Infidelity

3 Ways People Try to Keep Partners from Cheating, or Leaving

A new study identifies three common clusters of mate-retention tactics.

Posted November 16, 2019 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Having one partner, also called monogamous mating, can be beneficial to both men and women from an evolutionary perspective: Men who are in monogamous relationships need not worry about raising another man’s child, and women need not worry about their partner being invested in other women and their children.

But what happens if one partner cheats or suddenly leaves the relationship? This can be highly costly, which is why both members of a monogamous relationship engage in mate retention strategies.

Mate retention strategies refer to behaviors, such as buying gifts, intended to reduce the likelihood of infidelity or a breakup. A recent study, published in the September issue of the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, has identified three clusters of mate retention behaviors.1

Negative and positive mate-retention strategies

Before discussing the results of the study, we need to understand the difference between the two types of tactics aimed at reducing the risk of one’s partner cheating or leaving the relationship.

One group of tactics called benefit-provisioning are low-risk approaches that emphasize the positive aspects of the relationship.

Examples of these tactics include showing affection (e.g., giving gifts, complimenting the person’s appearance) and providing various types of support (e.g., financial support; love and care during illness).

The logic behind the benefit-provisioning strategy is this: The other person in the relationship would be less likely to think about cheating or breaking up unless they are willing to lose a lot of benefits.

The second group of tactics, called cost-inflicting, are high-risk behaviors that make it costly for a partner to leave the relationship. These behaviors include the use of deception, intimidation, threats, and other negative behaviors.

For instance, a woman who fears that her boyfriend might cheat on her may mock and ridicule him in front of others so he appears less desirable to potential mates. Or a man who fears his wife will leave him might tell her that he will kill himself if she ever leaves him.

So, are couples more likely to use the first, second, or both mate-retention tactics? The study reviewed below tries to answer this question.

Three clusters of mate-retention strategies

The sample included 697 participants (56% men) who had been in relationships with the opposite sex for three months or longer. Participants were on average 29 years old (with a range of 18-70 years). The average relationship length was about six and a half years.1

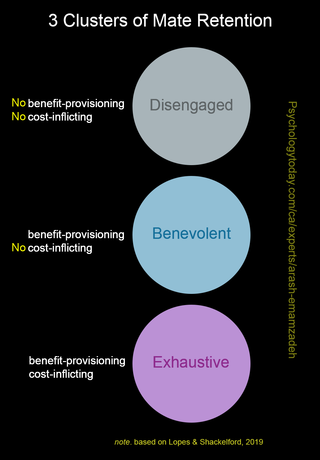

Using a statistical method called cluster analysis, the study’s authors, Lopes and Shackelford, identified three clusters of mate retention strategies in the sample: disengaged, benevolent, and exhaustive.1

Disengaged mate-retention

Participants in the disengaged cluster rarely performed either benefit-provisioning or cost-inflicting behaviors. Why? One reason might be that they believed their romantic partners were unlikely to be unfaithful.

Such beliefs may be more common in committed relationships like marriages. Previous research has shown that mate retention behaviors gradually decrease post-marriage, perhaps because couples feel they can trust each other enough by then.2

People who feel emotionally detached may also utilize this strategy. This is consistent with this study’s finding that those in this cluster (compared to other clusters) were less likely to be physically intimate with their partner.1

Benevolent mate-retention

Participants in the second group, labeled benevolent cluster, regularly used only benefit-provisioning approaches; they rarely used any cost-inflicting ones.

Benevolent mate-retention is more often used by those who have high levels of self-esteem and relationship satisfaction. Those who value the relationship—but do not fear infidelity—also employ this strategy frequently.

Exhaustive mate-retention

The third cluster, labeled exhaustive, was populated by participants who used both benefit-provisioning and cost-inflicting approaches.

These individuals might have added the cost-inflicting behaviors later—only when the risk of infidelity seemed high (or infidelity seemed very costly) to them.

Individuals who employ this approach appear to be less intimate with their partners. Another group inclined to use exhausting approaches are people with children. Why? Perhaps because the “diversion of a partner’s investment is reproductively costly for a woman and her offspring...and a partner’s defection may be especially costly for a man who has invested resources in the offspring.”1

Concluding thoughts on mate retention

The study examined here found three clusters of mate-retention behaviors: disengaged (no benefit-provisioning or cost-inflicting), benevolent (benefit-provisioning but no cost-inflicting), and exhaustive (both benefit-provisioning and cost-inflicting). This is demonstrated in the figure above.

The choice of mate retention tactics depends on many factors, including a person’s self-esteem and resources. When people do not have enough resources (e.g., time, money), they are more likely to resort to using cost-infliction or a disengaged approach. Gender can also make a difference. In the study reviewed today, men employed benevolent mate retention strategies more frequently, while women used disengaged mate retention strategies more often.

Facebook image: Simone van den Berg/Shutterstock

References

1. Lopes, G. S., & Shackelford, T. K. (2019). Disengaged, exhaustive, benevolent: Three distinct strategies of mate retention. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(9), 2677–2692.

2. Kaighobadi, F., Shackelford, T. K., & Buss, D. M. (2010). Spousal mate retention in the newlywed year and three years later. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 414–418.