What can we learn about today's yoga culture with a look at the past?

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Americans were receptive to new thinking and new types of mental health practices.

Generally, a human rights movement overtook the country and, of course, larger parts of the world. Ecologism, conservationism, vegetarianism, veganism all arose and grabbed the public's attention. Of course, there was also holism and novel types of psychotherapies.

These ideas were of course accompanied by growing anti-war sentiments, civil and women’s rights campaigns, and—as some psychologists suggested—widespread uncertainty about the future. The famous psychologist Abraham Maslow, who came up with the hierarchy of needs, argued that Americans were adrift in a post-modern world: “We’re stuck now in our own culture…stuck in a silly world which makes all sorts of unnecessary problems.”

Different Means, Same End

Yoga and psychedelics grew together and were interwoven against this broader backdrop. And 1968-1969 was certainly a significant time. To be sure, so much was happening 50 years ago in the realm of anti-psychiatry, diagnostics, and the politics of mind and drugs.

During these tumultuous times, some Americans saw yoga and psychedelic drugs as appropriate routes to spiritual fulfillment and mental health. As the San Francisco Oracle put it in 1965: “Yoga and psychedelics. Different means, same end.”

Indeed, some Americans felt that tripping out and artful poses led to new perspectives on the mundane. New ways of seeing the world and one's self within it.

Eastern religion, experimentation with yoga, and psychedelics all seemed to be legitimate alternatives to dealing with the fractures in American politics and society. Experimentation—with LSD or with yoga mats—also seemed a useful substitute for existing mental health strategies.

Contemporaneously, mental health services in the U.S. were being criticized to a greater degree. R.D. Laing and Thomas Szasz, for instance, questioned psychiatric practice and thinking. Others, too, felt that “American psychiatry seems to be in a state of confusion” and psychiatrists themselves had become ever more “skeptical.” People were looking for answers, for transformation.

A mixture of yoga and psychedelics proved to be a solution for some.

Tripping & Posing

Psychedelics, between the 1940s and 1970s, seemed like the next frontier in psychiatry and self-awareness. Research and experimentation flourished, as I wrote last week. LSD, in particular, “spawned a global interest in the cross-cultural dimensions of hallucinogens.” Many researchers working in the mental health field expected to generate a “wonder drug.”

When it came to the fusion of psychedelics and yoga, though, various personalities and organizations drove the relationship.

For instance, in 1962 the famous Esalen Institute, near Big Sur, California, was founded by Stanford graduates Michael Murphy and Richard Price. Murphy was apparently inspired to found Esalen by Sri Aurobindo, an Indian philosopher and yogi.

Similarly, Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass) embarked on a transformative trip to India, and he explored Hinduism, Buddhism, meditation, and yoga. He combined these ideas with his psychedelic research, investigating the crossover points with drug and spirituality. Alpert regarded psychedelics, especially LSD, as a “sacrament” of the countercultural movement.

Finally, there was Stanislav Grof, a psychiatrist, psychedelic researcher, and one-time scholar at the Esalen Institute. In a feature piece for Yoga Journal in 1985, Grof recalled how he had mined Eastern thinking to supplement orthodox medical therapies.

***

Commentators and mental health professionals weren't all supportive. Push back to the blending of yoga and drugs revolved around arguments about the cultural appropriation of Eastern spiritual language and metaphors.

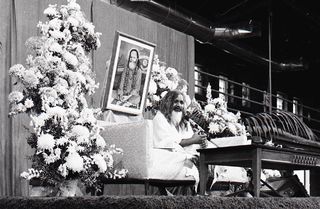

During the 1960s-1970s, several yogis toured the U.S., such as Maharishi Maresh below, with the purpose of participating in academic and public conferences. Maresh was part of an even called "The Science of Creative Intelligence."

And some of these yoga gurus with “large American followings” regularly “dismissed psychedelics…and frowned on any mingling of drugs and discipline.”

Why? Indian yogis had long valued altered states of consciousness. But some felt that drug-related experiences had the potential to be trivial regarding dharma. Worse yet, the trips might even be dangerous. Meher Baba, a Sufi spiritual teacher in India, was a noteworthy opponent of yoga/psychedelic practices.

In 1966, Baba penned the antipsychedelic article “God in a Pill?” and described LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin-fueled “spiritual” experiences as “superficial.” He wrote that psychedelics were “positively harmful” for the spirit. And he argued that such substances should only be used “when prescribed by a professional medical practitioner.”

**

Seeing the psychedelic researcher Stanislav Grof in Yoga Journal wasn’t surprising. Other mental health professionals featured in its pages, too, including Arthur Janov (creator of Primal Scream Therapy), Abraham Maslow (mentioned earlier), and R.D. Laing.

And by the early 1990s, Yoga Journal published a series of retrospective articles on the 1960s and the search for altered states of consciousness. Psychedelics immediately jumped off the page, and this reflected the deeply embedded role such substances had in American yoga culture. This was yoga's leading journal, after all.

One article relayed how the trippers and yogis of the 1960s-1970s had rediscovered “ancient knowledge about the potentials of the human mind.” Americans’ journey deep into Eastern religion was an attempt to break the “consensus trance” that dominated “normal” life. And the meeting of psychedelics and yoga was simply a natural reaction.

Good Openness

Eastern and countercultural ideas about health, religion, and freedom challenged mainstream thinking in the 1960s and afterward. Radical therapies, psychedelic drugs, and ancient practices like yoga and meditation, promoted by Indian gurus and Western academics, became important elements of American spiritual and cultural life.

It was a transformative period, to be sure. And even if the more grandiose designs of the countercultural movement were not realized, the U.S. opened up as a result of the radicalism and experimentation. “Some of it is flaky openness, being open to nonsense,” one commentator put it, “but a lot of it is a good openness.”

Finally, health outcomes have definitely influenced the rise of yoga in the U.S. Linked to many health benefits, yoga purportedly enhances the mind and body. Doctors have prescribed it, clinical psychologists use it for depression, and a variety of organizations use it for economic, learning, and healthcare purposes. Ashtanga, Bikram, Hatha, Iyengar, and Vinyasa have become household terms for many yoga mat-carrying Americans.

But spirituality has driven yoga's growth as well. It's a growth linked to psychedelics and the counterculture some 50 years ago—and from the early years of psychedelic research to the YouTube gurus of the 2010s, Americans have sought spiritual sustenance by dropping onto yoga mats and, to a lesser extent, dropping acid.

(An earlier version of this article was published with Matthew Decloedt in The Psychologist)

References

Daniel Bell, “Religion in the Sixties,” Social Research 38, no. 3 (1971), 488-489.

Edward Hoffman, “Abraham Maslow, Transpersonal Pioneer,” Yoga Journal 81, July/August 1988, 107.

Douglas Osto, Altered States: Buddhism and Psychedelic Spirituality in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

Thomas Robbins, “Eastern Mysticism and the Resocialization of Drug Users: The Meher Baba Cult,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 8, no. 2 (1969), 310 (308-317).

Lawrence Samuel, Shrink: A Cultural History of Psychoanalysis in America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013).

Ben Sessa, The Psychedelic Renaissance: Reassessing the Role of Psychedelic Drugs in 21st Century Psychiatry and Society (London: Muswell Hill Press, 2012).

Stefanie Syman, The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

Wilson Van Dusen, “LSD and the Enlightenment of Zen,” Psychologia 4 (1961), 15 (11-16).