Child Development

It’s All Bawls: Coping with Inconsolable Infants

Exploring the scientific background to baby colic

Posted January 22, 2019

Years ago, an Oxford colleague invited me home for dinner together with his wife and baby. We dined early because he had an unusual task after nightfall. The infant had excessive crying attacks and the best way of taming this was running with the buggy through the city streets. This challenge confronts up to one in four new parents. The medical term is infantile colic, but I personally prefer the stronger label paroxysmal fussing.

Excessive crying is nerve-wracking for parents, and desperate frustration may end in shaken baby syndrome, the main cause of abusive head trauma (AHT). Fortunately, this is rare, estimated at 3-4 cases per 10,000 babies in the USA. Strikingly, a 2016 analysis by Joanne Klevens and colleagues revealed that, after paid family leave became mandatory in California in 2004, AHT was much lower than in states without this provision.

What is baby colic?

Succinctly defined, infantile colic is excessive crying of an otherwise healthy baby not due to hunger. The name, connected with the colon (large intestine), reflects the traditional view that indigestion-related lower belly pain is responsible. A colicky baby does not stop crying when picked up. It typically pulls up its legs, while gas and fluids moving in the gut produce gurgling noises — borborygmus.

Two seminal reviews, both published in 1954, reviewed “three months’ colic” (Ronald Illingworth) or "paroxysmal fussing" (Morris Wessel and colleagues). Together, they underpinned the Rule of Three: crying over three hours a day, more than three days a week, longer than three weeks. Many later investigators followed this definition. Illingworth reported that in 90% of affected babies colic began by two weeks after birth, ceasing on average at nine weeks.

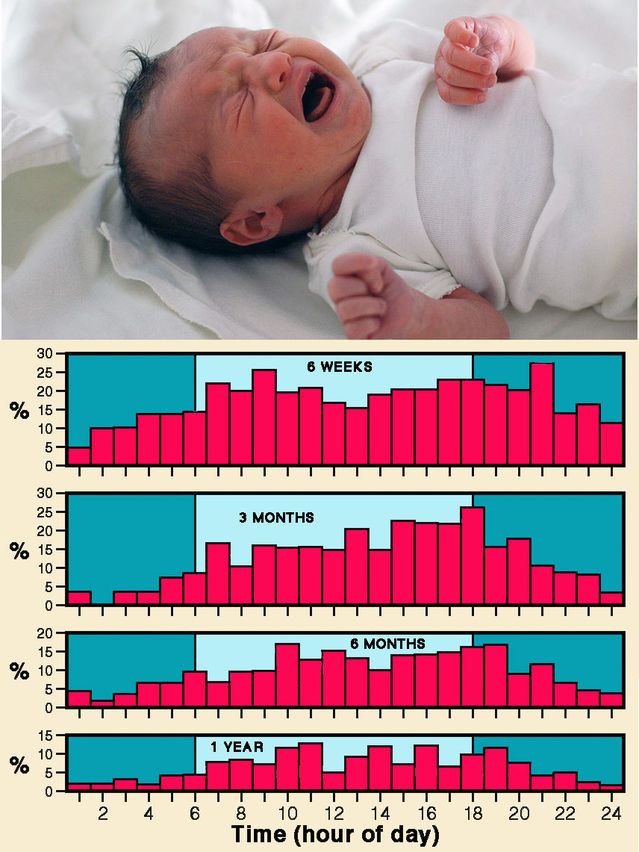

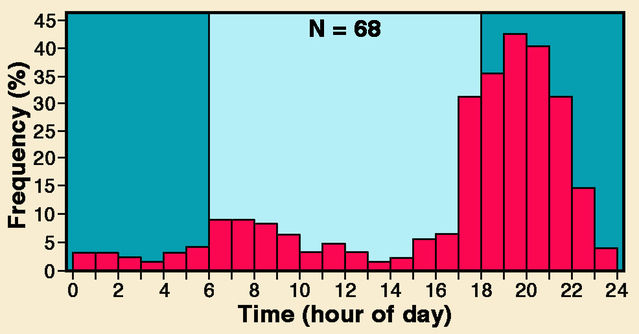

Wessels and colleagues noted a regular crying peak for “fussy” infants between 7:00 and 8:00 p.m., now accepted as characteristic. A lesser crying peak 12 hours earlier suggests some connection with the 24-hour body clock (circadian rhythm). Thirty years after his 1954 review, Illingworth revisited the topic. He advocated the label “evening colic” and discarded his earlier designation “three months' colic”, which misleadingly implies an onset at three months.

