Environment

Did Dogs Help Hunters Succeed?

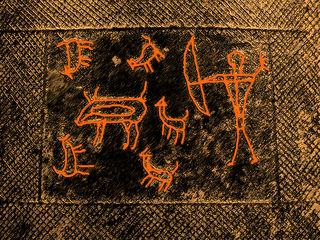

Early Japanese people used dogs to hunt deer and wild boar.

Posted September 25, 2016

The Jōmon culture of hunters and foragers dominated the Japanese Archipelago for more than 10,000 years from the end of the Last Glacial Maximum to the arrival around 2400 years ago of agriculturalists, who supplanted them. A mosaic of a number of subcultures adapted to their local conditions, Jōmon is named for its pottery—made by pressing cords into wet clay—which is among the oldest in the world. It is also known for its bone, antler, polished stone, and shell figurines, arrowheads, spear points and tools. Today, like a number of other cultures, including several in the new word, it is ready proof that agriculture is not a necessary foundation for a complex, stable, society.

As the earth warmed and the ice sheets retreated, the Jōmon occupied islands stretching from the subarctic to the subtropics. Vegetation changed and came to be dominated by the polar tundra and conifer forests of the subarctic northern island of Hokkaido, the temperate deciduous forests of Honshu, and the warm evergreen forests of Shikoku and Kyushu islands. People’s food choices differed by region as well, with people from Hokkaido and northern Honshu relying primarily on marine mammals and fish and those from southwestern Honshu south through Kyushu living on fish and shellfish and plant material. The people of north central Honshu ate terrestrial mammals and other foods from the forest in addition to the fruit of the sea. In short they had the most varied diet in the archipelago.

The varied diet of the Pacific Honshu Jōmon, as they are known because they occupied the eastern, Pacific side of the island, included sika deer and wild boar. They were among the ungulates that had replaced the Ice Age megafauna, including Naumann’s elephants, giant elk, steppe bison, aurochs, and Yabe’s giant deer, which had roamed the archipelago through the Last Glacial Maximum and then vanished in the Quaternary Extinction Event that marked the end of the Pleistocene. Whether human hunters were responsible for or contributed disproportionately to that great dying is a matter for debate except among those ideologues who unequivocally believe that humans were responsible for the extinction of some 200 species of megafauna—animals weighing more than 44 kilograms—worldwide.

But for some 10,000 years, hunters from this central group of Jōmon successfully supplemented their diets with sika deer and wild boar that they hunted with new kinds of arrowheads and dogs—the most useful tool in their kit because of their ability to locate, track, hold at bay, and retrieve game. That is the conclusion of Angela R. Perri, a zooarchaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. She presented the conclusions drawn from a study of 110 dog burials from 39 sites in an article published September 16 in the online edition of the journal Antiquity. Each burial was isolated and deliberate, with some of the dogs showing signs of broken bones that had healed but no sign of human-induced injury, Perri says. Others appeared to have been put into restful positions. The healed bones, like, the burials themselves were expressions of the esteem in which the animals were held. Medium sized, the dogs resemble the current shiba inu.

Perri says that the occurrence of burials at the middens of more than one group of Jōmon indicates dogs’ importance in helping people adapt to their environment by exploiting deer, wild boars, and other animals in Honshu’s deciduous forests. Wild boars can inflict considerable damage on humans and dogs; hunting them with spears and bows and arrows and even a pack of experienced dogs requires considerable skill.

The importance Perri ascribes to Jōmon dogs and the nature of the game they were being used to hunt, as well as a time frame of millennia, not centuries would suggest that the number of sites that have been found and excavated represent but a fraction of those that exist. In fact, she argues that the reliance on hunting dogs increased toward the end of the Jōmon period as resources declined and that importance is manifest in the increase in the number of dog burials.

This a fine but limited paper. Its chief strength is that it relies on a variety of evidence, including the documented behavior of hunter and forager groups hunting with dogs, and ties that material to environmental and demographic conditions in Japan to present a solid case for Jōmon dog use. It also makes a convincing case for the value the Jōmon placed on these dogs in recognition of their importance to their survival.

But Perri does not cover many basic questions. Had she chosen to address them, she would have strengthened her paper by expanding its context. Here are a few of those questions: Did Jōmon hunters and their dogs enter the Japanese archipelago before the great glacial melt inundated existing land links? Or were they already there? In any event, the Jōmon would have had early dogs and it is fair to ask where and when they got them? Did they use their dogs for anything other than hunting—guarding and hauling, for example? If they were in Japan before the glacial retreat, did they hunt the megafauna there? If so, did they use dogs? Did the dogs come in more than one size? Did Jōmon in other areas have dogs, and if so for what did they use them? Were hunting dogs given preferential treatment? Agriculture arrived in Japan around 2400 years ago, and with it the practice of slaughtering and eating dogs began. Who were those early agriculturalists and who were their dogs?

Why some cultures ate dogs while others found the practice abhorrent is an interesting question in its own right, one of many yet to be answered.