Animal Behavior

Do Pets Go To Heaven?

If dogs go to Heaven, what about their fleas?

Posted May 30, 2012

The evangelist Billy Graham is being buried today, and I am wondering if he is sharing Heaven with his dog Lars.

The Reverend Billy Graham was a big presence in western North Carolina. In fact, he lived only about 20 miles from my house. Not surprisingly, my local paper featured his regular advice column My Answer. My favorite letter was from a concerned pet lover named Mrs.Y who wanted to know if she would be reunited with her beloved dog in Heaven.

In his response to Mrs. Y, Dr. Graham explained that only humans have souls. He also acknowledged that this poses a problem for pet owners who cannot imagine they would be happy in Paradise without their pets. However, he resolved this paradox by suggesting that individual pets will be allowed in Heaven if their owner’s happiness depends on the presence of their companion animal.

But if dogs and cats can go to Heaven, why not chimpanzees, horses, birds, or even mosquitoes and worms? Several years ago, prodded by Reverend Graham's column, Western Carolina University students Sean Kearny and Alexandra Foster and I decided to study what people think about whether all dogs—or for that matter, their fleas—go to Heaven.

“Theological Anthrozoology”—The Animals In Heaven Scale

We could not find any find any previous studies on our collective beliefs about the status of other species in the afterlife. So in a first stab at the new field of “theological anthrozoology,” we constructed a scale to assess views about what happens to animals when they die. We were interested two questions.

- Which animals do people think go to Heaven?

- Is there a relationship between anthropomorphism (the tendency to project human characteristics onto non-human objects) and beliefs which species go through the Pearly Gates?

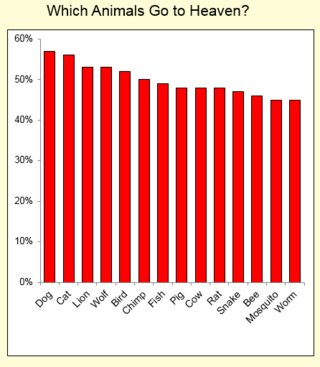

Our “Animals In Heaven Scale” consisted of a list of 14 species—from dogs and chimpanzees to bees and worms. Participants were asked whether thought each species went to Heaven (yes, no, or unsure). Their total AIHS scores were calculated by simply adding up the number of species people think go to Heaven. Our survey also included a general measure of religious attitudes, including the belief in Heaven. Finally, subjects completed a standardized measure of anthropomorphism (here).

We gave our scale to 109 students taking psychology classes at Western Carolina University, an institution whose student body is predominantly rural/suburban, Southern, White, and Protestant. Even though our results cannot be generalized to Americans as a whole, I think Animals and Us readers will find them interesting.

Who Goes Through Heaven’s Gates?

Seventy-five percent of the students believed that people went to Heaven, and most students who believed in Heaven thought that animals went there. But what species are allowed to enter Heaven’s Gate? I anticipated that a lot of the students would say that dogs and cats go to Heaven, but I also figured that only a few of the subjects would accord the same privilege to pigs, snakes, worms, and mosquitoes. I was wrong.

Not surprisingly, at the top of the list of Heaven-bound animals were dogs (57 percent of all subjects thought dogs went to Heaven) and cats (56 percent). However, almost as many as participants felt that Heaven has a place for fish (49 percent), rats (48 percent), snakes (47 percent), mosquitoes (45 percent) and even earthworms (45 percent). Indeed, a large majority of the students who thought that any animal could go to Heaven felt that all species did.

I was surprised by these results, so we started asking people about their views on animals and the afterlife. There were some exceptions to the “all animals” principle. For instance, one person told us “Mosquitoes will burn in Hell!” and another drew the proverbial line between bees and worms because “bees have a sophisticated society.” However, the zoo-theology of most of the students was exemplified by a graduate student who told me that the fleas and ticks on her dog go to Heaven. When I looked doubtful, she earnestly said, “That’s right. If my dog goes to Heaven, all animals do.”

Finally, as we expected, people scoring high on the Animals in Heaven Scale also tended to be highly anthropomorphic.

The Importance of Theological Anthrozoology

I admit that our study has limitations (an unrepresentative sample), and I am not about to submit it for publication in a peer reviewed journal such as Anthrozoos. But one of advantages of writing a blog is that you can toss around interesting issues that might not be suitable for a traditional academic publication.

Some of the issues that the specter of animals in Heaven raise for me are:

1.What do predators eat in Heaven? When I ask people about this, they usually say that in Heaven you don’t need to eat anything. (As a person who finds great enjoyment in the culinary arts, I find this idea alarming.)

2. Will my cat Tilly get to torment chipmunks in Heaven? After all, it’s one of her favorite activities.

3. How do people feel about eating Heaven-bound creatures? Does believing that a cow goes to Heaven make it harder or easier to eat beef?

4. How much are people willing to pay to communicate with their dead pets? Scads of people claim they can put you in touch with your deceased companion animal. (Just Google “pet communicator.”) A self-described “pet psychic’ named Terri Jay, for instance, charges $45 per half hour to “find your old pet in its new reincarnated body.” (Personally, I would not want to find out that Molly, our beloved Lab came back as a factory farmed chicken.)

A Serious Issue

The topic of what people believe about animals and the afterlife is important for theological, ethical, and psychological reasons. I certainly find it comforting to think that Molly—the dog you only get once in a lifetime—has crossed the Rainbow Bridge.