BDSM

Personality Traits of BDSM Practitioners: Another Look

A recent study provides another glimpse into the world of BDSM.

Posted February 14, 2015 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Recently, the practice BDSM (bondage and discipline, dominance/submission, sadism-masochism) has generated a great deal of interest among lay-people and academics alike. The best-selling novel Fifty Shades of Grey and the new film of the same name have helped bring an otherwise stigmatised phenomenon into mainstream awareness. However, this book is apparently not a particularly accurate portrayal of how BDSM is practiced in real life (for example, see this post by sex researcher Justin Lehmiller). Fortunately, this increased interest in the subject has also been accompanied by some new scientific studies that may help to provide more accurate insight into these practices. In a previous post, I discussed a 2013 study that suggests that BDSM practitioners are generally psychologically healthy and that they tend to prefer roles that fit their personalities. In this post, I discuss a newer study that also examined the personality traits of BDSM practitioners using a somewhat different personality model. Some of the findings were highly similar, although there were some differences as well that may be worth exploring further to shed more light on the psychology of BDSM.

BDSM encompasses a diverse range of activities that include but not are limited to the exercise of power and control by one person over another, physical and psychological restraint, and infliction of pain and humiliation. These activities may or may not occur in a sexual context. Typically, someone in a dominant role, known by a variety of terms, including ‘top’, ‘dom or dominant’ or ‘sadist’, will direct the actions of someone in a submissive obedient role, known by such terms as ‘bottom’, ‘sub or submissive’ or ‘masochist’. All activities are consensual and practitioners will negotiate beforehand what they consider acceptable. Many participants have a preferred role they assume in most or all activities, while some prefer to switch roles as desired. Participation in BDSM can range from occasional casual role-playing to a preferred orientation and even to a whole lifestyle with 24/7 role enactments (Hébert & Weaver, 2014).

As discussed in my previous post, there has been some quite interesting research looking into the psychological characteristics of BDSM practitioners. Contrary to what has often been assumed, there is no evidence that BDSM practitioners in general suffer from any particular form of psychological disturbance and in fact they seem to be mentally and emotionally well-adjusted (Richters, De Visser, Rissel, Grulich, & Smith, 2008; Wismeijer & van Assen, 2013). I was particularly interested in the findings of a study of Dutch BDSM practitioners (Wismeijer & van Assen, 2013) which included an assessment of their personality traits according to the Big Five model. The five factors in this model are neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. These are broad personality characteristics that subsume a larger number of narrower more specific traits. According to this study, practitioners in general, including both dominants and submissives, tended to be higher in openness to experience and conscientiousness compared to a comparison sample from the general population. Additionally, participants who preferred the dominant role tended to be lower in agreeableness and neuroticism compared to submissive participants and to the general population, while, submissives tended to be more extraverted than the general population. Additionally, dominants tended to have higher subjective well-being and were less sensitive to rejection compared to the general population, suggesting that people drawn to the dominant role may be particularly psychologically well adjusted.

A more recent study (Hébert & Weaver, 2014) has also examined the personality traits of BDSM practitioners, but this time using the six-factor HEXACO model rather than the Big Five. The HEXACO model has emerged in recent years as a theoretical rival of the Big Five. The most salient difference between the two models is the addition of a sixth factor called Honesty-Humility which subsumes some characteristics (e.g. straightforwardness and modesty) that have sometimes been associated with agreeableness. There are also some other subtle differences, e.g. the equivalent of neuroticism is known by the more neutral name of emotionality. In the Big Five, neuroticism includes a trait known as angry hostility, but in the HEXACO this is associated with low agreeableness. As well as assessing the HEXACO traits, participants in Hébert and Weaver’s study were assessed on self-esteem, satisfaction with life, altruism, empathy, and desire for control. Self-esteem and satisfaction with life are closely associated with subjective well-being. I was therefore interested to compare the findings from this study with the Dutch one, which also assessed subjective well-being.

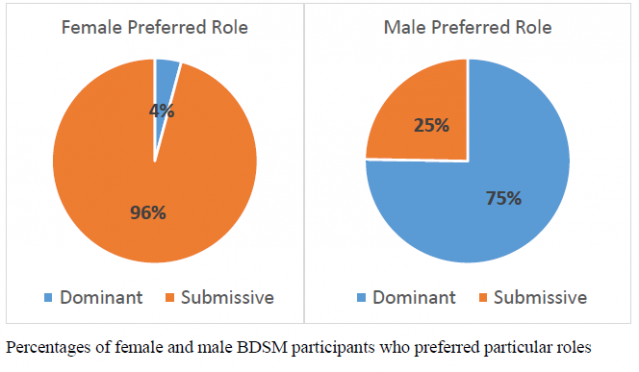

The study by Hébert and Weaver recruited a sample of 270 DSM practitioners through the website Reddit and particularly focused on comparing those who identified primarily as either dominant or submissive. Those who liked to switch between roles were not considered to simplify the comparisons. Much like the Dutch study, there were striking gender differences in preferred role orientations, although these were more marked in this case. As can be seen in the graph I have created below, the vast majority of females in the study preferred the submissive role, suggesting that female dominants may be rather uncommon (and presumably in high demand). The majority of males, on the other hand, preferred the dominant role, although quite a substantial proportion was submissive.

