Fear

The (Only) 5 Fears We All Share

When we know where they really come from, we can start to control them.

Posted March 22, 2012 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- There are only five basic fears, out of which almost all of our other so-called fears are manufactured.

- These fears include extinction, mutilation, loss of autonomy, separation, and ego death.

- When we let go of the notion of fear as the welling up of evil forces within us and see fear as information, we can think about them consciously.

President Franklin Roosevelt famously asserted, "The only thing we have to fear, is fear itself."

I think he was right: Fear of fear probably causes more problems in our lives than fear itself.

That claim needs a bit of explaining, I know.

Fear has gotten a bad rap. And it's not nearly as complicated as we try to make it. A simple and useful definition of fear is: An anxious feeling, caused by our anticipation

of some imagined event or experience.

Medical experts tell us that the anxious feeling we get when we're afraid is a standardized biological reaction. It's pretty much the same set of body signals, whether we're afraid of getting bitten by a dog, getting turned down for a date, or getting our taxes audited.

Fear, like all other emotions, is basically information. It offers us knowledge and understanding—if we choose to accept it.

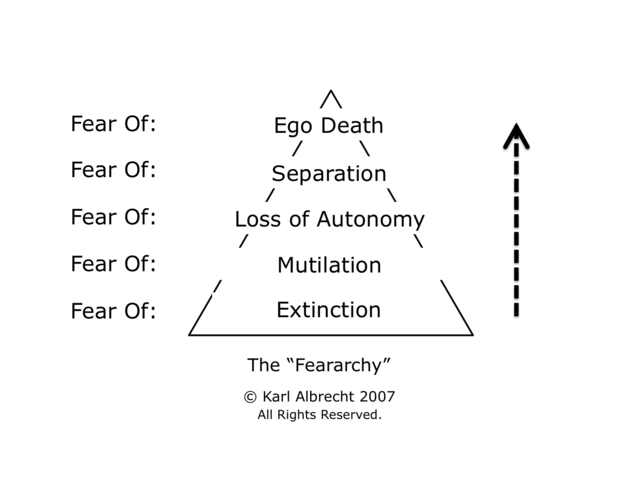

And there are only five basic fears, out of which almost all of our other so-called fears are manufactured. These are:

- Extinction—the fear of annihilation, of ceasing to exist. This is a more fundamental way to express it than just "fear of death." The idea of no longer being arouses a primary existential anxiety in all normal humans. Consider that panicky feeling you get when you look over the edge of a high building.

- Mutilation—the fear of losing any part of our precious bodily structure; the thought of having our body's boundaries invaded, or of losing the integrity of any organ, body part, or natural function. Anxiety about animals, such as bugs, spiders, snakes, and other creepy things arises from fear of mutilation.

- Loss of Autonomy—the fear of being immobilized, paralyzed, restricted, enveloped, overwhelmed, entrapped, imprisoned, smothered, or otherwise controlled by circumstances beyond our control. In physical form, it's commonly known as claustrophobia, but it also extends to our social interactions and relationships.

- Separation—the fear of abandonment, rejection, and loss of connectedness; of becoming a non-person—not wanted, respected, or valued by anyone else. The "silent treatment," when imposed by a group, can have a devastating effect on its target.

- Ego-death—the fear of humiliation, shame, or any other mechanism of profound self-disapproval that threatens the loss of integrity of the self; the fear of the shattering or disintegration of one's constructed sense of lovability, capability, and worthiness.

These can be thought of as forming a simple hierarchy, or "feararchy":

Think about the various common labels we put on our fears. Start with the easy ones: fear of heights or falling is basically the fear of extinction (possibly accompanied by significant mutilation, but that's sort of secondary). Fear of failure? Read it as fear of ego-death. Fear of rejection? That's fear of separation, and probably also fear of ego-death. The terror many people have at the idea of having to speak in public is basically fear of ego-death. Fear of intimacy, or "fear of commitment," is basically fear of losing one's autonomy.

Some other emotions we know by various popular names are just aliases for these primary fears. If you track them down to their most basic levels, the basic fears show through. Jealousy, for example, is an expression of the fear of separation, or devaluation: "She'll value him more than she values me." At its extreme, it can express the fear of ego-death: "I'll be a worthless person." Envy works the same way.

Shame and guilt express the fear of—or the actual condition of—separation and even ego-death. The same is true for embarrassment and humiliation.

Fear is often the base emotion on which anger floats. Oppressed people rage against their oppressors because they fear—or actually experience—loss of autonomy and even ego-death. The destruction of a culture or a religion by an invading occupier may be experienced as a kind of collective ego-death. Those who make us fearful will also make us angry.

Religious bigotry and intolerance may express the fear of ego-death on a cosmic level, and can even extend to existential anxiety: "If my god isn't the right god, or the best god, then I'll be stuck without a god. Without god on my side, I'll be at the mercy of the impersonal forces of the environment. My ticket could be canceled at any moment, without a reason."

Some of our fears, of course, have basic survival value. Others, however, are learned reflexes that can be weakened or re-learned.

That strange idea of "fearing our fears" becomes less strange when we realize that many of our avoidance reactions—turning down an invitation to a party if we tend to be uncomfortable in groups; putting off a doctor's appointment; or not asking for a raise—are instant reflexes that are reactions to the memories of fear. They happen so quickly that we don't actually experience the full effect of the fear. We experience a "micro-fear"—a reaction that's a kind of shorthand code for the real fear. This reflex reaction has the same effect of causing us to evade and avoid as the real fear. This is why it's fairly accurate to say that many of our so-called fear reactions are actually the fears of fears.

When we let go of our notion of fear as the welling up of evil forces within us—the Freudian motif—and begin to see fear and its companion emotions as information, we can think about them consciously. And the more clearly and calmly we can articulate the origins of the fear, the less our fears will frighten us and control us.

References

Albrecht, Karl. "Practical Intelligence: the Art and Science of Common Sense." New York: Wiley, 2007.