Stress

COVID Stress Syndrome: What It Is and Why It Matters

Emerging research defines a unique pandemic-related constellation.

Posted July 11, 2020 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Pandemics are unlike other disasters due to their broad scope and prolonged, fluctuating timeline. COVID-19 (caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus) is shaping up to be unlike prior coronavirus infections, impacting multiple organ systems, not just the lungs, causing widespread problems related to blood clotting abnormalities and inflammatory reactions.

In particular, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier, resulting in myriad neuropsychiatric problems ranging from depression and anxiety to psychotic reactions to delirium and cerebrovascular accidents (strokes) to chronic executive dysfunction. The mental health impact of COVID-19 is of increasing concern. In addition to the direct effects on the brain, the COVID-19 pandemic is causing unprecedented psychological distress, threatening a “crashing wave” of mental health problems.

Given the uniqueness of COVID-19, conventional ways of describing the psychiatric impact, while relevant, are not complete. Contributory constructs such as PTSD, Acute Stress Reaction, Major Depression, Adjustment Disorder, Anxiety Disorders do not fully capture all the dimensions of this pandemic.

The COVID Stress Scale and Syndrome

Researchers Steven Tayor, Caeleigh Landry, Michelle Pluszek, Thomas Fergus, Dean McKay and Gordon Asmundson previously developed a model of “COVID Stress Syndrome” (CSS, 2020), identifying five distinct yet interrelated elements:

- DAN: Fear of danger from COVID-19 and getting infected by different means e.g. touching contaminated objects, breathing contaminated air.

- SEC: Worry about the social and financial impact (socioeconomic costs) of the virus.

- XEN: Marked concern that foreigners spread the disease.

- TSS: Related symptoms of traumatic stress.

- CHE: Compulsive checking and seeking reassurance.

In the current study (2020), the original work was extended to look at important correlations of CSS with demographic factors, depression, anxiety, and other important measures.

Using an online approach at the end of March 2020, researchers surveyed a diverse group of 6,854 adults whose average age was 49.8 years from the US and Canada, who completed the following measures:

- Demographics, including having been infected and knowing people who were infected

- Patient Health Questionnaire-4

- Short Health Anxiety Inventory

- Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3

- Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12

- Perceived Vulnerability to Disease Scale

- Disgust Propensity and Sensitivity Scale-Revised

- Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory

- COVID Stress Scales: Looking at belief in COVID conspiracy theories, COVID-related avoidant behaviors, hygiene behaviors, and stockpiling/panic-buying.

- Measures of self-isolation and related factors (emotions, financial stress, etc.), and isolation-related coping strategies.

Findings

First, only 2 percent reported having been diagnosed with COVID-19, and only 6 percent knew someone diagnosed. Four percent were healthcare workers. By contrast, rates of anxiety and depression were disproportionately elevated. Twenty-eight percent of the group reported clinically significant anxiety and 22 percent depression.

At the time, 12 percent reported facemask use, nearly 90 percent regular hand-washing, nearly 60 percent regular hand sanitizer use, 95 percent social distancing, and 48 percent self-isolating.

There were five groups (“classes”) of severity on the CSS, ranging from little or no distress to severe distress: Class 1 (3 percent), Class 2 (11 percent), Class 3 (32 percent), Class 4 (38 percent), Class 5 (16 percent).

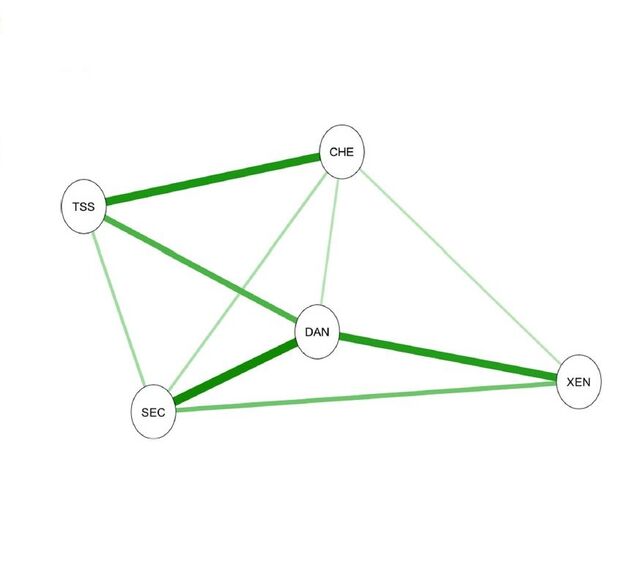

Using “network analysis” to look at how the five CSS factors were related (see diagram below), researchers found that the DAN factor was the most “central,” tying the other factors together, with the strongest links to SEC and XEN. SEC was the second most central node, highlighting the core importance of feeling unsafe regarding both physical and emotional well-being and social and financial security. Overall XEN and CHE were the weakest nodes. However, TSS and CHE were correlated, showing the relationship between traumatic stress and checking behavior and reassurance seeking.