Regarding personality traits, dominants compared to submissives were lower in emotionality, higher in extraversion, and equal in agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness to experience, and honesty-humility. Additionally, dominants had higher self-esteem, satisfaction with a life, and a greater desire for control, but did not differ from submissives in empathy or altruism. The authors compared the participants’ scores to normative data and found that they were within the ‘normal range’ on honesty-humility, emotionality, extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. However, submissives but not dominants scored higher than the normative data on openness to experience. The ‘normative data’ in this case are based on Canadian university students from a previous unrelated study (Lee & Ashton, 2004). This is not an ideal comparison sample but will have to do for the time being. I did my own statistical comparisons with the normative data and found that both dominants and submissives had significantly higher scores in openness to experience compared to the normative data and submissives were significantly higher in conscientiousness.[1]

Some of these results are similar to those of the Dutch study, although there are a few differences. For example, Wismeijer and van Assen (2013) found that BDSM practitioners were high in openness to experience and in conscientiousness compared to the general population which is similar to what was found here. As I noted in my previous article, high openness to experience is associated with willingness to experiment with unusual and unconventional behaviours and in particular with a desire to be sexually uninhibited and to explore novel sexual experiences (Gaither & Sellbom, 2003). Conscientiousness is associated with self-discipline and a liking for orderliness, and rule-following. These characteristics seem well-suited to people who are into something like BDSM. In the Dutch study the statistically largest difference between dominants and submissives was in neuroticism, while in Hébert and Weaver’s study, the statistically largest difference between them was in emotionality, which is highly similar to neuroticism. According to Hébert and Weaver dominants consider it important to remain calm and keep a level head during scenes. People low in neuroticism/emotionality tend to be naturally calm and not easily upset, so this would be helpful in the dominant role.

However, the differences between the Dutch study and Hébert and Weaver also need to be addressed. Extraversion is associated with social assertiveness and willingness to take charge in social situations so it makes sense that dominants might be higher in these characteristics than submissives. However, Wismeijer and van Assen (2013) actually found that submissives had the highest extraversion scores in their sample. Additionally, I have previously argued that it would make sense for dominants to be lower in agreeableness than submissives, which was what Wismeijer and van Assen found, because people low in agreeableness tend to be tough and domineering, and that this would naturally suit them to taking charge during a BDSM scene. However, Hébert and Weaver found no difference at all in agreeableness in their study. The reasons for these differences are not known. However, there are subtle differences in the measures used to assess extraversion and agreeableness in the two studies, and it is possible that these might be reflected in the results.

The Dutch study by Wismeijer and van Assen (2013) used a measure of the Big Five called the NEO-FFI, while Hébert and Weaver used a measure called the HEXACO-60. Close examination of the items used to measure extraversion and agreeableness respectively in each of these instruments reveals some noticeable differences in the way these traits are conceived. Items assessing extraversion in the NEO measure mainly focus on sociability and positive emotions, only one item mentions social assertiveness and none concern social self-esteem. The HEXACO-60 extraversion scale on the other hand has three items relating to social assertiveness and three items assessing social self-esteem. In regards to agreeableness, the NEO agreeableness scale contains items related to tough-mindedness (e.g. “I’m hard-headed and tough-minded in my attitudes”), willingness to manipulate others, and self-aggrandisement. The HEXACO-60 agreeableness scale on the other hand, seems to place more emphasis on forgiveness versus anger, and on general kindness. Although there are important similarities between the scales, they seem to subtly emphasise somewhat different qualities that make up extraversion and agreeableness respectively.

Regarding extraversion firstly, perhaps dominants differ from submissives in regards to being more willing to take charge in social situations and having a more favourable opinion of themselves rather than in regards to being more sociable as such. Note that Wismeijer and van Assen (2013) also found that dominants were less sensitive to rejection, had a lower need for approval than submissives, and that male dominants were more socially confident than submissives. This seems to fit with the notion that dominants are more sure of themselves in their relations with other people. Also relevant is that Hébert and Weaver found that dominants had higher self-esteem and satisfaction with their lives compared to submissives. Self-esteem and satisfaction with life both had large positive correlations with extraversion and with each other in this study. Interestingly, Hébert and Weaver performed an analysis statistically controlling for differences in extraversion and found that dominants and submissives no longer differed in either self-esteem or satisfaction with life. This suggests that these apparent differences were due to the higher extraversion among dominants.