One might expect that caregivers find distinctive features of colicky crying particularly upsetting. However, in 1999 Ian St James-Roberts compared the most intense segments of colicky crying bouts with equivalent parts of pre-feeding hunger cries, to determine whether they differ acoustically. Colic cries did not have a higher pitch or a greater proportion of turbulent noise (dysphonation) — features associated with certain well-defined pathologies. St James-Roberts concluded that colic cries simply “convey diffuse acoustic and audible information that a baby is highly aroused or distressed”.

What triggers baby colic?

Many reasons for infantile colic have been suggested, and multiple factors are probably involved. Illingworth’s 1954 paper compared fifty infants with colic and fifty without. Mothers of the two groups did not differ in age, previous pregnancy history or behaviour. Moreover, babies showed no differences regarding sex, birth weight, allergy, regurgitation, stools or weight gain. Illingworth also emphasized that colic is unrelated to feeding or swallowed air. X-rays taken during a colic attack showed no excess gas in the bowel, so the most likely explanation is some local obstruction to gas flow.

Wessel and colleagues similarly reported that "fussy" and "contented" babies did not differ regarding birth weight, feeding, weight gain, sex, or mother’s educational level. They identified family tension as an important contributing cause for almost half the fussy infants and noted some indications of allergy.

Lessons from crying in other mammals

Shedding tears while crying is uniquely human, but babies of non-human primates and other mammals do utter recognizable distress calls. With various monkeys and apes, infants experimentally separated from mothers utter strident isolation calls. And this raises a key question: Might crying betray a baby’s presence to predators? I remember discussing with a London colleague whether our distant ancestors’ babies could cry often and lustily without attracting predators. He had considered this and concluded that a caregiver’s natural response would be to pick up the infant and flee. When he tried picking up his own crying baby and running, it worked!

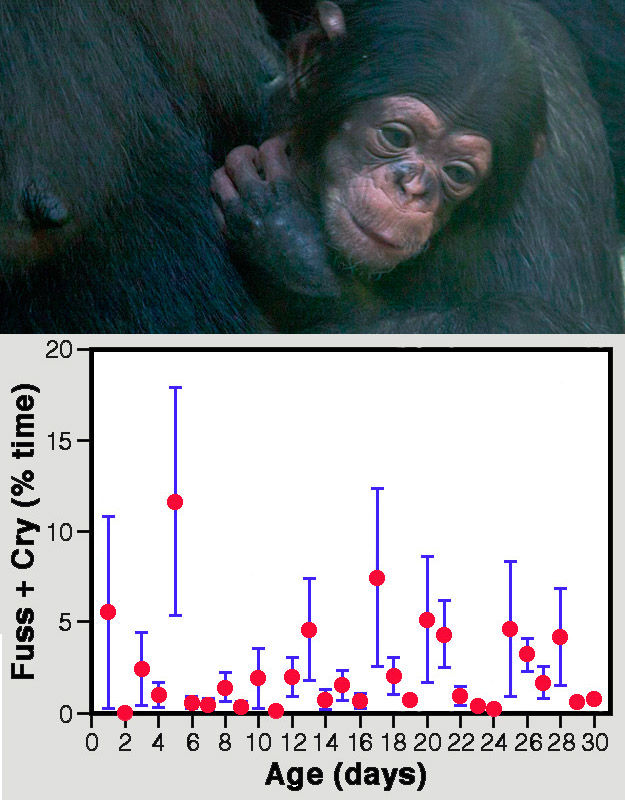

A 2000 book chapter by Kim Bard (whose own son showed “bouts of inconsolable crying from 6 to 18 weeks of age") provided detailed information on infant crying in our closest primate relatives, chimpanzees. Her extensive observations of chimpanzees at Emory University’s Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center revealed that infants emit distinctive vocalizations when upset or frightened. Fussy hoo calls, accompanied by a whimper face, indicate moderate distress; severe distress triggers actual crying with a scream face. Hour-long observation sessions of six mother-reared baby chimpanzees during their first month indicated totals of about a minute for fussiness and under four seconds for actual crying. Colicky crying is exceedingly rare in chimpanzees.