Demographically, there were no differences reported between US and Canadian populations. Younger people were slightly more concerned, and more well-off people slightly less. Women had higher CSS scores, as did less educated or unemployed respondents. In terms of ethnicity, CSS scores were lowest for Caucasians, in the middle for Black/African Americans, and highest for Asian and Hispanic respondents.

People diagnosed with COVID-19 had higher CSS, but (in this study) people in higher-risk groups (healthcare workers, essential workers) did not have different CSS. Prior medical conditions did not correlate with high CSS scores, but those with pre-existing mental health conditions did. High levels of anxiety, lower tolerance of uncertainty, sensitivity to anxiety, vulnerability to disgust, and related concerns about contamination and checking were associated with higher CSS.

High CSS was associated with then-current elevated anxiety and depression, belief in conspiracy theories, increased hygienic behavior, stockpiling food and related supplies, avoiding public places, and face mask use.

Self-Isolation and CSS

About half of the sample reported self-isolation, on average for 10 days. Due to varying recommendations at the time, so were following public health guidelines, and others were voluntarily isolating. CSS had a small correlation with time spent in isolation, but those with higher CSS scores were more likely to report more severe distress during isolation. Those high on CSS reported more problems during isolation, including problems with prescription access, interpersonal issues, concerns about care of pets or family, money problems, and lack of space. Living alone was correlated with lower CSS scores, on average.

People with high CSS explored a greater variety of coping strategies, actively seeking relief. Strategies including adaptive and maladaptive approaches, for example setting routines and social connecting versus overeating and substance use. The most common strategies included watching videos, cleaning and tidying, keeping social contact with friends and family, and remembering that quarantine was altruistic.

People high in CSS were the least likely to access healthcare, either mental or physical. Interestingly, CSS score was not correlated with perceived efficacy of different coping strategies, but people with high CSS were prone to use “emotion-focused” coping like over-eating to reduce distress temporarily, and seek help from a physician or therapist.

Further considerations

The results of this study support the validity of the COVID Stress Scale for understanding responses to this pandemic, and further refinement will show whether this construct is valid in future pandemics, and if it constitutes a useful diagnostic framework. CSS bridges several different psychiatric constructs to define an arguably unique constellation.

Balance here comes from rational assessment of risk in order to put proportional measures in place. Assessing risk is complicated by a lack of clear leadership, conflicting messages, evolving factual information, and personal factors such as anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty as well as pre-existing mental health conditions.

It would be interesting for future research to look at correlates with CSS and measures of resilience and post traumatic growth. Research on personality, coping, and creativity suggests that there are three different personality profiles associated with how well one does with COVID-19 lockdown.

Foresight and the Future

The CSS stands to be a useful tool for tracking different phases of this pandemic. Findings from the current study, sampled in March of 2020, are likely to change over time. It will be useful to understand whether vulnerability and coping change with the duration of the pandemic for different groups.

Thoughtful research provides quality data to reduce uncertainty and guide constructive, collaborative, and informed decision-making. Those in leadership positions can best serve constituents by restoring and preserving the public good, while educated constituents are the most effective advocates for necessary changes in leadership and policy.

Interested in post traumatic growth during COVID? Take this academic research survey and contribute to science.

References

An ExperiMentations Blog Post ("Our Blog Post") is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. We will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by your reliance on information obtained through Our Blog Post. Please seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding the evaluation of any specific information, opinion, advice, or other content. We are not responsible and will not be held liable for third party comments on Our Blog Post. Any user comment on Our Blog Post that in our sole discretion restricts or inhibits any other user from using or enjoying Our Blog Post is prohibited and may be reported to Sussex Publishers/Psychology Today. Grant H. Brenner. All rights reserved.