Anger

Recognize Rage: The First Step in Outsmarting Anger

There’s nothing wrong with anger. It’s what you do with it that matters.

Posted March 12, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- Learning to control anger requires shifting into the brain's pre-frontal cortex (PFC) which houses emotion regulation.

- Shifting into your PFC requires that you recognize feelings of rage before you act on them.

- To better recognize rage, use a 1 to 10 scale (10 being the angriest) and beware if you go beyond a 6.

To “recognize rage” sounds simple. Of course, you can tell when someone is angry. It’s obvious right? You’ve seen people scream at the customer service desk, or felt the ire of fans when the ump makes a bad call or had someone yell at you with or without reason. While universally viewed as socially unacceptable, aggression and “bad tempers” run rampant in our daily lives. Small angers can lead to snippy remarks. Large angers can lead to murder or war. Each of us probably experiences at least a little anger every day. Remarkably, however, most of us do not maim or kill each other regularly. We have, over time, found a way to control those primitive, murderous rages we inherited from our ancestors.

But do we really recognize the full spectrum of the anger response or just the outburst or “tip” of the iceberg? Why don’t we ever seem to notice before someone suddenly “snaps?” And how many of us can really recognize details of our own anger response? Have you ever impulsively said something mean and harsh, perhaps biting and condescending? Have you ever slammed a door, broken a dish, or kicked a vending machine? Have you ever hit something or someone? Those are aggressive acts fueled by anger. But when did your anger start and how did you fail to control it?

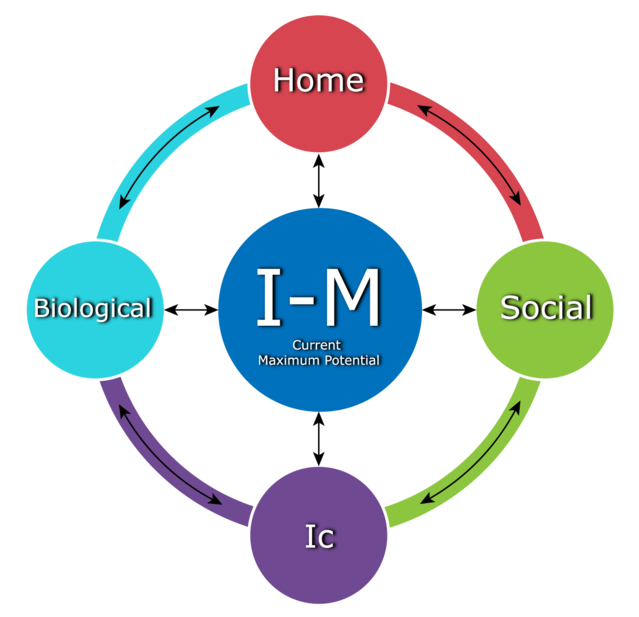

While we are indeed born to experience the emotion of anger, the fact is, recognition of anger and what do with it comes much later. The reasons for this are twofold. First, anger is an emotion with a wide spectrum ranging from mild annoyance to aggravation, all the way up to boiling rage. Secondly, while we are born with the ability to experience and act out on our anger, we are not born with the instant ability to monitor our anger response, or to “take it down a notch.” The ability to modify our emotions, particularly anger, is actually pretty sophisticated and comes with the brain’s biological growth and especially the development of the PFC, where our emotional regulation is located.

Imagine a child’s tantrum over a trinket. As an adult, we may wonder why a child may become so angry over what seems so insignificant. But that trinket is not insignificant to the toddler. From their point of view, it seems a critical and vital resource. From a brain perspective, the child’s PFC is relatively immature, and their limbic emotional brain is more dominant. But in an anger situation, no matter how old your brain may be, that limbic, emotional, impulsive portion always has the potential to take over and launch your rage. Anger control happens when you shift back to the PFC, and that is why the first step in managing your anger is to recognize that you are angry at all. Recognition is a function of the PFC.

When you “recognize rage,” you learn to use your PFC to identify the feeling of anger within yourself well before you act. Whether it’s irritation at a late train, vexation over a slow Internet connection, or infuriation with a colleague, the ability to pinpoint our limbic anger is a decisive determinant of success. Although controlling the limbic system is not necessarily innate, the brain tools are all there just waiting to be trained and developed. When you tap into this strength, you can learn to identify this powerful emotion in others as well, often before they act. Whether it’s you or someone else, it’s key to remember that the loose cannons in life don’t usually get what they want in the long run. The sooner you learn how to recognize rage, the sooner you’ll be able to slowdown that emotional freight train and prevent a regrettable, even tragic act — yours or that of another person.

How do you experience this most basic of human emotions? Do you recognize your own anger but keep your cool? Or does your face get flushed and your muscles tense up? Do you feel and recognize anger but don’t express it? Perhaps you are a person who knows you are angry and lets everyone else know it too, getting upset and turning up the heat around you. Maybe you don’t react at all, even if you feel a little angry. Or perhaps you are not even aware that you are angry, but your body knows and reacts, being more aggressive, having a shorter fuse, and generally quick to respond to any perception of insult.

The control of anger rests in our PFC, the thinking part of our brain. Two important neo-cortical functions are language and math, and this self-help tip uses both to exercise your pre-frontal cortex. Let’s look at language first. Think about the wide range of words that we use for the various degrees of anger we can experience: irritation, fury, vexation, annoyance, frustration, anger, impatience, aggravation, displeasure, disgust. Of course, anger has many other creative names, including pissed, heated, ballistic, postal, ticked.

A simple self-help exercise you can do to begin to outsmart your anger is to construct your own personal anger scale. Feel free to use some of these words and any others you come up with. Once you have your list of 10 words, assign each a number according to its intensity for you. My own personal scale from 1 to 10 (10 being the angriest) is: irritation, aggravation, annoyance, frustration, impatience, displeasure, anger, wrath, fury, and rage. In creating this word scale we combine language and math, firmly shifting the nexus of control to the PFC.

Recognition itself is a thinking task, and it is important to recognize these nuances of anger. We experience levels 1 to 5 on my scale as human beings every day. But be wary if your anger burns into the range of 6 and above. Anger that shifts beyond 6 carries a much higher risk for true conflict, for verbal fights and aggression, and even physical violence. Above 5, your limbic system begins to overwhelm your PFC. By keeping yourself below a 5, you can normally use your cortical control and keep your anger under wraps. As recognition is a thinking function, it keeps your PFC well exercised, while exorcizing your limbic “logic” that tells you to just fight and get it over with. With this exercise, you are shifting the locus of control from the limbic system into the PFC, exactly where you want to be to outsmart your anger. Keep it frontal. Don’t go limbic.

You have a lot to lose when you’re not able to recognize rage. Unrecognized rage can lead to loss of resources, residence, relationships, opportunities, respect from peers, and much more.

Recognize rage.

There’s nothing wrong with anger. It’s what you do with it that matters.

References

Outsmarting Anger: 7 Strategies for Defusing our Most Dangerous Emotion. Joseph Shrand, MD, Leigh Devine, MS Second Printing 2021 Books Fluent Press