Trauma

Trauma: Who is Telling Your Story?

Do you have an unreliable narrator inside you?

Posted April 29, 2019

Have you ever been at a family gathering and someone shares a memory and, as you hear it told, you say to yourself: That’s not the way it happened! The truth is that our memory is an unreliable narrator, a literary term that describes a person telling a story who is not telling it straight. In fiction, an unreliable narrator can be a clever deceiver, as in many crime novels, an innocent lacking self-awareness, or a charming raconteur simply happy to spin entertaining tales.

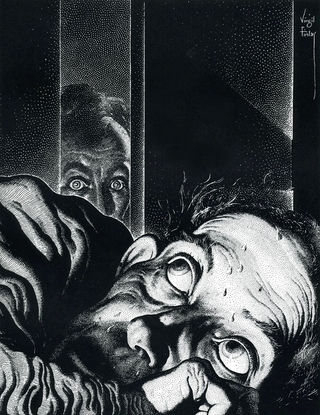

The unnamed narrator in Edgar Allan Poe’s fabulously gruesome horror story, “The Tell-Tale Heart,” is mentally unstable and can’t be relied upon to give accurate information. Wuthering Heights has dual narrators, both of whom have biases about Heathcliff and company. Some unreliable narrators seem to have all their marbles, like Humbert Humbert in Nabokov’s Lolita, but when he kidnaps the precocious Lolita, we conclude he is what he says, a psychopath. In reading a book, there’s a real delight in figuring out who’s lying, who’s manipulating, who’s speaking the truth—but what happens when our own psyches present us with multiple narrators, each with a different set of perceptions and interpretations of reality?

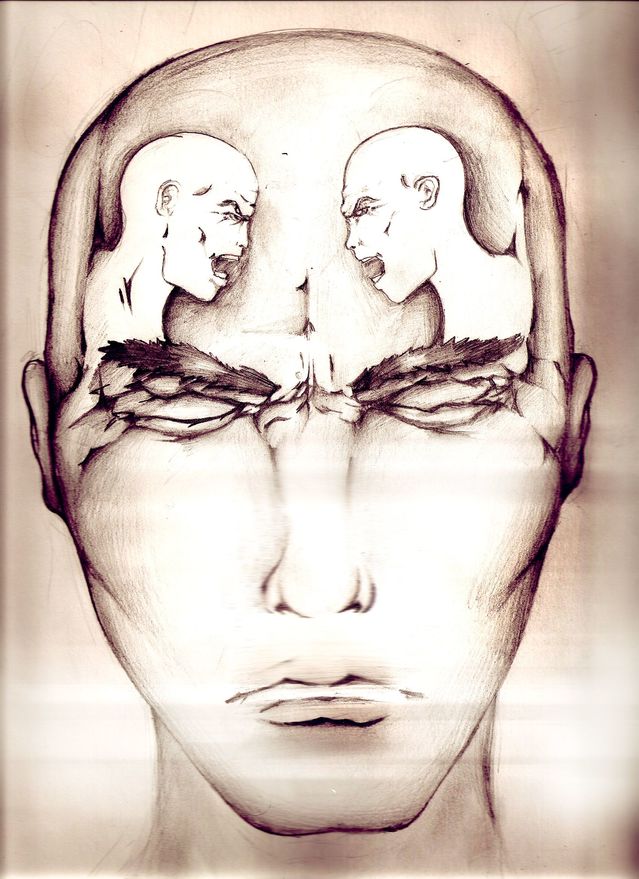

How we see and react to the world is prompted by different parts of the brain. Sometimes, we act on “a gut feeling,” sometimes, we critically think through pros and cons. Both aspects of consciousness, and the spectrum of subtle and complex hues in between, are necessary for decision-making, and thus, ultimately, necessary for survival. Recent research indicates that in people who have experienced trauma and for whom survival, past or present, is an issue, the split between conflicting prompts can manifest in a split sense of self. An abused child, for instance, may exhibit paradoxical behavior, simultaneously clinging to and withdrawing from her abuser.

In her newest book, Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors: Overcoming Internal Self-Alienation, Dr. Janina Fisher helpfully presents a neurobiological map of early trauma’s negative effects on the communication between the right and left brain hemispheres and shows how this can lead to a lack of integration between the functions of each. This functional “splitting” can make us feel as if we have two brains, one under the direction of a traumatized part that originated in a painful experience, the other part guiding us toward normal responses to the day-to-day world.

