Autism

Words are not Things

Why labels work better on Pop Tarts than people.

Posted September 29, 2014

Robert Graves--author, classicist, WWI soldier, and extremely intelligent guy--wrote this poem in 1927:

Children are dumb to say how hot the day is,

How hot the scent is of the summer rose,

How dreadful the black wastes of evening sky,

How dreadful the tall soldiers drumming by,

But we have speech, to chill the angry day,

And speech, to dull the roses's cruel scent,

We spell away the overhanging night,

We spell away the soldiers and the fright.

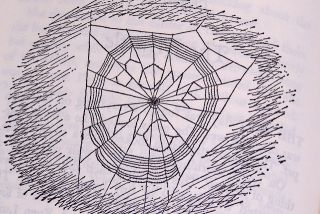

There's a cool web of language winds us in,

Retreat from too much joy or too much fear:We grow sea-green at last and coldly die

In brininess and volubility.

But if we let our tongues lose self-possession,

Throwing off language and its watery clasp

Before our death, instead of when death comes,

Facing the wide glare of the children's day,

Facing the rose, the dark sky and the drums,

We shall go mad, no doubt, and die that way.

_________________________________________________

There is a method to my madness, Readers. This poem is important. Stay with me, even though I’m going to start with the Pop Tarts, to get them out of the way.

(Apologies to the ghost of good Mr. Graves. Although the “toaster pastries” in question can be tasty, connecting them rhetorically with your poem is admittedly something of an insult. Even the brown sugar ones, which make me regret ditching wheat and processed foods when I think too hard about them.)

Processed food labeling, so long as it is practiced honestly and with reference to The Rules, is a good thing--if for no other reason than that we can make educated (OK, quasi-educated?) decisions about what we eat.

We all have our criteria. Here is my number one: if the first ingredient is one I cannot pronounce, or of indeterminate animal-vegetable-mineral status, I try to say no. Fortunately, I am given that choice.

The second reason I approve of food labeling is that no Pop Tart or Toaster Strudel or Kap’n Krunch, or what-ever-you-may, has EVER had its feelings hurt or its life-prospects diminished, by a disingenuous or ill-informed or cruel label. Transparency in labeling may take some of the worst offenders off the shelves, but since these foods were, for the most part, never technically alive, no life-prospects were harmed in said labeling.

As a matter of fact, quite the opposite.

Now, back to more important matters, like poetry. And people.

I first encountered “The Cool Web” (see above) in 1983, give or take a year or two. And I loved it. (Forget about the fact that words and webs spun together invoke my very favorite childhood chapter book--and maybe yours--Charlotte’s Web. I only just noticed that coincidence as I'm writing this.)

Robert Graves understood something important about words, titles, sentences, labels. What he knew was that WORDS DO NOT EQUAL THINGS. As soon as we label an experience, a vision, a sensation, a thought--we lose it. The word(s) step in, they replace, and in some ways they diminish, this “thing” we wish to make sense of.

“We spell away the overhanging night,

We spell away the soldiers and the fright.”

Words can blunt the sharp edges of things. Horrors like trench warfare, and rats, and grenades, and bayonets, and mustard gas, and the cold, wet mud that gives you trench foot-- if the rats haven’t already eaten your feet clean off.

OK, I made that last thing up. On the other hand, I’ve not Googled it, so who knows? It could be true.

Words give the things we encounter in this world meaning and context. And they can be used to explain away horrors, to help us feel that we have power over our lives.

That’s a useful thing--sometimes. Remember the story of the Biblical Adam naming all the things in his brand-new world?

And how eventually Darwin and other scientists classified all parts of nature with labels? “King Phillip Came Over From Germany, Swiftly” are the words that helped me remember the REAL words that order our biological world: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species.

Scientists did this labeling (and still do), in part because naming things allows us to think deeply about them. To figure out their relationship to us. And in some ways, to conquer them.

If we feel we can *know* the stuff that is not us, then we feel a little safer. Using language to order that outside stuff essentially de-fangs it. Which is exactly why we need the cool web of language. Otherwise, says Graves, we would just go mad and die.

