Genetics

Genetics and the Ides of March

How seasons and genes affect major psychiatric symptoms

Posted March 19, 2015

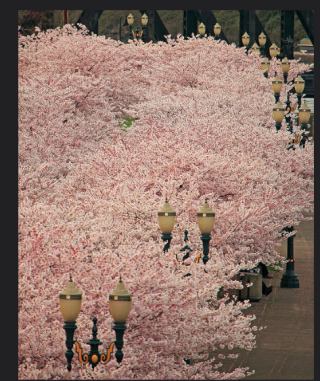

Many will find it surprising that late winter and early spring are the busiest time in psychiatry, followed closely by early fall. Forgive the generalizations, but in the deep winter, folks tend to get depressed, but tend to cocoon themselves away. In the high summer, people tend to be steady, energetic but relaxed, productive, and happy. The transitions between these two states are the rough part when the phone starts to ring off the hook and a lot of people really struggle to keep it together. We all know people who adore the deep winter and loathe summer, or those who thrive in fall or can’t get enough of tulips and bunnies and springtime. The general pattern of spring being tough is for the population, not every individual. The sunlight (or lack of) can be an issue, but it is the rapid change in the duration and strength of sunlight that occurs in spring and fall that seems to be the hardest part.

Around the office we say “beware the Ides of March.” In ancient Rome, the year began with spring, not in the middle of winter, and the Ides of March (the Ides being halfway through the month in the Roman calendar) corresponded to the first full moon of the year. The Ides of March used to be a celebration of the springtime, but became famous for the date when Julius Ceasar was assassinated in 44 BC. The difficulty of this time of year in mental health, however, has nothing to do with the moon, but rather the rapid increase in sunlight. It’s brighter, bringing energy and motivation, but the cold and dragginess of winter aren’t quite gone, so the extra sunlight seems to lead to irritability, insomnia, and an increase in the suicide rate (1). Sunlight can have a direct effect on the mood via the retina and signals to the major clock system of the brain, the hypothalamus, and vitamin D levels also shift with the seasons and may be a component of the psychiatric changes we tend to see.

People with variations of bipolar disorder are particularly vulnerable to the insomnia and light changes of spring leading to irritability or even mania. Other folks who have a seasonal-type depression struggle more in the fall, and they begin to feel much better by the Ides of March. In a recent article in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, researchers have tried to figure out if the seasonal components of mental illness are genetic.

In order to do this, researchers used some different populations, including the Amish in Pennsylvania and twins in Australia. Scientists collected genomes and had the subjects answer questions about psychiatric diagnosis, mood, and how the seasons affect symptoms. Then the researchers did a genome wide association study, or a brute force hack of the genome, looking for genetic segments that are shared between people who have bipolar disorder, for example, and a seasonal component to symptoms.

Turns out there are some genes that seem to code for a risk for psychiatric illness with a genetic component. Not surprisingly, bipolar disorder with a seasonal component does seem to be inherited (though no single specific gene came out… a combination of certain genes fall together to increase risk, as with many psychiatric disorders). Bipolar disorder is easy to link to springtime and other seasonal changes. More energy, more light, insomnia…mania or mixed states just waiting to happen. Way more surprising was the finding that folks with schizophrenia also had a seasonal pattern to symptoms that was inherited. It’s not widely known, but first break psychosis in schizophrenia has been shown to have a seasonal component, while in Alaska, researchers noticed that schizophrenics were more likely to have mood changes associated with seasons. Another surprising finding is that major depressive disorder really didn’t have an inherited seasonal component, reinforcing the idea that seasonal affective disorder is more closely related to bipolar disorder than to depression.

The research has some limitations. For one, the use of an isolated genetic population like the Amish has a higher probability of finding genetic linkages that won’t be applicable to the general public. However, these genes can give us clues as to how season and light and even Vitamin D might affect mood and psychiatric illness. It can also give us clues to low risk novel treatments that might help symptoms, such as vitamin D supplementation, light therapy, and blue blocking glasses to manage light input and improve sleep cycles during all seasons.

Image credit: private instagram account, flickr creative commons

Copyright Emily Deans MD