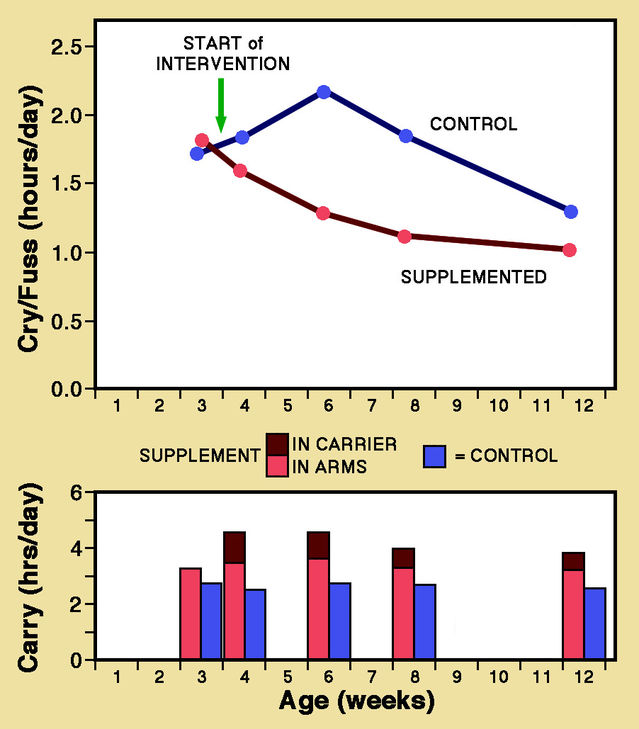

Carrying young babies clinging to the mother’s body is a striking feature of most non-human primates. Bard reported that in baby chimpanzees extended crying is essentially restricted to separation from the caregiver. Once an infant is picked up, crying stops almost immediately. A randomized controlled trial with human babies reported by Urs Hunziker and Ronald Barr in 1986 was designed to test whether "normal" crying could be reduced by extra carrying in addition to routine feeding and calming. They divided 99 mother-infant pairs into two groups, one with increased carrying (in a sling or the mother’s arms) and the other serving as a control. At the peak crying age of 6 weeks, fussing and crying were halved for infants with supplementary carrying. Similar but smaller decreases were seen at 4, 8, and 12 weeks. Hunziker and Barr concluded: “The relative lack of carrying in our society may predispose to crying and colic in normal infants.”

Treatment of baby colic

A convincing explanation for colic remains elusive, so treatment has understandably been haphazard. Gripe water — a purported remedy launched in 1851 — is still available today without prescription worldwide, despite a complete lack of evidence for benefits. William Woodward’s original formula contained alcohol, sugar, sodium bicarbonate and dill oil. But the USA banned alcohol and sugar from gripe water in 1982. (Reportedly, many parents took to swigging gripe water themselves, often becoming addicts.) Nowadays, most gripe water is alcohol-free and sugar has generally been replaced by artificial sweeteners.

Ideally, randomized controlled trials are needed to assess the effectiveness of any anti-colic treatment. But few have been conducted, least of all with gripe water. Several reviews have identified little support for most “cures”. However, one recent development does raise encouraging prospects for an effective treatment.

