Fear

Why Clowns Creep Us Out

The psychology of ambiguity explains why clowns can freeze us with uncertainty.

Posted October 14, 2016

For the past several months, "creepy clowns" have terrorized the United States, with sightings in at least 33 states. They have been reported in more than a dozen other countries as well. These fiendish clowns have reportedly tried to lure women and children into the woods, chased people with knives and machetes, and yelled at people from cars. They’ve been spotted hanging out in cemeteries and on the side of desolate country roads in the dead of night.

This isn’t the first time there has been a wave of clown sightings in the U.S. After eerily similar events occurred in the Boston area in the 1980s, Loren Coleman, a cryptozoologist who studies the folklore behind mythical beasts such as Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster, came up with “The Phantom Clown Theory,” which attributes the proliferation of clown sightings to mass hysteria (usually sparked by incidents witnessed only by children).

It’s impossible to determine which of these incidents are hoaxes and which are bona fide tales of clowning taken to the extreme. Nonetheless, the perpetrators seem to be capitalizing on our longstanding love-hate relationship with clowns, and tapping into the primal dread that so many children (and more than a few adults) experience in their presence.

In fact, a 2008 study conducted in England concluded that the common practice of decorating a hospital children’s ward with pictures of clowns may create the exact opposite of a nurturing environment - for the most part, the kids in the hospital did not like the pictures at all. (It’s no wonder so many people hate Ronald McDonald.)

But as a psychologist, I’m not just interested in pointing out that clowns give us the creeps; I’m also interested in why we find them so disturbing. Earlier this year I co-authored a study with one of my students, Sara Koehnke, “On the Nature of Creepiness,” which was published in the journal New Ideas in Psychology. While the study did not specifically look at the creepiness of clowns, much of what we discovered helps explain this phenomenon.

March of the Clowns

Clown-like characters have been around for thousands of years. Historically, jesters and clowns have been a vehicle for satire and poking fun at powerful people. They provided a safety valve for letting off steam and granted unique freedom of expression—as long as their value as entertainers outweighed the discomfort they caused higher-ups.

Jesters and others persons of ridicule date back at least as far as ancient Egypt. The English word “clown” first appeared in the 1500s, when Shakespeare used the term to describe foolish characters in several of his plays. The now familiar circus clown—with painted face, wig, and oversized clothing—arose in the 19th century and has changed little during the past 150 years.

The trope of the evil clown is nothing new, either: Earlier this year, writer Benjamin Radford published Bad Clowns, which traces the evolution of clowns into unpredictable, menacing creatures.

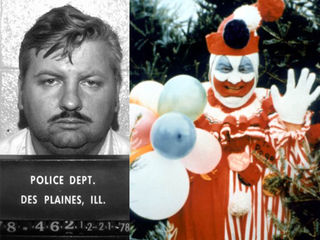

The persona of the creepy clown came into its own after serial killer John Wayne Gacy was captured. In the 1970s, Gacy appeared at children’s birthday parties as Pogo the Clown and also regularly painted pictures of clowns. When the authorities discovered that he had killed at least 33 people, burying most of them in the crawl space of his suburban Chicago home, the connection between clowns and dangerous psychopathic behavior became forever fixed in Americans' collective unconscious.

Following the notoriety of Gacy, Hollywood exploited our deep ambivalence about clowns via a terror-by-clown campaign that shows no signs of going out of fashion. Pennywise, the clown from Stephen King’s 1990 movie It, may be the scariest movie clown. But there are also the Killer Klowns from Outer Space (1988), the scary clown doll under the bed in Poltergeist (1982), the zombie clown in Zombieland (2009), and, most recently, the murderous clown in All Hallow’s Eve (2013).

The Nature of Creepiness

Psychology can help explain why clowns—the supposed purveyors of jokes and pranks—often end up sending chills down our spines. My research was the first empirical study of creepiness. I had a hunch that feeling creeped out might have something to do with ambiguity—about not really being sure how to react to a person or situation.

We recruited 1,341 volunteers, ranging in age from 18 to 77, to complete an online survey. In the first section of the survey, participants rated the likelihood that a hypothetical “creepy person” would exhibit 44 different behaviors, such as unusual patterns of eye contact or physical characteristics like visible tattoos. In the second section, participants rated the creepiness of 21 different occupations. In the third section they simply listed two hobbies that they thought were creepy. In the final section, participants noted how much they agreed with 15 statements about the nature of creepy people.

The results indicate that people we perceive as creepy are much more likely to be male than female (as are most clowns), that unpredictability is an important component of creepiness, and that unusual patterns of eye contact and other nonverbal behaviors set off our creepiness detectors.

Unusual or strange physical characteristics such as bulging eyes, a peculiar smile, or inordinately long fingers did not, in and of themselves, cause us to perceive someone as creepy. But the presence of weird physical traits can amplify other creepy tendencies that a person may exhibit, such as persistently steering conversations toward peculiar sexual topics or failing to understand a policy that does not permit people to bring reptiles into the office.

When we asked people to rate the creepiness of different occupations, the one that rose to the top of the creep list was, you guessed it: Clowns.

The results are consistent with my theory that feeling “creeped out” is a response to the ambiguity of threat, and that it is only when we are confronted with uncertainty about that threat that we get the chills.

For example, it would be considered rude and strange to run away in the middle of a conversation with someone who is sending out a creepy vibe, but who is actually harmless. At the same time, it could be perilous to ignore your intuition and engage with that individual if he is, in fact, a threat. The ambivalence leaves you frozen in place, wallowing in discomfort.

This reaction could be adaptive, something humans have evolved to feel, meaning that being creeped out is a way to maintain vigilance during a potentially dangerous situation.

Why Clowns Set Off Our Creep Alert

In light of our study’s results, it is not at all surprising that we find clowns creepy. Rami Nader, a Canadian psychologist who studies coulrophobia, or the irrational fear of clowns, believes that clown phobias are fueled by the fact that clowns wear makeup and disguises that hide their true identity and feelings. It has been estimated that approximately 2% of adults have a fear of clowns.

This is consistent with my hypothesis that the inherent ambiguity surrounding clowns makes them creepy. They seem happy, but we don't know if they really are. And they’re mischievous, which puts us constantly on guard. When we interact with a clown during one of his routines, we don't know if we're about to get a pie in the face or be the victim of another humiliating prank. The highly unusual physical characteristics of the clown (the wig, the big red nose, the makeup, the odd clothing) only magnify the uncertainty of what he might do next.

There are certainly other types of people who creep us out—taxidermists and undertakers are also high on the creepy occupation spectrum. But they have their work cut out for them if they aspire to the level of creepiness we attribute to clowns. In other words, they have big shoes to fill.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.