Flow

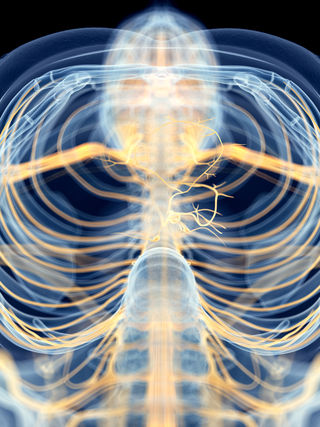

The Psychophysiology of Flow and Your Vagus Nerve

Vagus nerve survival guide: Phase eight.

Posted May 31, 2017

This Psychology Today blog post is phase eight of a nine-part series called "The Vagus Nerve Survival Guide" which is designed to help you stay even-keeled in a topsy-turvy world. Each of the nine vagal maneuvers I've curated for this series can help you hack into the power of your vagus nerve in ways that will reduce stress, anxiety, anger, egocentric bias, and inflammation by activating the "relaxation response" of your parasympathetic nervous system. A variety of "self-distancing" techniques have also been found to reduce egocentrism and improve vagal tone (VT) as indexed by heart rate variability (HRV).

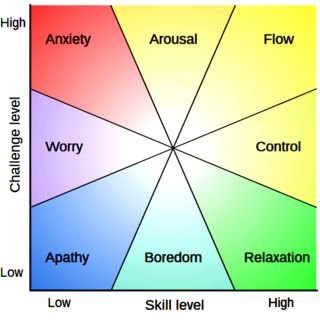

Interestingly, the latest empirical evidence suggests that there is a correlation between parasympathetic engagement of the vagus nerve and creating a "flow state." Flow is a blissful and rewarding state of consciousness that feels good and occurs when a person "loses" him or herself wholeheartedly in an activity. Most simply put, flow tends to occur when you find the sweet spot where your skill level perfectly matches the challenge while doing any type of activity. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi coined the term "flow" in his seminal book, Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play (1975).

From a psychophysiological perspective, flow is a state of "relaxed but heightened arousal" marked by a situationally perfect "yin-yang" balance within the two branches of your autonomic nervous system (ANS). This dynamic duo includes the "fight-or-flight" mechanism of your sympathetic nervous system and the "tend-and-befriend" or "rest-and-digest" mechanisms of the parasympathetic nervous system.

A few weeks ago, I wrote a Psychology Today blog post, "Superfluidity and the Transcendent Ecstasy of Extreme Sports," which explored the parallels between heightened experiences of flow during endurance sports and moments of secular and religious ecstasy explored by Marghanita Laski in the 1960s. This blog post was inspired by a May 2017 study, "Evoking the Ineffable: The Phenomenology of Extreme Sports," that was published in Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice.

From the perspective of this vagus nerve series, a recurring theme has been the link between parasympathetic activity being part of a feedback loop that is often rooted in a smaller sense of self and reduced egocentric bias. According to the latest research on the phenomenology of extreme sports, a spiritual type of "overview effect" (when astronauts witness Earth from space and realize the oneness of humankind) occurs during sports when someone is in the flow channel and experiences such intense awe that it triggers a spiritual feeling of life-altering ecstasy. Notably, the word ecstasy comes from Greek and means "to stand outside oneself.”

High Positive Valence + High Arousal = Core Flow State + Ecstasy

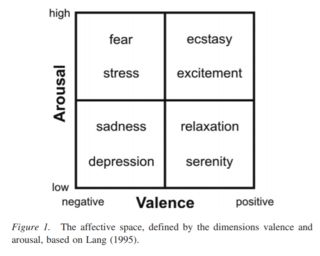

The research of Peter Lang, who is director of NIMH Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention (CSEA) focuses on the link between the brain, behavior, psychophysiology and emotions. Personally, as an athlete and coach, his research findings have been fundamental in helping me to cognitively understand why creating high positive valence and high arousal is key to tapping into a flow channel and "being in the zone" both on and off the court in ways that I can share with others.

In 1995, Lang published a landmark study, “The Emotion Probe: Studies of Motivation and Attention.” For this research, Lang used an emotionally based picture library to monitor various degrees of valence (agreeable/pleasant or aversive/unpleasant) and emotional arousal.

Lang's findings provide some empirical evidence which suggests that just about any stimuli that evokes positive valence and arousal (such as appreciating natural wonders, the arts, music, dance, etc.) can create a drug-free type of “ecstasy” that isn't dependent on mastering a particular skill or becoming a Jedi Master of something.

What images or paintings evoke both high valence and high arousal for you in ways that could "take you away" and allow you to “stand outside yourself” for a moment? For me, just about every single painting by Caspar David Friedrich puts my emotions and consciousness in the upper right-hand corner of the "ecstasy" quadrant within Lang's "affective space" graphic above.

