Animal Behavior

"Fido" or "Freddie"? Why Do Some Pet Names Become Popular?

Three tips for picking a popular pet name.

Posted September 18, 2018

“To name a dog is to make him personal…” Alexandra Horowitz

I first became interested in names when I read an article in which researchers Alex Bentley and Matt Hahn showed how changes in popular baby names offer an excellent model for studying cultural evolution. Alex, Matt and I subsequently found that, just like baby names, whether a dog breed becomes popular is mostly a matter of dumb luck. (See What Do Irish Setters and Girls Named "Jennifer" Tell Us About the Causes of Social Change?) Recently, however, I discovered that the most popular names for dogs in the United States tend to have three characteristics in common.

Our Changing Relationships With Pets

The names we give our pets reveal much about changes in how we think about animals. Take Presidential pets. Only three United States presidents have been petless — James Polk, Andrew Johnson, and Donald Trump. Although Lincoln had a pet pig and Teddy Roosevelt a flying squirrel, the most common presidential pets have been dogs. Some the presidents’ pooches had strange names. There was Drunkard (Washington), Satan (John Adams), Him and Her (Lyndon Johnson’s beagles), and, my favorite, Veto (Garfield). Shifts over time in the names of White House dogs reflect our changing attitudes toward companion animals. Thirty percent of the 110 First Dogs had human names, including Mike (Truman), Heidi (Eisenhower), and Barney (George W. Bush). The other 70% had decidedly non-human names like Faithful (Grant) and Fido (Lincoln). While only one of the presidents between Washington and Lincoln had a dog with a human name, all 12 of the dog-owning presidents since FDR did. The fact that post-World War II presidents were more likely to give human names to their dogs is indicative of general trend the pet product industry refers to as the “humanization of pets.”

Researchers who study human-animal relationships have used pet names as a window on our relationships with pets. Ernest Abel of Wayne State University, for example, found that dogs and cats were much more likely to be given human names (48% and 42% respectively) than were pet birds (23%), fish (22%), reptiles (20%) or horses (14%). Pet names also reveal cultural differences in how we think about other species. While pets are commonly given human names in the United States and Poland, this is not true in Taiwan. According to a 2017 study published in the journal Names, Taiwanese pets are rarely given human names. Rather, the most common pet names are combinations of repeated syllables, the Chinese equivalents of Fifi or Kiki. The second most popular pet name category consists of food-based names like Pork Chop, Moon Cake, Chocolate, and Hamburger. Among the third most common category of pet names in Taiwan are terms of endearment such as Great King, Princess, Furry Baby, and Little Fatty.

At the 2018 meeting of the International Society of Anthrozoology, Bradley Smith of Central Queensland University and his student Stephanie Jarvis reported on why dog and cats owners chose a specific name for their pets. One of four respondents said they named a pet based on a reference to a form of popular culture, for example, movies, a sports team or a celebrity. Twenty-one percent of pets were named after non-famous humans, and 20% of dogs and cats were given a name because of their appearance or behavior (for example, Scruffy and Hiccup). And 19% of pet names were references to objects or the pet’s origin. The researchers also reported that cats were more likely than dogs to be named after origins and objects. And, people who scored high on the personality trait of “intellect/imagination” were more likely to name their pets based on references to pop culture or origin/objects rather than give them a human name.

What the 100 Most Popular Dogs Names Have In Common

Intrigued by these studies, I recently spent a rainy afternoon looking for commonalities among the most popular dog names in the United States. I obtained the 100 most frequent dog names for 2015 (50 male and 50 female names) from the website Dogtime.com. (These were based on names of thousands of animals insured by Nationwide Pet Insurance.) I compared these with the Social Security Administration’s list of the 50 most popular male baby names and 50 most popular female baby names in the United States. I found three trends that generally characterized the most popular dog names.

- Humanization. Nowadays, nearly ALL the really popular names for dogs are traditionally human names. Eighty-nine percent of the 100 most common dog names were human names. These included 86% of the most common names for male dogs and 92 % of female dog names.

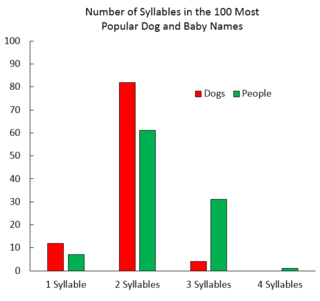

- Length. Dog names tend to be shorter than human names. As shown in this graph, 82% of the

Source: Graph by Hal Herzog

Source: Graph by Hal Herzogpopular dog names have two syllables. Human names were eight times more likely than dog names to be three or four syllables long. In a study of golden retriever names, Ernest Abel and Michael Kruger found that male dogs tended to have shorter names than female dogs. However, this was not true among the 100 most popular dog names. The average name of both males and female dogs was 1.88 syllables.

