Mild Cognitive Impairment

Movies' Superheroes and Religions' Superhumans

Why have superhero franchises captured the movie business?

Posted November 10, 2019

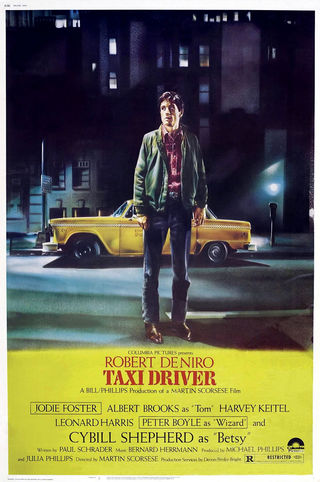

Responding to widespread criticism of his comments about superhero movies in an interview in October, Martin Scorsese, the famed film director, distinguishes between what he calls “cinema” and “franchise pictures” in a recent column. Scorsese, the director of such well-known movies as “Taxi Driver,” “Goodfellas,” and “The Wolf of Wall Street,” reveres cinema, which involves complex, even paradoxical characters and is about “aesthetic, emotional and spiritual revelation.” Cinema, in short, is movie-making as an art form. Franchise pictures, by contrast, are “market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted, and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.” They lack mystery. They take no risks. They foster what Ross Douthat describes as a “state of arrested development” in their audiences.

Scorsese’s description of these franchise pictures as “worldwide audiovisual entertainment” reflects his understanding that such superhero franchise pictures are money-makers for the corporations that produce them and have played a role in sustaining movie theaters all over America and the world in the face of myriad digital entertainment delivery systems that compete with cineplexes.

Finally, though, Scorsese’s primary concern is that the popularity of these superhero franchise pictures has substantially reduced opportunities for seeing cinematic films on the big screen. As Mark Harris has noted, these franchise pictures “are not the biggest part of the movie business. They are the movie business.” They completely dominate the motion picture industry.

Scorsese’s Explanation

Scorsese rejects the claim that these franchise pictures thrive as the result of straightforward supply and demand. He does not think that this development can be explained in terms of movie-makers just giving customers what they want. Scorsese maintains, instead, that “if people are given only one kind of thing... of course, they’re going to want more of that one kind of thing.” Scorsese seems to think that once something has become familiar, people will want nothing else.

That claim is not obvious. Its plausibility depends upon something like the earlier claim about the aesthetic impact of such superhero franchise pictures. It is, presumably, precisely because these movies arrest their viewers’ aesthetic development that they fail to be attracted to, let alone, demand something better.

What Superhero Movies and Religions Have in Common

Whether arrested aesthetic development leading to uncritical-satisfaction-with-the-familiar is on the mark or not, the cognitive science of religions offers additional explanatory resources for making sense of the popularity of superhero franchise movies. In short, Hollywood has found its way to a prominent cultural attractor, toward which religions have gravitated for millennia, viz., offering up representations of agents who possess counter-intuitive properties.

By now, nearly two decades of experimental research in the cognitive science of religions have demonstrated the transmission advantages such representations enjoy. Whether with movie superheroes or religions’ superhuman agents, they usually exhibit, in any given episode, only one counter-intuitive property at a time, resulting in minimally counter-intuitive (MCI) representations. MCI representations approximate a cognitive optimum. They most effectively balance the trade-offs between:

- those representations’ capacity to grab people’s attention,

- their memorability, and

- the number of default inferences that people can draw instantly from them. (People draw such inferences primarily on the basis of their implicit knowledge about the underlying ontological categories the representations involve.)

Multiple experimental studies, including cross-cultural experimental studies, have provided ample evidence for MCI representations’ mnemonic advantages compared with both mere oddities that are not counter-intuitive (e.g., a chocolate table) and representations involving many counter-intuitive properties (e.g., a tree that hears people’s conversations, moves about the territory at night, and becomes invisible on the Sabbath day).

The theory of MCI representations in the cognitive science of religions also accounts for another feature of superhero movies. It explains their world-wide appeal. That is because it looks to, what the theory maintains are, elemental features of human minds, on which diverse cultural arrangements have little influence.

References

Banerjee, Konika, Haque, Omar, & Spelke, Elizabeth (2013). Melting lizards and crying mailboxes: Children’s preferential recall of minimally counterintuitive concepts. Cognitive Science, 37(7), pp. 1251-1289.

Boyer, Pascal (2001). Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. New York: Basic Books.

Boyer, Pascal, & Ramble, Charles (2001). Cognitive templates for religious concepts: Cross-cultural evidence for recall of counter-intuitive representations. Cognitive Science, 25(4), 535-564.

Sperber, Dan. (1996). Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.