Dr. Fisher has observed that many of her trauma clients speak of being “hijacked” by responses triggered by memories or perceived threats in the present moment. She writes:

“Characteristically, while the going on with normal life part tries to carry on (function at a job, raising the children, organizing home life even taking up meaningful personal and professional goals), other parts serving the animal defense functions of fight, flight, freeze, submit, and “cling” or attach for survival continue to be activated by trauma-related stimuli, resulting in hypervigilance and mistrust, overwhelming emotions, incapacitating depression or anxiety, self-destructive behavior, and fear or hopelessness about the future.”

Marci Gittleman, a psychologist in Madison, Wisconsin who works with trauma in her clinical practice, asserts: “Trauma often raises parts of ourselves, pushes other parts down, and separates parts of ourselves from each other. Recovery from trauma helps to welcome all of the different parts of ourselves into consciousness—even if we like some parts better than others!”

The traumatized “part” might be considered an unreliable narrator, pumping us with stress hormones that distort our awareness of reality. Trauma corrupts the telling consciousness that has been damaged by tragedy.

In a mindful approach to healing inner fragmentation and compartmentalization, we might acknowledge our multiple parts and discern who is telling the story (some research indicates that we are all multi-conscious rather than uni-conscious); acknowledge the source (traumatized child, veteran, shooter survivor); and ask if the information being given is valid.

Looking at fiction can help us understand how who tells the story shapes the narrative, and therefore shapes how we feel about what has happened. As we read, we might ask ourselves, who owns this story? How is reality being filtered through this consciousness (narrator)? Using one of the foundational stories of Western culture as an example of how meaning and interpretation vary with differing points of view, let’s look at different versions of the story in Genesis of the first human couple.

Adam’s version of the expulsion from Eden might include a description of the satanic snake, despair and betrayal over a temptress mate, his remorse and anger at being duped. Imagine Eve’s version as a woman pissed at taking the blame.

The same sequence of events narrated by the snake might emphasize Adam and Eve’s naiveté and the snake’s desire to wise-them-up by offering up a bite of fruit. Now imagine the story from a third teller, the archangel Jophiel, who led the couple out of paradise. His tale might be packed with the difficulties of being God’s messenger, his questioning of divine authority, his sympathy for the banished pair. Each version of the story would be accurate according to the experience of the teller, their truths part of a larger truth.

So, too, all aspects of the self, including the shameful and wounded parts, are worthy of having a voice; each deserves respect. Injury and self-harm occur when emotional pain is shunted into the borderlands of consciousness. To speak and to be heard, to be witnessed and bear witness is to shed the mantle of victimhood and embrace agency, dignity, and self-empowerment. These abstract words take on life and meaning when dramatized through characters in a story.

As an experiment in relating mindfully to the storm of conflicting impulses within us—with the goal of externalizing troublesome inner voices—try this:

1. Grab a pen and notebook, or sit at your computer. Close your eyes and breathe. Center yourself in your body. Open your eyes and begin.

2. With curiosity and playful creation as your guides, choose a specific troubling event in your life (you needn’t choose the most painful or difficult episode) and tell the story from your own point of view.

3. To objectify the narrative, consider using your name in place of “I.”

4. Now tell the same story from another person’s perspective, someone engaged in the situation, or a bystander, or even from an observing inanimate object like a tree. Use as much sensory data as possible: what is seen, smelled, touched, heard?

5. Compare the stories. What differences do you notice? What has been emphasized or left out in each? Can you name the prevailing emotion in each story? What feelings come up as you read them? What have you learned?

6. Take 15 minutes to write your responses beneath the stories.

The influential and ground-breaking American poet and essayist Walt Whitman wrote:

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

Elsewhere, Whitman wrote,

Stop this day and night with me and you shall

possess the origin of

all poems . . .You shall listen to all sides and filter them

from your self.

In healing from trauma, we might take our cues from this great poet by gathering our inner tribe, including the exiles, and validating their worth.

Psychologist Gittleman offers hope:

“I think of trauma like a perfect storm—it’s random, surprising, time stops, and life becomes different after the trauma from what it was before it happened. Trauma rocks the heart, body and soul—sometimes more, sometimes less, and different for you than for me. It can be hard to feel safe, and the impact reverberates into the present and future in ways that are both known and unknown—even if we decide we are not going to let it! Our best shot as survivors, however big or small the traumas, is to own our stories, and all of the different parts, over time, when we are motivated and ready, by ourselves and with others whom we have come to trust.”