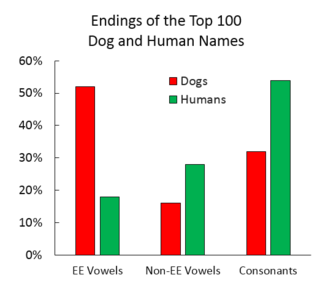

- Endings. The biggest difference between dog and human names was in their endings. Half of dog names ended in the long “ee” vowel sound such as Baily, Lucy, Dixie. This is compared to

Source: Graph by Hal Herzog

Source: Graph by Hal Herzogonly 18% of human names that ended in the long “ee” sound. In contrast, 54% of human names ended in a consonant sound. And, as other studies have reported, the preference for consonants was more evident in human males. Eighty percent of boy babies had a name ending in a consonant, compared to 28% of girl babies and 42% of male dogs.

The Pet Name Popularity Index

According to my analysis, popular dog names tend to be (a) human, (b) contain two syllables, and (c) end in a long “ee” vowel sound. I used these three characteristics to make a scale which, in theory, should predict the chances of a dog name will become popular. I call it the Pet Name Popularity Index (the PNPI).

Here’s how it works. Your pet’s name gets 1 point for each of the three popularity characteristics it possesses. The scores on the scale can range from 0 to 3. For example, pets named Spud or Cullasaja (the name of my son’s cat) would get PNPI scores of 0 as they do not have any of the three characteristics of popular pet names. In contrast, a dog named Charlie or Josie would score 3 on the PNPI.

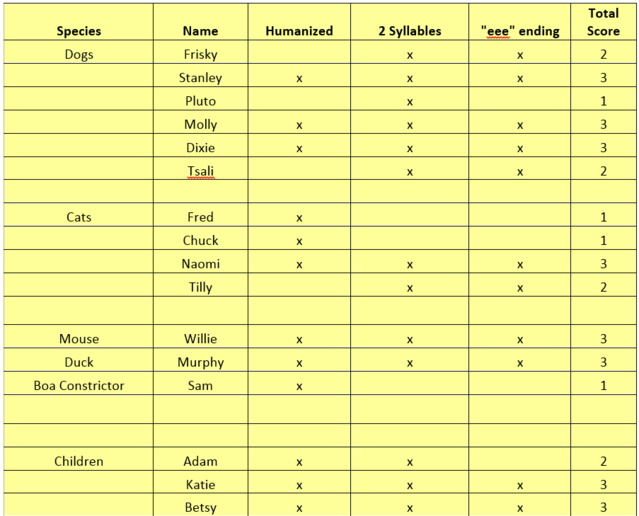

As a trial run, I calculated PNPI scores for the names of the thirteen pets that have been a part of my life over the years: six dogs, four cats, a mouse, a duck and a boa constrictor. The data are shown in the table below. The average PNPI for the dogs was 2.33 while cats came in at 1.75. Willie (our pet mouse) and Murphy (my childhood pet duck) maxed out with scores of 3. Our boa constrictor, Sam, on the other hand, only got a 1; he had a human name, but it had only one syllable and did not end in an “ee” sound.

By comparison, my human children had an average PNPI score of 2.66. That’s because Adam got 2 on the scale. The kids did, however, did beat out our dogs and our cats.

References

Abel, E. L. (2007). Birds are not more human than dogs: Evidence from naming. Names, 55(4), 349-353.

Abel, E. L., & Kruger, M. L. (2007). Gender related naming practices: Similarities and differences between people and their dogs. Sex Roles, 57(1-2), 15-19.

Chen, L. N. (2017). Pet-Naming Practices in Taiwan. Names, 65(3), 167-177.

Herzog, H. A., Bentley, R. A., & Hahn, M. W. (2004). Random drift and large shifts in popularity of dog breeds. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 271(Suppl 5), S353-S356.

Hahn, M. W., & Bentley, R. A. (2003). Drift as a mechanism for cultural change: an example from baby names. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 270(Suppl 1), S120-S123.

Preȩgowski, M. P. (2016). Human names as companion animal names in Poland. In Companion Animals in Everyday Life (pp. 235-250). Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Smith, B. & Jarvis, S. (2018) What's in a (dog) name? Presentation at the meeting of the International Society for Anthrozoology. Sydney, Australia.