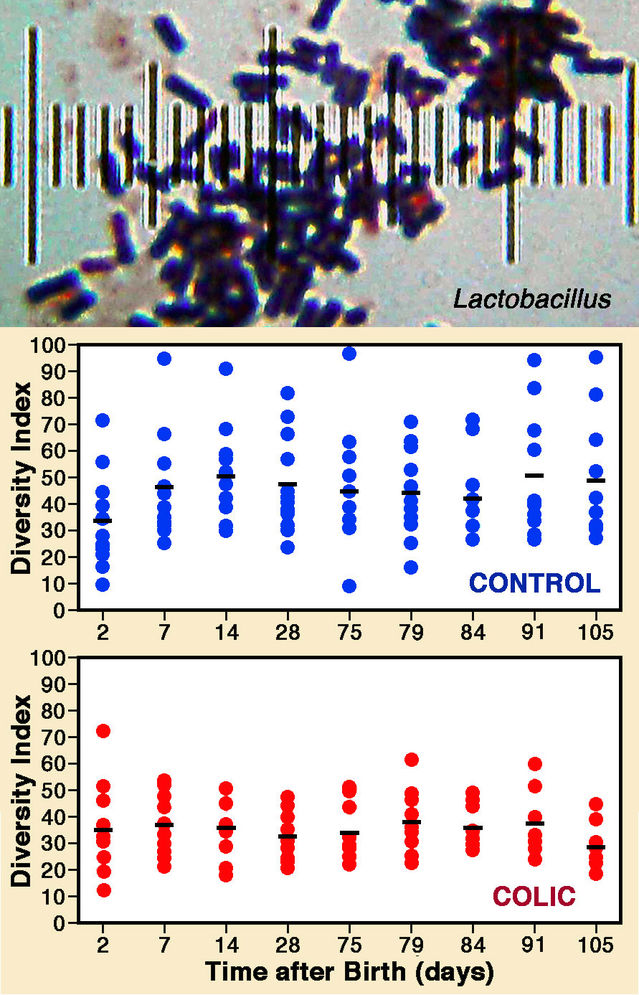

Microbes inhabiting the human digestive tract (the gut biome) have recently attracted much attention and considerable evidence indicates that imbalances have far-reaching health consequences. Accordingly, a 2013 paper by Carolina de Weerth and colleagues reported indications that colic is possibly connected with gut microbes. Fecal samples from twelve colicky infants were compared with samples from a dozen age-matched, colic-free infants during their first three months. Crucially, it emerged that fecal microbes became steadily more diverse in control infants but not in the colicky babies. Further analyses revealed that potentially noxious proteobacteria were more than twice as prevalent in colicky infants, whereas beneficial kinds were significantly reduced. This raises prospects for early diagnosis and treatments, with positive initial results already reported from treatment trials with Lactobacillus. Imbalance in the gut biome is not easily corrected, which may explain the failure of previous treatments designed to combat specific gut ailments. Resident microbes may well underlie the long-suspected connection between colic and the digestive tract.

References

Baildam, E.M., Hillier, V.F., Ward, B.S., Bannister, R.P., Bamford, F.N. & Moore, W.M. (1995) Duration and pattern of crying in the first year of life. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 37:345-353.

Bard, K.A. (2000) Crying in infant primates: Insights into the development of crying in chimpanzees. pp. 157-175 in: Crying as a Sign, a Symptom, & a Signal: Clinical, Emotional and Developmental Aspects of Infant and Toddler Crying. (eds. Barr, R.G., Hopkins, B. & Green, J.A.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

de Weerth, C., Fuentes, S., Puylaert, P. & de Vos, W.M. (2013) Intestinal microbiota of infants with colic: Development and specific signatures. Pediatrics peds.2012-1449:e550-e558.

Gelfand, A.A. (2016) Infant colic. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology 23:79-82.

Hunziker, U.A. & Barr, R. (1986) Increased carrying reduces infant crying: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 77:641-648.

Illingworth, R.S. (1954) Three months' colic. Archives of Disease in Childhood 29:165-174.

Illingworth, R.S. (1985) Infantile colic revisited. Archives of Disease in Childhood 60:981-985.

Johnson, J.D., Cocker, K. & Chang, E. (2015) Infantile colic: recognition and treatment. American Family Physician 92:577-582.

Long, T. (2008) Excessive Crying in Infancy. New York: John Wiley.

Roberts, D.M., Ostapchuk, M. & O'Brien, J.G. (2004) Infantile colic. American Family Physician 70:735-740.

St James-Roberts, I. (1999) What is distinct about infants' 'colic' cries? Archives of Disease in Childhood 80:56-62.

Wessel, M.A., Cobb, J.C., Jackson, E.B., Harris, G.S. & Detwiler, A.C. (1954) Paroxysmal fussing in infancy, sometimes called colic. Pediatrics 14:421-435.