Regarding agreeableness, perhaps the fact that the Dutch study found that dominants were more disagreeable while Hébert and Weaver’s study did not, because dominants may differ from submissives in regard to having a more tough-minded attitude and their willingness to engage in psychological manipulation. On the other hand, dominants might not differ particularly from submissives in regards to anger or willingness to forgive. Furthermore, Hébert and Weaver point out that negotiation of a BDSM scene requires open communication and therefore both parties need to be able to cooperate effectively to create a mutually satisfying outcome and cooperativeness is an agreeable trait. Of course, these conjectures on my part are quite speculative, and it is also possible that dominants and submissives really do not differ that much at all in regards to these traits. More nuanced research using measures of more specific traits such as assertiveness, anger, tough-mindedness, and so on would be needed to determine if these subtle differences are actually present.

Hébert and Weaver’s study also examined a number of traits that have not been investigated before, namely honesty-humility, desire for control, empathy and altruism. They expected that dominants and submissives would differ in all of these respects, but the only significant difference was that dominants expressed a greater desire for control. Hébert and Weaver (2014) mention that they had conducted a small qualitative study (not yet published at the time of writing) and learned that dominants "expressed great pleasure in being able to control the situation and reported this as one of the main benefits of BDSM." They note that dominants fell within the ‘normal range’ of desire for control, hence they suggested that BDSM scenes provide an outlet for a person’s typical desire for control, rather than an expression of an abnormal need to keep control. Hébert and Weaver also considered that submissive abasement in scenes might be an expression of a sense of humility, something which I also speculated about in my previous post. However, this does not appear to be the case. Similarly, the authors thought that submissives might be higher on empathy and altruism, because in their qualitative study submissives described themselves as people-pleasers. However, this was also not the case. On the other hand, this suggests that those in the dominant role are not lacking in empathy either. In fact having empathy might help them to understand and meet the needs of submissives during scenes.

Hébert and Weaver’s study helps contribute to understanding the psychological profiles of those who participate in BDSM. Those drawn to the dominant role appear to be self-confident, assertive, and comfortable taking control. Those who are drawn to the submissive role appear to be more introverted and emotional and enjoy surrendering control. Dominants seem to have a better opinion of themselves and to be more satisfied with their lives compared to submissives, which might be accounted for due to greater extraversion. People of both orientations are open to new experiences and are probably self-disciplined and appreciate structure and rules. Hence, it would seem that people drawn to BDSM choose roles that fit their personalities to a certain extent, although questions remain, such as about the role of more specific traits that are subsumed by the broad factors in the Big Five and HEXACO models. Considering the diverse range of practices involved in BDSM, future research might compare and contrast practitioners with diverging interests in order to foster a deeper of this fascinating area of human life.

Please consider following me on Facebook, Google Plus, or Twitter.

© Scott McGreal. Please do not reproduce without permission. Brief excerpts may be quoted as long as a link to the original article is provided.

Footnote

[1] For the statistically minded, I performed one-sample t-tests using an online calculator using the normative data as reference norms. The results for openness to experience were highly significant for both subs and doms, as were those for conscientiousness in subs (p < .001 in all tests). The result for conscientiousness in doms was not significant (p = .10) even though doms had the same mean score as subs. The dom sample size was smaller than the sub sample size, so the non-significant result may be due to low statistical power.

Image Credits

BDSM collar and chain - Wikimedia Commons

BDSM Dungeon Equipment - Wikimedia Commons

Bondage Art - Wikimedia Commons

Images are reproduced here under Creative Commons Licence agreements and do not imply any endorsement by the image creators.

Other posts about sex and psychology

Porn Stars and Evolutionary Psychology

References

Gaither, G. A., & Sellbom, M. (2003). The Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale: Reliablity and Validity Within a Heterosexual College Student Sample. Journal of Personality Assessment, 81(2), 157-167. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8102_07

Hébert, A., & Weaver, A. (2014). An examination of personality characteristics associated with BDSM orientations. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 23(2), 106-115.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(2 SPEC. ISS.), 329-358.

Richters, J., De Visser, R. O., Rissel, C. E., Grulich, A. E., & Smith, A. M. A. (2008). Demographic and Psychosocial Features of Participants in Bondage and Discipline, “Sadomasochism” or Dominance and Submission (BDSM): Data from a National Survey. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(7), 1660-1668. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00795.x

Wismeijer, A. A. J., & van Assen, M. A. L. M. (2013). Psychological Characteristics of BDSM Practitioners. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(8), 1943-1952. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12192