by someone very familiar with this disease — most often a board-certified sleep specialist or a neurologist. To treat the symptoms of sleepiness we use medications to increase alertness (examples include modafinil and armodafinil) or that make sleep “deeper” (example, sodium oxybate). The latter named product and some antidepressants (that reduce REM sleep) may be used to treat the other symptoms. Strategically timed naps in the afternoon may also help boost alertness during the day.

Lessons learned

The cases above suggest that many doctors do not know enough about sleep disorders in general, and narcolepsy in particular. In a study I published about 10 years ago, it was found that patients with narcolepsy were very likely to be treated for mental disorders. Even though they saw medical practitioners much more often than the general population, the correct diagnosis was rarely made, even when their symptoms were classic. As the second case showed, a diagnosis may be missed for more than a decade. This delay in diagnosis still occurs, as reported last month.

The second case also teaches us that patients with narcolepsy usually can distinguish between dreams and reality, whereas patients with schizophrenia may believe their hallucinations are real. I have had patients who have both hypnagogic hallucinations and schizophrenic hallucinations, and they were able to tell which was which.

The third case demonstrates that chronic sleep deprivation can have many manifestations, one of which may cause a person to go into REM sleep and develop symptoms that resemble narcolepsy.

The good news!

We know how to diagnose narcolepsy, and although we can’t cure it, we have good treatments for it. Unrecognized and untreated, narcolepsy can cause a child to fail or drop out of school and ruin their life. We have had patients whose lives were turned around with treatment: they excelled in school and became successful in various professions, including medicine.

Resources

Finding a sleep specialist: American Academy of Sleep Medicine Search Engine; NSF Search engine

eBook for the public. Chapter 13, The iGuide to Sleep

Up to the minute research on narcolepsy: The U.S. National Library of Medicine