Beauty

Meaning, Faith, and the Life of Pi

A conscious choice between hopelessness and faith is the spine of this story.

Posted November 26, 2012 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- "Life of Pi" is not actually about wrestling with a physical tiger, but a metaphoric one—with questions of meaning and faith.

- The characters in "Life of Pi," like in any dream because film is essentially collective dreaming, are all actually components of the self.

- The most important component of the self represented in "Life of Pi" is the raft, which represents the main character's faith.

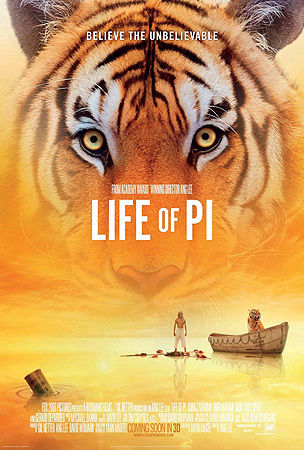

Based on the best-selling novel by Yann Martel, this bold and remarkable film is an adventure set in the realm of magical realism and centers on an Indian boy named Pi Patel, the son of a prudent and cautious zookeeper. The film is directed by Ang Lee, who brought us the breathtaking romantic swordplay in "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon"—which won 10 Oscar nominations, becoming the first Asian film and only the seventh foreign-language offering to ever get a nod for Best Picture.

But first, for the very few who haven't seen the film or read the book—spoiler alert! Don't read this unless you've seen or read the Life of Pi.

In the story, which starts with the obligatory cute prologue about an precocious boy, the family decides to move from India to Canada, bringing many of the animals with them. When the freighter carrying the family hits a storm, the stage is set for the main act—Pi is left adrift on a 26-foot lifeboat, lost in the Pacific Ocean, in the company of a zebra, a hyena, an orangutan, and a 450-pound Bengal tiger named Richard Parker—all vying in a grim competition for survival. It should be noted that this project has long been considered unfilmable due to the concept, as a long line of directors (including M. Night Shyamalan) were attached to the project and every single one jumped ship.

In terms of production challenges and a tightly constrained budget, Ang Lee was forced to wrestle with a tiger of his own. Shooting on water can literally drown a production in problems, delays, and cost overruns—just look at the tribulations of Kevin Costner, who flopped with Waterworld after burning through a $175 million budget. To pull off the film’s extensive aquatic sequences, the filmmakers had to build the world's largest self-generating wave tank.

Now, here’s the masterstroke of innovation—Lee decided to embrace 3D, even after a relatively fruitless foray into special effects with The Hulk franchise. Here’s why it was a spectacularly gutsy move to rely so heavily on computer graphics—3D has always lent a subtle artificial quality to imagery that prevents the suspension of disbelief.

In the computer animation business, the most pronounced form of this effect is called the “Uncanny Valley.” It’s a hypothesis by Japanese robotics professor Masahiro Mori, who proposed that when human replicas look and act almost, but not quite perfectly, like actual human beings, it causes an enteric response of revulsion; the "valley" refers to a dip in a graph of the comfort level of human observers.

However, the success of CG in films like Rise of Planet of the Apes likely encouraged Lee to bet that the technology would be ripe for animating subtle emotional reactions in animals. That bet paid off. Not only were the orangutan and tiger exquisitely portrayed in terms of facial emotions, like an orangutan pensively looking over the sea thinking about a lost child. The filmmakers even did motion capture on four real-life tigers who were on set. Also, 3D is ideally suited for rendering a hypnotically beautiful roiling sea.

As a result, the film dramatically renders the distance between Pi and the tiger, the restricted space of the lifeboat, and the overwhelming endless horizons of the ocean all around them. For this reason, this rare film adaptation is actually more entertaining than the book. However, Lee never tries to show off with those digital effects; he controls them with a firm hand, forcing them to serve the telling of the story unobtrusively. Incidentally, I’ve sailed, and no film has better captured the suffocating, claustrophobic feeling of a storm or the perfection of a graceful night sailing through a warm and welcoming sea.

