Sexual Abuse

Male Sexual Assault: The Reckoning That Never Happened

A new film underscores the challenges faced by male victims of sexual abuse.

Posted February 12, 2019

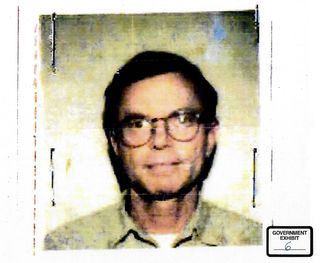

A heartbreaking new film, Predator on the Reservation, exposes a pedophile who abused young men as a pediatrician on Native American reservations for more than 20 years. The investigation reveals the Indian Health Service’s astonishing failure to permanently remove Stanley Weber from his post. But the film also calls attention to the different experiences of men and women who face sexual abuse—and how the #MeToo movement has fallen short in sweeping male victims along in its wave of progress.

“Although we know that women underreport incidents of sexual assault, at least there is a national discussion about it,” says Lisa Dario, an assistant professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Florida Atlantic University. “For young men, there is no national discussion. It’s still taboo.”

Predator on the Reservation, a collaboration between The Wall Street Journal and PBS Frontline that airs tonight, begins on the Blackfeet reservation in Montana. The doctor Stanley Weber arrives, eager to open new clinics and promote children’s health programs in the community. But Weber’s appealing façade belies sinister motives. Weber’s basement is filled with candy, soda, toys, and games, and he constantly invites young boys to his house. Family and community members soon realize that Weber preys on 10- to 15-year-old boys both at the clinic and at his home. A few individuals try to take action, but the Indian Health Service ultimately refuses to fire Weber—instead moving him to the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, where the process inevitably repeats itself.

Paul was a 13-year-old boy who lived in poverty in Pine Ridge. Weber offered him shelter, food, clothing, and money in exchange for sexual favors. “I had nothing and nobody … You do what you have to in order to get by,” Paul says in the film. “Here this guy was offering me money, so I can find a place to sleep. All I had to do was a few f*cked up favors. At the time, it made me feel super f*cked up.” Later, Paul’s shame leads him to collect a few friends, drive to Weber’s house, and beat him up.

Paul’s experience of sexual abuse is one that many men have endured. One in six men will experience sexual violence in their lifetime, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (But sexual violence statistics often underestimate the true prevalence due to underreporting.) Sexual assault occurred before age 18 for 94 percent of male victims, according to a 2009 study of more than 700 men in Virginia. These men were more than three times as likely to be depressed and more than twice as likely to have suicidal thoughts than men who were not sexually abused. Just 15 percent of those men sought treatment.

In general, Dario says, women are more likely to have internalized behaviors, such as problems with self-esteem, cutting, disordered eating, depression, or suicidality. Men are more likely to have externalized behaviors, such as committing theft or lashing out violently, as Paul did against Weber. Similarly, sexual trauma can influence women’s and men’s mindsets differently, says Robert Weiss, a sex and relationships therapist who runs sexual trauma treatment centers. According to Weiss, women tend to have a global perspective, so sexual trauma can change their entire sense of self and relationships; men tend to compartmentalize, so the domains in which they are affected may be more limited to problems with intimacy or vulnerability, for example.

Dario’s recent research challenges these assumptions. A survey of nearly 12,000 American adults revealed that symptoms of depression were equal for men and women who had been sexually abused. The publication elicited a flood of responses, Dario says. “Men emailed me and said, ‘This spoke to me. This terrible thing happened to me, and I didn’t feel comfortable talking about it. I wasn’t sure how often this was happening out there.’”

Men are less likely to report sexual assault and to seek treatment, Dario says, because they face distinct challenges. All victims of sexual violence contend with shame and humiliation, but men may face an extra layer of stigma due to cultural ideas about masculinity. Men may believe they should have been “strong enough” or “manly enough” to fight the predator or avoid the assault, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network. Men also report that a fear of being perceived as gay prevents them from coming forward. The belief that they should have been able to handle the situation often leads men to question who they are, Weiss says. “I think there’s more sense of ownership for men that they should have been able to not have had this happen.”

To target this problem, society needs to erode the shame and stigma surrounding sexual assault, Dario says. One step would be for doctors to ask about sexual assault during routine check-ups. Another would be to devote more resources to connecting men with therapy and medication. A larger goal would be to have a national discussion similar to the #MeToo movement for boys and men.

Actor Terry Crews illustrates the tension between the #MeToo movement and the troubling social norms that influence male victims of sexual assault. After speaking out about his experience of sexual assault, the backlash that ensued evoked the notions about masculinity outlined above. To be sure, women who have spoken out have been targeted as well. Yet more and more women continued to come forward, while Crews is one of few men who have gone public.

“I’ve seen men in entertainment attack Terry Crews and say, ‘How could you not fight it off? You’re this big strong guy. Did you want it?’” Dario says. “It’s easy to see how men who are not famous or rich may not want to discuss this, because they don’t want it to be the one thing that defines them.”

A victim from Blackfeet echoes this sentiment in Predator on the Reservation. During the trial, Weber’s lawyer asked why the victim, Joe Four Horns, did not come forward earlier. “Right now, I don’t want to talk about this. I don’t ever want to talk about that … I got molested as a little kid, man, I don’t want to talk about that,” Four Horns says in the film. “Those pieces of sh*t, those child molesters, they deserve to be in prison.”

In September 2018, Weber was convicted of sexual assault and sentenced to 18 years in prison. He is currently appealing the verdict—while awaiting a second trial for sexual abuse in South Dakota.