Genetics

25 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Dogs

Recent discoveries in the hot new field of canine science.

Posted March 13, 2017

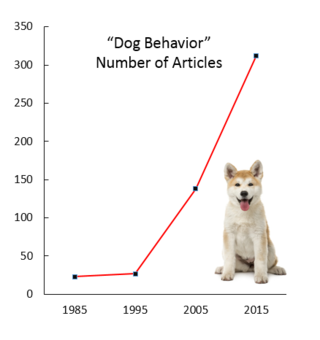

Canine science is hot right now. After decades when behaviorists focused their attention on lab rats and pigeons, the number of scientific publications on dogs published each year has jumped ten-fold*, according to Google Scholar, and new research centers are popping up worldwide.

This explosion of knowledge makes it hard to keep up with the latest discoveries on dog behavior and biology. That makes the new, long-awaited edition of The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior, and Interactions with People an invaluable resource for researchers and enthusiasts. Edited by James Serpell, a pioneer in the field of anthrozoology, The Domestic Dog is a compendium written by a who’s who of canine researchers. I concur with dog guru Marc Bekoff, who wrote in his Psychology Today review that the book was “inarguably, the go-to reference on dogs.”

Here are 25 new things I learned about dogs from the book:

Behavior and Cognition

- Looking for a good family pet? You might want to avoid akitas, shar peis, and chow chows. Veterinarians rated them as the breeds least affectionate to family members. Golden retrievers and labs topped the list of the most affectionate breeds.

- Researchers still do not know for sure if dogs experience emotions such as guilt, empathy, or a sense of fairness.

- Randall Lockwood points out in his chapter that, despite hundreds of studies, researchers still don’t know why herding dogs herd and hunting dogs hunt.

- The sound of a human yawning can make dogs yawn.

- Everyone knows that cats are predators, but more than 60 studies have found that feral dogs can wreak havoc on wildlife. Before it was finally shot, a single dog killed 500 brown kiwis on a New Zealand island – over half the population.

Human-Dog Interactions

- Europe and Japan have well-documented central certification systems for service dogs. The United States, however, has no government-recognized certification system for assistance or emotional support animals. (See this post.)

- In 2012, the U.S. Veterans Administration determined that there was insufficient evidence that dogs actually reduced mental-health problems in veterans.

- Puppies purchased at pet stores are more likely to attack their owners than dogs obtained from non-commercial breeders.

- Dog bites account for more than one-third of insurance liability claims.

- Over 50 percent of dogs in Europe are overweight.

- Despite all the hype about the medical benefits of pet ownership, there is no evidence that petting a dog has any long-term positive effects on human health.

- Each year about 55,000 people are killed by rabies, and 95 percent of these cases are caused by dog bites.

Development and Sensory Capacities

- Wolves and dogs are functionally blind until they are about a month old. Even so, wolf puppies begin to walk and explore when they are about two weeks old, while dog pups don’t exhibit these behaviors until they are four weeks old.

- Even as puppies, breeds show large differences in behavior. For example, beagles and cocker spaniel puppies almost never argue over food, while shelties fight like crazy for five weeks, and then suddenly quit. Basenji litter mates are aggressive and continue to fight with each other for a year.

- Dog fetuses can learn. Pups whose moms ate food laced with anise seeds when they were pregnant were attracted to the smell of anise soon after they were born.

- Dogs should not drive cars: They see red as black.

Biology and Genetics

- Dogs with flat faces are lousy when it comes to giving facial signals, and breeds with long bodies are not very good at transmitting visual signals, such as play bows.

- Genes seem to have less impact on individual differences in canine behavioral traits than they do on human personality traits.

- Short legs on dachshunds, corgis, and basset hounds are caused by the action of a single “retrogene” controlling a growth hormone critical for fetal development.

- Molecular geneticists have made great progress in understanding how genes control the size, shape, and color of dogs. However, researchers still do not know much about the specific mechanisms by which genes affect canine behavior.

Cultural Differences

- The Onges people of the Andaman Islands are devoted to their hunting dogs, even though they (the people) suffer nearly constant flea infestations, are often bitten by their dogs, and are frequently kept awake all night by “continuous barking and howling.” In contrast, the BaMbuti Pygmies treat their hunting dogs with extreme violence and abject cruelty.

- In the Polynesian islands, dogs were on the menu. However, puppies breastfed by lactating women were never eaten.

- In central Italy, free-ranging dogs who live in villages are solitary, like foxes. But dogs that live in the countryside, like wolves, live in groups.

- Free-ranging dogs in Italy have it tough — 95 percent of puppies die before they are a year old.

- Few dogs are spayed and neutered in Scandinavia, yet unplanned litters of puppies are surprisingly rare.

Dogs as Constant Moral Reminders

Finally, as befitting one of the most innovative minds in anthrozoology, the editor of The Domestic Dog, James Serpell, really delivers in his chapter on our conflicted attitudes towards dogs. He points out the moral implications of bringing dogs into our lives as companions and family members and argues that our close relationships with dogs undermine the convenient barrier humans erect between man and beast. Bonding with dogs, he suggests, is the first step along a morally slippery slope, as they are constant reminders that animals are creatures that deserve moral consideration. He writes, “Seen in this light, our ambivalence towards the dog is ultimately an expression of the profound uncertainty we humans feel concerning our assumed ‘right’ to live at the expense of other sentient beings.”

I wish I had said that.

* Thanks to Marc Bekoff for pointing out that the original version of the graph with the number of articles on dog behavior contained a error. This is the corrected version.

Hal Herzog is professor emeritus of psychology at Western Carolina University and author of Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It's So Hard To Think Straight About Animals.

Follow me on Twitter.

References

Serpell, J. (2017) The domestic dog: Its evolution, behavior and interactions with people. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (2nd edition).