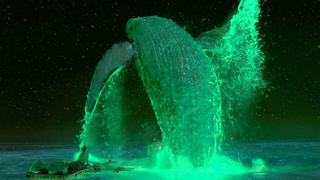

The director treats us to some truly magical images filled with majestic whales and the reflection of a tapestry of stars over a calm and peaceful sea. This is computer graphics taken to the level of visual poetry, a demonstration of what the medium can do if you let your imagination run free, that goes far past Avatar and Hugo. This film is an artistic triumph that rivals masterpieces like Kurosawa’s Dreams and Bertolucci’s Stealing Beauty in terms of cinematic genius.

Just as the exquisite beauty of the ocean is revealed just beneath the drama unfolding on the lifeboat, the true meaning of the film lies gently beneath the surface of the story. The story is so moving that even President Barack Obama, in a letter to the author, described it as "an elegant proof of God, and the power of storytelling."

To understand the jewel of wisdom buried deep within the story, which is pronounced to be “a story that will make you believe in God,” we need to understand that the story is actually about wrestling not with a physical tiger, but metaphoric one—with questions of meaning and faith. This story is a Gedankenexperiment for the worst-case scenario, a modern-day story of Job, all about how you can find spirituality and the meaning of life in the throes of all that is horrible and terrible in the world today. It is by surviving and making sense of all that goes wrong in the world, that uncovers the meaning of man.

The moral of the story is pretty clear and revealed at the end when Pi is forced to tell an alternate version of the story to Japanese investigators—with a sailor with a broken leg, a French cook, Pi, and Pi’s mother. Eventually, we realize that the zebra is the sailor, the hyena is the cook, and the orangutan is Pi’s mother, and the tiger, Richard Parker, is actually Pi. The details of cannibalism and savagery are gruesome. Finally, Pi simply asks the author, “Which story do you prefer?”

Clearly, Pi preferred the better story, a massive extrapolation of positive thought, that leads him to make sense of things, and that carries him to a new life with a loving wife and family. The other story, where humans are reduced to primal terror, could lead only to a brutally shattered life. In this story, you could see the entire story as an abandonment by God; but at the same time, it becomes evident that God was actually present at every moment. And in the end, he realizes that Richard Parker is actually his savior.

Richard Parker’s real name, lost due to a clerical error, is “Thirsty.” And where else, besides being lost in a life raft in the middle of the ocean, can you be surrounded by water and still die of thirst? In the same way, God is actually all around us, and still, so many of us are unable to receive the manna of heaven. In Hindu culture, water symbolizes the "ocean of life,'" with all living creatures existing as one contiguous body. The sea torments Pi with waves, threatens him with sharks, and even robs him of his family. At the same time, the sea also gives him life. It rains flying fish upon him, it grows a magical garden of algae, and in the end, bestows the gift of wisdom. Even Pi’s proper name, Piscine, is after a swimming pool—an object built to hold water, the water of spirit and God.

The characters in the Life of Pi, like in any dream because film is essentially collective dreaming, are all actually components of the self. At a higher level, the Tiger is Pi’s primal self, the orangutan represents universal love—as demonstrated by a protective mother, the brutal hyena is the malevolent cook who is the shadow, and the timid zebra is a young sailor with a broken leg, which represents the innocence of youth and the first to die. All are essential for becoming who we are.

However, the most important component of the self is the raft, which represents his faith. It is something that he has to construct by himself to be effective. The throughline, the spine of this tale, is that it is his raft that never forsakes him. More than any other part of the tale, it is the invisible force that finally brings him to safety and the force that transforms him into the individual he finally becomes.

Our challenges are what help to define us; what guides us to become more. What greater challenge can there be than trapped with a ferocious tiger? More so if that tiger is your own fear, anxiety, depression, desolation, and despair. It is our faith that helps us cross the cruel and endless sea. This is a message for all entrepreneurs and innovators as well, never give up your faith—faith in yourself, faith in your vision, faith in a better world.

In the final analysis, just as pi is a mathematical construct that can never be fully comprehended, the Life of Pi is essentially unfathomable; as is the battle between religion, science, and spirituality. However, just as Pi finds peace within—“Solitude began. I turned to god. I survived”—perhaps the final message of the film is one that simply urges us to find peace within as well.