Health

Humanizing Healthcare for LGBTQ People

An Interview with Dr. Evan Goldstein

Posted February 25, 2019

Dr. Evan Goldstein specializes in gay men's sexual wellness--with an integrative, individualized, holistic approach. The aim is to affirm sexual health, humanize medicine, and offer care tailored to and emerging from LBGTQ communities. According to Sarah Schon, of Harvard's T. H. Chan School of Public Health, "nearly a sixth of LGBTQ adults have experienced discrimination at the doctor’s office."

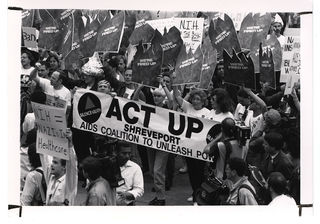

The problem is widespread, with serious consequences for people's lives and health. The mission of organizations like the National LGBT Health Center is to revolutionize healthcare so that it becomes truly inclusive. I talked with Goldstein about what this means on the ground, or in the doctor's office--how a medical encounter integrates the emotional, physical, social, and political. For too long gay men have faced stigma, prejudice, and taboos in traditional medicine. Goldstein's practice and his activist writing represent a movement to tailor care to particular communities and to educate the medical establishment on healthcare that affirms, rather than stigmatizing, LGBTQ people.

You’ve written quite a bit about LGBTQ affirming healthcare? What does it involve? How does it relate to what you call “elevated community care”?

LGBTQ affirming healthcare understands the psychological, psychosocial, and physical ramifications of being part of a specific community. Understanding these basic tenets allows for not only non-judgmental, non-biased care to be delivered, but also solutions that need to be tailored to specific needs in order to have improved outcomes. I describe this care as “elevated community care,” but, realistically, it should be everyone’s basic care. Without understanding the ins and outs of a community (pun intended), practitioners are doing a significant disservice to their patients.

There’s a social and political edge to LGBTQ affirming healthcare—emphasizing empathy and shared values as a way of mitigating stigma and judgment when it comes to both sex and health. Ultimately, the idea is to transform healthcare. Medicine is more effective when patients are comfortable seeking care and communicating openly. How do these goals shape your practice?

First and foremost, the experience actually begins when people go to make their first appointment. And nowadays most people Google the referred physician and/or the pathology at hand, all to gain a sense of the care that is going to be delivered. At Bespoke Surgical we have worked very hard to make the process easy, using appropriate technology for booking appointments and an extensive amount of community-appropriate literature that begins to build this trust before one even steps into our office. From that point, the office has been set up as an inviting space, with similar aesthetics as my own home, to provide an environment suitable for professional discussions on not-so-easy topics of conversation. And lastly, I do not view myself as anything more than a friend with knowledge as it pertains to sexual health.

With that in mind, I pass no judgment nor place any bias on anyone’s desires or demons. I simply discuss and analyze form, function, and aesthetics in a new way of thinking, specifically as it pertains to anal engagement. There is a complete science behind the behind, and these new scientific principles truly allow people to resolve their current limitations, creating successful partnerships - whatever they may be.

One thing that reinforces the approach I take (and the lack of similar options) is the fact that we are seeing a major uptick in clients flying in from other states and other countries—a large portion of these as second and third opinions. Over and over we see the same narrative being told to the client of “everything is fine” or “why do you give a shit how it looks?”. Clearly, there is something causing pain, discomfort, or other symptoms, like the aesthetics, limiting defecation and/or anal engagement, and without the specific knowledge, as it pertains to our community, successful evaluations and treatments are limited. Maybe I am too optimistic to think that everyone should have all of these sensitivities in their back pocket - but even if a proctologist is completely unfamiliar with anal engagement (and that’s OK - we all can’t be experts on everything), let’s at least set up an appropriate referral pattern to a physician with the knowledge to rectify the situation for everyone to optimize their worlds.

In the 1970s, medicine still bore the traces of the fact that homosexuality was classified as a mental disorder in the DSM until 1973. Then in the 1980s, stigmas around HIV and AIDS added another layer of discomfort to medical care for LGBTQ people. In 2019, the world has changed in so many ways--largely as a result of activism. How do you see medicine evolving to reflect those changes—or to make even more change?

Unfortunately, the change you mention has been quite slow, specifically as it relates to the sexual sciences. Even today, all the stigma associated with HIV and AIDS continues to influence the care that is delivered. I think the most interesting point for me is that although (most) people don’t view homosexuality as they did in the past, specifically in urban areas, this normalization has led many health care providers to unify everyone’s care, regardless of this difference. The problem with “lumping” together care is that it limits specialized and individualized care, which really prevents delivery of care that makes substantial improvements. What I do know is that the differences among us should not only be celebrated but also be used to guide highly specialized algorithmic care to the betterment of that specific client and community at large. Let’s take my world—the sexual practice. Without the knowledge and wherewithal in terms of how our community engages, the delivery of care is suboptimal with potentially serious consequences if not optimized to benefit the client in all aspects.

You tend to use everyday language and humor rather than medical terms in both your writing and your practice.

It’s my intent to humanize my profession. For far too long the white coat has created an unnecessary barrier between the physician and the patient. What happened to the days of developing a more personalized relationship?

The volume-based model, consisting of seeing the patient’s problem and then treating the patient’s problem (which is the current set-up across all of America), misses one important thing: the person behind the problem.

Thankfully, I was exposed to a more holistic, whole-body medical training through osteopathy, which guided me toward the power of psychology and the understanding of how a single ailment can affect the body beyond its origins.

Fast forward to my current practice--specifically specializing in sexual wellness. In order to embrace such topics and/or evaluate the nature of their complaint, the delivery of care must be personalized and truly bespoke (pun intended). But beyond that, because it is so taboo and not discussed openly, any forum that I display my editorial writing on needs to bring in this humanistic balance. I am first a person, second a father, and then a physician. And to accomplish my goals in advocacy and breaking down more barriers for our community, I need to set the stage of being human. My ideal is to combine real-life scenarios with medical and surgical professionalism in a harmonious way. More easily said than done, of course, but we are attempting, and hopefully succeeding.

What should all people know about anal physiology? Are there things certain particular people should know—men, women, trans people, gay, straight, bisexual, polyamorous?

It is my life’s mission to promote education at a young age to truly embrace sex and all it has to offer in its many diverse forms. And to encourage physicians to think beyond traditional ways of delivering care. It doesn’t work if we don’t talk about it and it certainly doesn’t work if we don’t have the providers trained in it.

You mentioned that what you call “elevated care” should be basic care for everybody. You specialize in working with the whole person—and personalizing care. You’ve written about impediments to this approach created by insurance-driven medicine in the U.S. This becomes a class issue. Some people can afford to seek out doctors who will treat them as people, but others don’t have much choice. What can medical professionals do to improve the situation?

First off, I pride myself in taking care of anyone that needs help, regardless of insurance or payment. Now, that’s just me, and many do not believe in the same model. With that said, I think attempts are being made to train physicians on the issues at hand for each community and how best to solve these issues. I do think any big corporate organization, like the hospital and health care systems, is limited, just like big corporations across the land. The cog in the wheel approach to delivering care is mediocre at best and I think it will be years and years before any substantial change is achieved. I hope that trainees can see our practice and realize that private practice isn’t dead and that the brainwashing system of hospitalized care gets called into question. But at the end of the day, it’s money and it’s asking America, which doesn’t yet fully embrace our community and lifestyle, to take on the issues wholeheartedly for the appropriate changes to be made. I am still uncertain, but I do plan to continue to encourage by writing and speaking out on all issues, especially the ones near and dear to my heart: the queer ones.