Neuroscience

Imagination Can Alter Real-Life Attitudes on a Neural Level

New research identifies a brain region that helps imagination change attitudes.

Posted May 17, 2019

"Above Us Only Sky" is a behind-the-scenes documentary about the making of John Lennon's classic 1971 album, Imagine, that is a new release on Netflix this month. An imagination-based study was published today by Daniel Schacter of Harvard University and co-authors Roland Benoit and Philipp Paulus of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognition and Brain Sciences. This paper corroborates that Lennon was spot on when he recommended using imagination to shift our worldview (e.g., "Imagine there's no heaven. It's easy if you try. No hell below us. Above us only sky.")

"Merely imagining interacting with a much-liked person at a neutral place can transfer the emotional value of the person to this place. And we don't even have to actually experience the episode in reality," Schacter said in a statement.

The music video for the song "Imagine" opens with a Grimm's fairy-tale-like landscape enshrouded by dense fog. Within a few seconds, the outline of two silhouettes walking down a path emerges. Soon it becomes clear that the viewer is observing a private moment between two iconic superstars from a voyeuristic vantage point, as John Lennon and Yoko Ono navigate the path ahead and make their way out of the forest.

The visuals and metaphors throughout this video evoke a wide range of emotions. On both a visceral and cerebral level, the opening scene of the "Imagine" video is eerie and kind of spooky—but also has a dreamy and romantic quality. The next location of the video is a serene white room that is darkened by wooden shutters that block almost all sunlight from entering the mostly-empty space. As Lennon plays the piano and sings "Imagine," Ono walks with Zen-like grace from window to window, slowly opening the blinds and allowing daylight to stream into the room.

As you can imagine, opening all the window blinds changes the whole vibe of the room. Now that I've described the video and you've conjured up these images in your imagination, please take few minutes to watch this fifty-year-old video that was shot on location at their home in Tittenhurst Park with a "This Is Not Here" sign above the front door.

The latest neuroscience-based research shows that our real-life attitudes can be reshaped by what our brain imagines. This paper, "Forming Attitudes via Neural Activity Supporting Affective Episodic Simulations," was published May 17 in the journal Nature Communications.

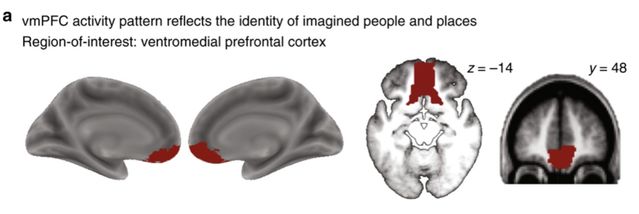

The findings of this state-of-the-art research on the power of imagination suggest that real-life attitudes are influenced by what we imagine. From a neuroscience perspective, based on fMRI brain imaging performed during their investigation, the researchers speculate that the ventromedial prefrontal cortex plays a pivotal role in facilitating the power of imagination.

When you brainstorm about geographic locations tied to strong emotions—what specific places spring to mind? If you suffer from avoidance behaviors that cause you to steer clear of certain locations because of negative emotional associations, there is good news: Real-life attitudes about specific places can be reshaped by imagining being in that place with a much-liked person, according to this new study.

In the Discussion section of their paper the authors write:

"Our hypothesis assigns a key role to the vmPFC in mediating such presumed attitude change. This region has been shown to integrate similar memories into schematic representations of the elements that are shared across those memories. The concurrent reactivation of disparate representations, in turn, can support simulations of even novel experiences.

The vmPFC may thus code for affective representations of elements from our environment that can be flexibly integrated to support affective episodic simulations. Here, we hypothesize that such simulation-based integration induces experience-dependent plasticity in the neuronal coding of the individual elements. This plasticity could then enable the transfer of affective value from one element (i.e., the unconditioned stimuli) of the episode to the other (i.e., the conditioned stimuli)."

In the first part of this study, participants were asked to list the names of some people who they liked very much and also to list the names of people they did not like. During this phase of the experiment, they were also asked to list specific places that had neutral emotional associations.

During the next phase of the experiment, participants were asked to vividly imagine spending time with a much-liked person in an emotionally neutral location while lying in an fMRI brain scanner. The brain scans allowed researchers to determine if a participant's real-life attitude towards a neutral place had changed after imagining being in that location with a much-liked person.

An analysis of this fMRI data illuminated specific neural activity associated with imagination influencing real-life attitudes in the brain. As mentioned, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex appears to play an essential role in this process. "We propose that this [brain] region bundles together representations of our environment by binding together information from the entire brain that form an overall picture," Benoit said in a statement.

You might be asking, why is this international team of researchers interested in the phenomenon of imagination reshaping real-life attitudes? A press release from the Max Planck Institute addresses this question: "They want to better understand the human ability to experience hypothetical events through imagination and how we learn from imagined events much in the same way as from actual experiences. This mechanism can potentially augment future-oriented decisions and also help to avoid risks."

Benoit also emphasizes how these findings might help people overcome avoidance behaviors or the consequences of negative thoughts. He said, "In our study, we show how positive imaginings can lead to a more positive evaluation of our environment. I wonder how this mechanism influences people who tend to dwell on negative thoughts about their future, such as people who suffer from depression. Does such rumination lead to a devaluation of aspects of their lives that are actually neutral or even positive?" Answering this question will most likely be the next line of investigation explored by scientists in the Schacter Memory Lab at Harvard and the research labs of Benoit and Paulus at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Germany.

References

Roland G. Benoit, Philipp C. Paulus, and Daniel L. Schacter. "Forming Attitudes via Neural Activity Supporting Affective Episodic Simulations." Nature Communications (First published: May 17, 2019) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-09961-w