Smoking

Why Are There So Few Vegetarians?

Most "vegetarians" eat meat. Huh?

Posted September 6, 2011 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

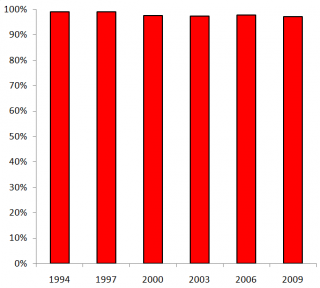

- Between 1994 and 2009, the percentage of meat-eaters in the United States varied between 97% and 99%.

- In one study, 60% of self-described "vegetarians" admitted that they had consumed red meat, poultry, or fish the previous day.

- The anti-meat campaign may have failed due to biology: Humans get a lot of nutrients and calories from meat.

Now that Bill Clinton has become a vegan, he is a member of two very small minority groups — living ex-presidents and people who do not consume any animal products. True, there are more vegans than ex-presidents. But the number of vegans is also quite small — less than 0.8% of the U.S population.

It's not really surprising that so few Americans are vegans who not only give up pork chops and steak, but also ice cream, cheese, honey, and pizza. What is more surprising is the relative rarity of vegetarians — people who simply do not eat any meat. Every three years, the Vegetarian Resource Group commissions a national survey on the diets of Americans. The graph below shows their statistics on the percent of Americans who eat animals at least some of the time. Between 1994 and 2009, the percent of meat-eaters in the United States varied between 97% and 99%. (A research team from Yale University puts the number of "strict" vegetarians at less than 0.1%.) Whatever the exact numbers, it is clear that Americans are not en masse forsaking burgers and barbecue for tofu.

Why Do So Many "Vegetarians" Umm...Lie About Their Diets?

If there are so few true vegetarians, what about all those books that claim we are in the midst of a dietary revolution? Don't believe them. The reason for the widespread but mistaken belief that America is rapidly going veg is the mismatch between what people say they eat and what they actually eat. Take a 2002 Times/CNN poll on the eating habits of 10,000 Americans. Six percent of the individuals surveyed said they considered themselves vegetarian. But when asked by the pollsters what they had eaten in the last 24 hours, 60% of the self-described "vegetarians" admitted that that had consumed red meat, poultry, or fish the previous day. In another survey, the United States Department of Agriculture randomly telephoned 13,313 Americans. Three percent of the respondents answered yes to the question, "Do you consider yourself to be a vegetarian?" A week later the researchers called the participants again and this time asked what they had eaten the day before. The results were even more dramatic than the Times/CNN survey: this time 66% of the "vegetarians" had eaten animal flesh in the last 24 hours.

How can so many people square their identification as a "vegetarian" with the fact that they regularly eat animals? Often, they adopt a morally convenient definition of the term vegetarian. To me, the term vegetarian describes the diet of a person who does not eat animals — period. One of my friends, on the other hand, considers herself a vegetarian because she only eats creatures that "swim or fly." Another vegetarian told me that she does not eat animals that have a face — and she does not think that fish have faces.

The Campaign to Moralize Meat-Eating Has Failed

In 1975, the philosopher Peter Singer published his groundbreaking book Animal Liberation which jump-started the contemporary animal rights movement. Since then, animal protectionists have achieved some impressive successes. The number of dogs and cats killed in animal shelters each year has plummeted by 90%, and states like Florida, Arizona, Oregon, Colorado, and California have enacted legislation to improve the conditions of animals on factory farms. In contrast, the 30-year campaign by animal activists to equate meat with murder has hardly made a dent in our collective desire for flesh.

The great paradox of our culture's schizoid attitudes about animals is that as our concern for their welfare has increased, so has our desire to eat them. In 1975, the average American ate 178 pounds of red meat and poultry; by 2007, the number had jumped to 222 pounds. And while the number of cattle killed for our dining pleasure has decreased by nearly 20% since the publication of Animal Liberation, the number of chickens killed in American slaughter houses has jumped 200%. According to a recent report by the highly credible Humane Research Council, if you include dairy and eggs, an astounding 920 pounds of animal products slides down the average American's throat each year.

"Moralization" is the cultural transformation of a preference into a value. Attitudes toward cigarette smoking is an example. About the same time the animal rights movement was gearing up in the 1970s, the anti-tobacco forces were also getting their act together. Since then, the rate of smoking among American adults has dropped from nearly 50% to less than 25%. In contrast, the number of meat eaters has remained stable, hovering around 98%.

The argument against eating animals is powerful on ethical, environmental, and heath grounds. (See this essay by the philosopher Mylan Engel.) Why has the effort to make smoking a moral issue been so successful while the anti-meat campaign has failed? I blame it largely on biology, though meat industry propaganda also plays a role. Meat, it seems, is more addictive than nicotine. Chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, love meat. In terms of nutrients and calories, you get a lot of bang for the buck in meat, and many paleoanthropologists argue that the explosion in the size of the human brain over the last two million years was fueled by meat. The most "natural" of our relationships with animals may well be our desire to eat them. The problem is that being "natural" is not the same thing as being "morally right."

Vegans as Moral Heroes

In his book, The Happiness Hypothesis, the psychologist Jonathan Haidt discusses his reaction to reading Peter Singer's argument against animals. He writes, "Since that day, I have been morally opposed to all forms of factory farming. Morally opposed but not behaviorally opposed. I love the taste of meat, and the only thing that changed the after reading Singer is that I thought about my hypocrisy each time I ordered a hamburger."

Meat inhabits the psychological territory that Al Pacino's character in The Devil's Advocate refers to as "the no-man's land between mind and body." Most people (including me) are like Haidt when it comes to meat. We succumb to the whisperings of our genes. Maybe that's why I regard ethical vegetarians and especially vegans as moral heroes. Unlike most of us, they take ethical issues seriously. They enter the fray between mind and body...and they win.

Is President Clinton up to the task?

Bill, I'm rooting for you.