The Romantic-era painter, David Caspar Friedrich (1774-1840) was known for his deep, philosophical connection to the sense of wonder and awe that he experienced in nature. Friedrich found spiritual significance in the wilderness and was said to have religious "conversion experiences" during his excursions to the mountains and coastline.

As an artist, Friedrich was able to transfer the sense of awe he experienced in nature onto the canvas so that anyone (like us right now) viewing his paintings can still experience these positive emotions on a visceral level over a hundred years later. Whenever I look at the painting above, I'm reminded of William James' writings on The Varieties of Religious Experiences. James wrote:

“Religious awe is the same organic thrill which we feel in a forest at twilight, or in a mountain gorge; only this time it comes over us at the thought of our supernatural relations; and similarly of all the various sentiments which may be called into play.”

I actually have a cheap (but beautiful) reproduction of the Landscape in the Riesengebirge hanging on my bedroom wall. Looking at this painting always fills me with a perfect blend of optimistic tranquility combined with a comforting sense of my own "small self" in the grander scheme of things. The vibe of this painting never fails to take the pressure off and calm me down while lifting my spirits at the same time. Based on extensive research, I have a hunch this unique blend of varying positive emotions is most likely tied to the psychophysiology of my autonomic nervous system and vagus nerve.

In 2015, Paul Piff and colleagues from the University of California, Irvine reported that experiencing a sense of awe promotes altruism, loving-kindness, and magnanimous behavior. The study, “Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior,” was published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Piff and colleagues described awe as “that sense of wonder we feel in the presence of something vast that transcends our understanding of the world.” They point out that people commonly experience awe in nature, but also feel a sense of awe in response to religion, art, music, etc.

For this study, Piff et al. conducted various experiments to hone in on and examine various aspects of awe. Some of the experiments measured how predisposed someone was to experiencing awe. Others were designed to elicit awe, a neutral state, or awe-aversive reaction. In the final and most pivotal experiment, the researchers induced awe by placing individual study participants in a forest filled with towering eucalyptus trees. In a statement to the University of California, Piff described his research on awe saying:

Our investigation indicates that awe, although often fleeting and hard to describe, serves a vital social function. By diminishing the emphasis on the individual self, awe may encourage people to forgo strict self-interest to improve the welfare of others.

When experiencing awe, you may not, egocentrically speaking, feel like you're at the center of the world anymore. By shifting attention toward larger entities and diminishing the emphasis on the individual self, we reasoned that awe would trigger tendencies to engage in prosocial behaviors that may be costly for you but that benefit and help others.”

I write extensively about the psychophysiology of awe as linked to the parasympathetic nervous system in phase six in this vagus nerve series. The main takeaway of that Psychology Today blog post, “Awe Engages Your Vagus Nerve and Can Combat Narcissism,” is that jaw-dropping moments of awe seem to create a type of “wow!” that stops you dead in your tracks. The hypothesis of some researchers is that the finely-tuned homeostatic balance within your ANS elicited by awe creates self-distancing and reduces egocentrism in ways that allow someone to soak up all the details of important and often complex information from the surrounding environment in a memorable way.

Michelle "Lani" Shiota is founding director of the SPLAT (Shiota Psychophysiology Laboratory for Affective Testing) at Arizona State University. She's also a trailblazing pioneer in the study of the psychophysiology of awe. Her 2007 study, "The Nature of Awe: Elicitors, Appraisals, and Effects on Self-Concept," laid the groundwork for the past decade of scientific research on awe.

In my aforementioned Psychology Today post on awe, I discuss a lot of the science involved in the clinical research about awe. In this post on flow, I wanted to revisit the lecture Shiota gave on “Awe and the Mind and Body” again because in the first part of this lecture she wears her “scientist hat”... But in the second part of the lecture (where the video below is cued to begin), Shiota puts on what she refers to as her “artist” hat and discusses how awe manifests itself while listening to music or experiencing other types of creative expression associated with flow. Please take a few minutes to watch this section of Lani Shiota’s lecture in this YouTube clip:

During this lecture, Shiota hypothesizes that when the parasympathetic nervous system creates a relaxed but semi-exuberant state of homeostasis that it's easier for someone to let his or her guard down while simultaneously being more receptive to nuanced complexities of an "awe-inducing" experience such as flow.

My goal with this nine-part vagus nerve series is to pinpoint the role that the parasympathetic vagal system plays in universal human experiences that are rooted in our common, everyday psychophysiology. And to create actionable advice for people from all walks of life so that anyone can hack into his or her ANS by using a variety of easy vagal maneuvers that fit someone's lifestyle.

