Ever since Sophocles banned him from the stage, Laius has remained the one we know by hearsay, the one we never see. He exerts his power through the speech of others, always evoked, never present—unlike Hamlet's father, he never stakes his claims himself. Sophoclean Laius, then, easily lends himself to Lacanian readings as the quintessential absent father, powerful not despite but because of his death, and it is no accident that Lacanian paternity can only be articulated on the basis of Oedipal filiality.

~ Weineck (2010)

Asante sana Squash banana, wewe nugu mimi hapana.

~ Rafiki, fictional baboon, on father-son relations

The key to psychoanalysis is the Oedipus complex. The little boy wants to have (sex with) his mother. He is afraid that if he succeeds, his father will castrate him. To get mother and avoid castration, he wants to kill his father. That too turns out to be unrealistic, and so he identifies with his father and his proscriptions, becomes a cultured man and develops various psychopathologies along the way. Freud says little about how the father feels about this. Indeed, he cannot because the father’s psychology lies in his own boyhood and that is long past. How much competition does the father perceive from the boy? Is it enough to motivate infanticide; is it enough to justify the boy’s fears?

The father’s psychology is one of mixed emotions. On the one hand, he has an interest in having sons who will become strong, successful men; on the other hand, he is afraid of eventually losing his position of dominance, become weak, and die. For some men, the second motive dominates until the end. Freud himself is an example. He tolerates his disciples, his intellectual sons, only to the extent that they do not threaten the core assumptions of his psychoanalysis. By holding them in positions of submission, he can only despise them or drive them away. Abraham and Jones never rebel; Jung and Adler stake their own claims; Rank and Ferenczi just slip away. None of them succeeds in killing and replacing Freud, although Jung may have thought he did. By holding on to his tyrannical supremacy until cancer finally fells him, Freud fails to reap the fruits of his maturity. His dutiful sons never surpass him intellectually; they never take psychoanalysis to greater heights (Who does Jonesian analysis these days?). The apostates set up new systems so different that they cannot be recognized as psychoanalysis. Jung becomes a new-ager and Adler a social psychologist.

What could Freud have done differently? He could have sought, however unconsciously, to become a victim of parricide. He could have, in due time, allowed the motive of having great sons to predominate. He could have stepped aside when his ablest disciples came into bloom (such as Rank). Or better yet, he could have put up some fight, knowing that it would be his last one. He could have retired into the elder-statesmanhood of the movement. He chose not to and thereby enshrined the ossification of his creation.

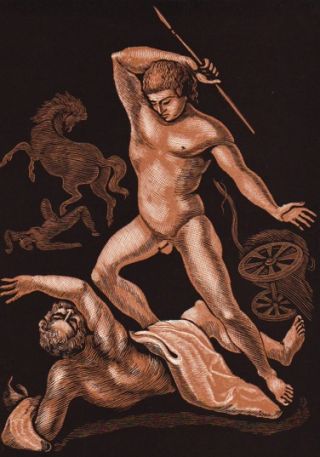

I broke with Freud (give me some license with the writing here, please) when I realized that the father’s wish to be surpassed may be a powerful (un)conscious force. My interpretation of the Oedipus-Laios story is that, coming to the bridge, King Laios knows (unconsciously) that the moment of death has come. He will be (and wants to be) killed by his son. This is a great and tragic vision. Laios departs as a warrior, knowing that he is being replaced by his own offspring, a man who has proven his worth by killing the greatest warrior, his father. If the timing is right, this is a greater death than being killed by a despised enemy, one’s wife (think Agamemnon) or by hideous disease. Indeed, Laios has a greater death than Oedipus or Freud. The secret of power is knowing when to let it go.

Carl Gustav Jung put the Laios dilemma thus: To be fruitful provokes one's downfall, at the rise of the next generation, the previous one has exceeded its peak. Our descendants become our most dangerous enemies for whom we are unprepared. They will survive and take power from our enfeebled hands.

For a personal memory, see here.

Jung, C. G. (1916). Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido. Transl. by B. M. Hinkle. New York.

Weineck, S.-M. (2010). The Laius syndrome, or the end of political fatherhood. Cultural Critique, 74, 131-146.