Play

How Real Are Ghosts, Aliens, and Spirits?

Are there rational explanations for the strange things we see and sense?

Posted September 16, 2018

Updated May 31, 2020

One patient in a psychiatric hospital, a black woman, always covered her face with white makeup because she believed she was an angel. She also missed her late husband terribly. From time to time she claimed she could still see him. “I can feel him — you know, like he’s still around. One morning I woke up and I saw him — standing by the wardrobe — a ghost.”

History thought ghosts were real

Throughout history, ghosts were accepted as a given. Shakespeare and his contemporary dramatists featured them liberally. Macbeth reacts to Banquo’s ghost, and the ghost of Hamlet’s father sets in motion the action of that play. As culture became more scientifically minded, seeing ghosts came to be considered more of a psychological phenomenon. Readers took the three ghosts in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, for instance, as figments of Scrooge’s imagination rather than actual disembodied spirits.

But just because something is psychological doesn’t mean it isn’t real to the person who experiences it. Scrooge’s encounters change him profoundly. The grieving widow above wanted to feel her husband’s touch again, hear his footfalls and the sound of his voice. She even wanted to have sex with him again. Her unconscious mind wasn’t about to recognize death as an obstacle to her wishes.

Imagination is more powerful than people realize

For centuries hallucinations such as seeing ghosts were used as proof of madness, an objective marker of mental abnormality. But what people typically think of as objective reality is in fact a compromise. A one-to-one correspondence between outer reality and inner brain events does not exist. Outside stimuli impinge on sense receptors, and the brain then interprets the results. This makes reality subjective through and through.

Each eye has a blind spot located about 18 degrees off to either side if one is staring straight ahead. Normally the eyes are also in continuous but imperceptible motion (ocular jitter) so that the light receptors in the retina experience continual boundary changes between light and dark. The retina’s detection of light boundaries and changes in contrast are among the earliest elements in a series of events that build in complexity to create the sensation we call seeing.

The eye is not a camera

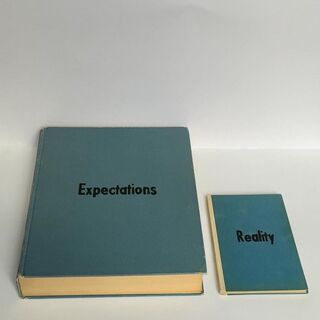

Unlike a camera that indiscriminately records everything in its field of view, the retina is highly selective in what it passes on to the brain downstream. Compared to the sharp acuity of central vision provided by the fovea (20/20), peripheral vision is quite poor (20/400). We should see a shaky, blurry world of dissolving edges and missing parts. Instead, we see a panoramic scene that seems stable and in focus wherever we look. We see this picture because an enormous amount of unconscious editing took place before visual information even enters our awareness. The brain fills in gaps. It compensates for head and body movement. It makes educated guesses about what we’re looking at, and its editing is highly biased by expectations, history, context, and desires.

About 5 percent of adults experience occasional hallucinations but never seek medical attention. They go about their business and accept their hallucinations as a matter of fact. In elderly individuals who suffer some loss of vision, highly detailed, unemotional visual hallucinations are common enough that the phenomenon goes by the name of Charles Bonnet syndrome. Affected individuals see people or animals that they readily acknowledge aren’t there. Similarly, about a third of Americans claim to have seen angels, a proportion that may seem high but is consistent with the fact that a third of children have imaginary friends.

There is no reason why factors of bias, expectation, and desire should not play a similar role in individuals who claim to see ghosts, aliens or other strange entities. Critics are quick the dismiss the experience itself, when what it really at issue is that person’s interpretation of the experience. An individual may misinterpret the meaning of an unusual experience that is more often than not imbued with emotion, but that doesn’t make it any less real.

Send queries to neuroman@gwu.edu or to the links below to request a free copy of "Your Brain on Screens."

References

Frank Tallis, 2018. The Incurable Romantic and Other Tales of Madness and Desire. New York: Basic Books