Trauma

Recognizing and Healing Inherited Trauma

Part 2: A conversation with Jungian therapist and rabbi Tirzah Firestone.

Posted February 28, 2022 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

One fine spring day when I was five, I decided to jump on the back of a neighbor’s schnauzer and ride him around the yard like a horse. Mikey had other ideas. He lept up and tried to chomp on my cheek. Back then, no one called my run-in with Mikey a trauma. The word “trauma” had not yet entered the popular vernacular. But my experience with Mikey was a trauma, and, for many years, I was terrified of dogs.

Times have changed. Discussions about trauma appear everywhere. Simply defined, trauma refers to any deeply disturbing event; in reality, trauma has many nuanced manifestations. Native American scholar and psychotherapist Eduardo Duran calls trauma “the injury where blood does not flow.”

Reference to trauma is now so ubiquitous, it has become almost meaningless. A recent newspaper article suggested that TV audiences are tired of watching gritty, realistic shows about afflictions; they now prefer plots with indomitably cheerful characters like Ted Lasso. It’s understandable we seek entertainment that makes us feel good, but are we denying, ignoring, or dismissing trauma’s impact on our lives and the world? Have we seen, heard, read, and experienced more trauma than we can process? Do we have trauma fatigue?

The truth is there is still much to learn about traumatic experiences. With deeper knowledge, more healing can occur.

Rabbi Dr. Tirzah Firestone has been investigating this terrain for most of her adult life. Her teachings offer new insights, offer synergistic modalities of healing, and instill a sense of agency and hope to the burdened. In her second interview with me for Psychology Today, she offers more insights on the heritability of trauma and how we may be carrying emotional afflictions that do not belong to us.

Dale Kushner: In a recent article for the International Journal of Communal and Transgenerational Trauma, you state that trauma can be transmitted by parents and other adults to the younger generation. This is a startling revelation. Can you explain how you became aware of this fact in your own life?

Rabbi Tirzah Firestone: It’s only in the past several years that evidence of the transference of trauma has been studied in depth. In my own life, the residues of war were deeply imprinted in my parents—my mother escaped Nazi Germany narrowly in 1939, and my father was stationed in the death camps as a U.S. soldier—but they kept their horrors a secret. It was only when I began to seriously study trauma science at midlife that I was able to identify their behaviors as the sequelae of trauma.

DK: Can actual memories be transferred?

TF: It’s well known that children’s psychic borders are highly permeable. Like mirror neurons in the brain,1 the feelings that echo between people, mental images can also be transferred by parents and other adults to the younger generation. Although actual memories aren’t transferred, it’s not uncommon for parents and caregivers who have experienced extreme psychic trauma to transmit to a child what has been called an image deposit2—that is, a mental picture of the excruciating events that they and others from their group have endured.

So, yes, mental pictures—like the Twin Towers in flames on 9-11—with the strong feelings that they evoke, can be passed from generation to generation. They become part of the internal reality of descendants. Seeing one’s home demolished before one’s eyes or one’s town burned to the ground is an experience that rarely dissipates. In my case, the legacy of my father’s trauma from war—the images he saw, the terror he felt, and the rage that ensued over the dehumanization of his people—became part of my visceral inheritance.

DK: How exactly might an adult or caregiver transmit an image deposit?

TF: Numerous studies show that children absorb the stress responses of parents and other caregivers in the wake of traumatic events and invest them with their own meaning.3 For instance, after the events of September 11, 2001, studies on children whose parents and caregivers responded with heightened emotion suffered far more posttraumatic stress than those whose caregivers remained calm or detached.4

Vamik Volkan, who is a student of Erik Erikson and scholar on the topic of collective trauma, calls the powerful mental representations of large-scale trauma internalized images. We’ve already mentioned how permeable the psychological border between the child and caretakers is. Volkan maintains that traumatized adults can unconsciously deposit their internalized images into the developing self of the child. The child then becomes a reservoir for the adult’s trauma images.5

DK: How can a person know if the anxiety, depression, or other mental states of suffering are the result of traumas in the ancestral line or have emerged from their own life experience in the present? Are the two intertwined?

