Coronavirus Disease 2019

Coronavirus and the Wisdom of Others

How a deficit of everyday American altruism might be killing us.

Posted October 19, 2020

In the United States, we now find ourselves at the precipice of the third wave of the coronavirus pandemic. Having already documented 8 million infections and more than 215,000 deaths, public health experts worry that the fall and winter will bring substantially more infections and, sadly, more deaths. Dr. Michael Osterholm stated last Sunday on NBC’s Meet the Press that … "the next six to 12 weeks are going to be the darkest of the entire pandemic."

This grim forecast begs the question: How can we learn to live with a deadly virus that is here to stay? Is there something that we can learn from our life-changing pandemic experience, something that will make life a little bit sweeter in the post-pandemic future?

Perhaps we might find some answers to these existential questions if we look at the “surprising" African response to the coronavirus pandemic. The nations of sub-Saharan Africa have somehow been spared from the most devastating aspects of COVID-19. The CDC reports that in the Republic of Niger, perhaps the poorest nation in the world, as well as the site of my anthropological field research among the Songhay people, there have been just 1,209 reported cases of COVID-19 and only 69 deaths.

Given a general lack of medical infrastructure and widespread poverty, you would think that people in African countries like Niger would be dying in much greater numbers. But that does not seem to be the case. Consider Karen Attiah’s opinion piece in the September 22 edition of The Washington Post in which she wrote:

After the Ebola pandemic, Senegal set up an emergency operations center to manage public health crises. Some covid-19 test results come back in 24 hours, and the country employs aggressive contact tracing. Every coronavirus patient is given a bed in a hospital or other health-care facility. Senegal has a population of 16 million but has only 302 registered deaths. Several countries have come up with innovations. Rwanda, a country of 12 million, also responded early and aggressively to the virus, using equipment and infrastructure that was in place to deal with HIV/AIDS. Testing and treatment for the virus are free. Rwanda has recorded only 26 deaths.

As the United States approaches 200,000 deaths, the West seems largely blind to Africa’s successes. In recent weeks, headline writers seem to be doing their hardest to try to reconcile Western stereotypes about Africa with the reality of the low death rates on the continent. The BBC came under fire for a since-changed headline and a tweet that read “Coronavirus in Africa: Could poverty explain the mystery of low death rate?” The New York Post published an article with the headline, “Scientists can’t explain puzzling lack of coronavirus outbreaks in Africa."

In the October 14th edition of The Hill, Dr. Steven Phillips, a physician and epidemiologist, put the African COVID-19 experience in a broader context. He wrote:

Let’s put this into a global perspective. The global share of COVID deaths to share of the global population is 5 for the U.S., 2.3 for Europe, and 0.26 for Africa.

Scientists, health experts, and policymakers within and outside the African continent have struggled to find answers for this stunning observation of an exponentially lower than expected Africa virus toll. Finding solutions to this puzzle will have dramatic implications—not only for Africa but also for the rest of the world.

There is no shortage of scientific hypotheses to explain the dearth of COVID-19 infections in sub-Saharan Africa: the lack of testing, potential genetic factors, a high percentage of young people in the population, the preponderance of outdoor social activity, and strict government containment policies. According to Dr. Phillips, none of these ideas provides an adequate explanation for the relatively limited degree of COVID-19 infections and deaths in African nations.

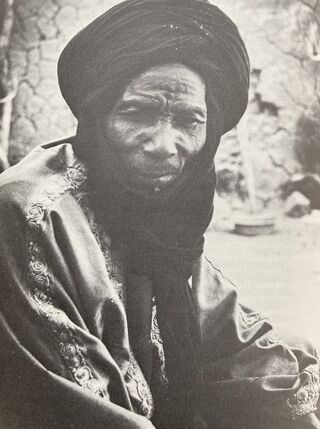

Let me offer an anthropologically contoured set of ideas. Social relations in places like Niger are very different from those practiced in the United States. In Niger, for example, where Songhay people have long faced the ravages of poverty (hunger, lack of sanitation, premature death from scourges like malaria, bilharzia, river blindness, cholera, and meningitis), most Songhay people have confronted everyday hardship with grit, determination, and a collective spirit.

In a place where hunger is common, people prepare more food than they need. When a person walks by a rural compound in Niger, they are routinely offered food. When there are food shortages in famine years, stockpiled grain reserves are given to families without resources. When there are floods, neighbors give what they can to those who lost their homes. When a person becomes seriously ill, neighbors will collect money to fund her or his treatment. Although some of these altruistic and charitable behaviors are common in the U.S., they are not, I would argue, baked into the routines of everyday life. In Niger, altruism is a necessary and sufficient antidote to poverty and its brutal existential challenges.

Taking note of everyday African altruism brings us back to the U.S., where we have the terrible prospect of a COVID-19 third wave that will bring widespread suffering and death to people in our society. How do we respond to such a crisis? Many people, including many officials in powerful government positions, say:

“Let the virus spread. Let it rip so we can achieve herd immunity.”

“Let the old and sick die so we can see our way to a post-pandemic future.”

Such are the sentiments of an ever-increasing number of people in the U.S.—the strong (more often than not white folks) will survive, and the weak (more often than not the old, the sick, and People of Color) will perish. In the end, this process will purify our population, making it stronger and more “fit.”

In all my years of living in West Africa, I never observed the socially destructive ramifications of such ideology, the intolerant and racist attributes of which have historically brought much destruction and death.

In this moment of crisis, is it not time to wake up, open our eyes, and learn from the altruistic wisdom of Africans?