But words can obfuscate as well as illuminate. They can mislead. And they can hurt--even as much, sometimes, as the physical hurt that comes of bayonets and rat bites and cold, wet mud.

OK. And your point? (I know exactly what you’re thinking, Readers.)

Well, here’s my point. (We took the scenic route, but hey--we got here.) I wrote a post recently, the one before this one, that provoked a few painful, cruel, and ill-informed responses. I deleted them. And I will delete any other responses that engage in hateful or hurtful discourse. By all means, disagree with me! Start a debate! But do remember that every reader and writer on this forum is a human being, and deserving of respect.

I think there were two reasons for these strong reactions. Maybe three.

- The title of the piece was inflammatory (I did that on purpose. It might not have been a great idea.)

- I was alluding to recent events here in America that arouse very strong emotions in people.

- I used labels (i.e. “mentally ill” and “Autism/Asperger’s Syndrome”) as if they are directly anchored to some truth, some unambiguous thing.

We are not Pop Tarts, Readers. And we cannot be reckoned like a grocery bill, even if you think you know our labels and our worth.

I take responsibility for creating the conditions that nourish misconception about some very complex conditions. I should have known better than to throw labels about with such careless abandon.

WORDS DO NOT EQUAL THINGS, Dr. Vlock. (Yes, I am talking to myself. I have a bad habit of doing that, especially when I think no one is listening.)

I have struggled with using the phrase “mental illness” in my writing for as long as I’ve been publishing about disorders of the psyche. It is not a good term. It conveys only the most general kind of meaning. And it does not do justice to the fact that mental health disorders come in practically limitless shapes, depths, and colors.

As is the case with autism disorders, psychiatric illnesses fall along a wide spectrum. As my autism-parent friends like to say, “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism." Badabing!

I mentioned my son and Adam Lanza together in that partly-regrettable post, as if they belong together because of “Asperger’s” and “mental illness.”. I wish I hadn’t. Whatever ailments the latter suffered from, there was not ONE IOTA of him that resembled my son. It may be that they share(d) a couple of labels. But, you know. Words are not things.

So, Readers? I owe you an apology. Not because I suggested we all bear a certain responsibility for those moments when utter madness erupts in our communities. But because I made assumptions about what experiences you would bring to my last post that made neither clinical nor ethical sense. And the result was a real bummer, to put it mildly.

Unfortunately, we writers need to consider issues of style as well as meaning. It sounds better when you simply write “mentally ill,” instead of making your readers slog through “suffering from unipolar depression, agoraphobia with panic disorder, and OCD” (for example).

I bring to each and every piece I write one standard assumption that I DO think works: if we are bipedal with opposable thumbs, and we are not apes. then we are human. Sometimes humans do unbearably horrible things. Not every one of those who does “is mentally ill,” or “has Asperger’s Syndrome.” Humans in general deserve to be treated with empathy and respect--unless we have hard evidence that they deserve otherwise.

We do indeed exist in the middle of a vast, cool web. A network of words. These words make us feel power over other people, and over challenging events. But in many ways they separate us from each other, and from some things that are beautiful and intense in this world.

Oh, and by the way: the majority of people with mental health challenges just aren’t dangerous, even though they appear to be when we consult the media, popular entertainment, or public opinion.

Think I’m off my rocker? Read this:

In reviewing the research on violence and mental illness, the Institute of Medicine concluded, “Although studies suggest a link between mental illnesses and violence, the contribution of people with mental illnesses to overall rates of violence is small,” and further, “the magnitude of the relationship is greatly exaggerated in the minds of the general population” (Institute of Medicine, 2006). For people with mental illnesses, violent behavior appears to be more common when there’s also the presence of other risk factors. These include substance abuse or dependence; a history of violence, juvenile detention, or physical abuse; and recent stressors such as being a crime victim, getting divorced, or losing a job (Elbogen and Johnson, 2009).

You can find the whole thing here.

Last but not least, thank you, Readers, for being out there!