TF: That’s an important question. We hardly need studies to tell us that our family’s trauma affects us. With so much research coming out on intergenerational patterning, it can be a relief to know that we didn’t make up our mental and emotional disposition, but that there may be an ancestral precursor for our anxiety, depression, and even feelings of guilt, shame, or alienation. If we are in doubt, we can do some genealogical work on our families and look at the historical traumas they lived through. Did they endure poverty, displacement, or war? Or maybe their lives were continuously hampered by racial discrimination. These and other residues of extreme life conditions can travel down to us, especially when they are not metabolized.

DK: One trauma researcher has noted that a generation can inherit the “unfinished psychological tasks” of a previous generation. What are some examples of these tasks? What is your role as a therapist in helping a client unburden herself from the unfinished task?

TF: I see intergenerational or ancestral transmissions like suitcases stuffed with important family heirlooms. No matter how weird or troubled you think your family is, there are ancestral treasures in your suitcase, like good values, resilience, or gems of hard-earned wisdom. When I taught at San Quentin, the men shared with me the beautiful legacies they carry and think about daily, mostly from their moms and grandmothers. And then there can be trauma images that we inherit, too.

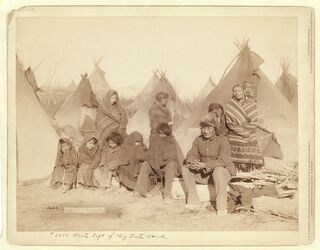

Think about the Vietnam or Syrian wars, or the incursion of Russia into Ukraine. When a large group has experienced massive trauma and severe losses at the hands of enemies, the children of the next generation receive the emotion-charged images of war. Volkan, who studied post-war populations around the world, maintains that embedded in these memories is a task. The next generations receive a “to-do list" associated with the transmitted image.

Unmetabolized tasks translate to the next generations as many things. They might require completing the mourning process over losses, converting shame and humiliation into pride or helplessness into assertion. All these tasks are connected to the mental pictures that are the residue of traumatic events. The image binds the members of the group together in an invisible way.6

DK: Unless younger people are helped to address the unfinished tasks and their psychological legacy, is it true/is there evidence that the psychological reverberations travel horizontally through families and nations, and vertically through time and generations?

TF: Ultimately, it’s up to us, members of the younger generation, to decipher our own psychological landscape. We have to discern what inherited legacies we want to bring forward with us, and what we need to work on and discard. Often we find ourselves doing the hard psychological and emotional work that was left unfinished by our parents and grandparents. Will we continue to internalize our people’s defining historical traumas or reject them? These are the questions every psychologically mature person must ask themselves.

1. van der Kolk, 2014, pp. 58–59, 111–112.

2. Volkan, 2006, 2013.

3. Allen & Rosse, 1998; Scharf, 2007.

4. Shechter & Coates, 2006.

5. Volkan, 2006, 2013.

6. Volkan, 2006, p. 154.

References

Firestone, T. “Transgenerational Trauma Shaping History: The Power of Images.” International Journal of Communal and Transgenerational Trauma, Issue 1, Professional and Philosophical Perspectives, February 1, 2022.

van der Kolk, B. The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain, and Body in the Transformation of Trauma (Penguin: New York, 2014).

Volkan, V. D. Killing in the Name of Identity: A Study of Bloody Conflicts by (Pitchstone Publishing: Durham, NC, 2006, 2013).

Allen, R. D, Rosse, W. Children’s Response to Exposure to Traumatic Events, in Children, Youth and Environments, Vol. 14, No. 1, Collected Papers (2004) Published by University of Cincinnati.

Scharf, M. Long-term effects of trauma: Psychosocial functioning of the second and third generation of Holocaust survivors, Journal of Development and Psychopathology, Vol. 19, Issue 2, April 25, 2007. Published online by Cambridge University Press.

Schechter, D. S., Coates, S. W. Caregiver traumatization adversely impacts young children’s mental representations on the Macarthur Story Stem Battery. Journal of Attachment and Human Development, Vol. 9, Issue 3, December 4, 2007. Published by Taylor & Francis.