As a first-person example, going to dance clubs has always been a welcomed opportunity for my brain to stop thinking about my day-to-day life and get some exercise while bonding with friends and total strangers in a festive environment expressly designed to have fun.

As an educated guess, I suspect that the Travolta-esque "vagal maneuver" of going out "disco dancing" triggers many of the same parasympathetic responses I've been exploring throughout this vagus nerve series. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of clinical research or empirical evidence on this topic. So, I decided to share some purposely unacademic and kind of quirky anecdotal findings based on going out dancing this past weekend. I had a blast. And the experience gave my vagus nerve exactly the type of stimulation it needed at this point in time.

For some narrative background: Since 1988, I’ve spent countless nights boogieing in the exact same spot on the dance floor directly in front of David LaSalle’s DJ booth at the Atlantic House in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Every Labor Day weekend for the past 30 years, David has given me a compilation of the "greatest hits" and A-house anthems of the previous summer. In early June, my friends and I are always eager to identify what the "song of the summer" is going to be. And we take bets.

A few days ago, on Saturday night of Memorial Day Weekend 2017, the A-House was packed with people celebrating the beginning of summer. I was crammed onto the dance floor like a sardine and loving every minute of it. Near the end of the evening, DJ LaSalle (who is also a reporter for Billboard) said that he'd just gotten the promo for the new Carly Rae Jepsen song “Cut to the Feeling” and told me he thought it was a contender to become the song of the summer.

What transpired over the next seven or eight minutes on the dance floor when LaSalle started playing the latest turbo-charged Jepsen song was kind of mind-boggling. "Cut to the Feeling" starts with a sound effect that twinkles like a shooting star and is clearly an ode to "Lucky Star" by Madonna. Then, the intro bops into a kind of unusual tribal drum beat section with sparse vocals which unexpectedly ends...and then...out-of-the-blue "Cut to the Feeling" explodes into one of the most infectious and uplifting choruses I’ve heard in eons. Sir Nolan, who produced this song, really hit it out of the park.

Throughout this "transcendence inducing" experience of pure-pop perfection Jepsen is singing, “I wanna cut through the clouds, break the ceiling. I wanna dance on the roof...take me to the stars. I wanna play where you play, with the angels.” It's a really jubilant song.

After hearing the chorus a couple times, it was clear that everyone on the dance floor at the A-House was hooked by this earworm and tuned into the same “psychophysiological” wavelength. We were all moving like one big amoeba without an ounce of self-consciousness or egocentricity at play. (As a side note: Through the lens of Barbara Fredrickson's work on "micro-moments" of feeling connected and simpatico with loved ones and strangers, this experience was off the charts.)

During the tribal drum sections of the song's bridge, everyone would stay huddled closer to the ground and stomp their feet in unison while forming mini conga lines. Then, when the chorus blasted off again, everyone would start jumping as high as they possibly could as if we all had rocket boosters attached to our Achilles' and were literally trying to "break through the ceiling" into the stratosphere and "play where the angels play." I haven't had that much fun in a long time and didn't want the song to end.

As is usually the case, this experience on the dance floor nourished a strong sense of social connectedness and community on a visceral and parasympathetic level and most likely improved everyone's vagal tone. Hopefully, this long-winded story will inspire you to go out dancing more regularly, if you don't already.

Now, let's get back to some more science-based research on music, the psychophysiology of flow, and the vagus nerve. Fredrik Ullén is a professor of cognitive neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden who studies elite-level performance and flow. He's also an internationally renowned concert pianist, which makes it easy for him to be a guinea pig in many of his own experiments.

Using music as a model, Ullén has done fascinating research on how the parasympathetic response might assist people in creating an optimal flow state to perform at a world-class level within a specific field of expertise. His 2010 paper, “The Physiology of Effortless Attention: Correlates of State Flow and Flow Proneness,” was published by MIT Press.

During this study, Ullén et al. found that when professional singers were compared to amateurs, it became obvious that professionals' heart rate variability (HRV) increased markedly, whereas no such increase was observed in the amateurs. This reflects a mixture of parasympathetic and sympathetic activity, with slightly more parasympathetic activity which increases vagal tone (VT) as indexed by higher HRV.

Another 2010 study led by Ullén's colleague, Örjan de Manzano, “The Psychophysiology of Flow During Piano Playing,” found that professional pianists were able to immediately activate the parasympathetic system in the difficult prima vista "sight reading" situation of playing unknown music. The researchers of this study concluded,

“It appears possible, therefore, that the ability of experts to regulate the level of activity in both sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomous nervous system during performance is of importance for state flow, but further research is obviously needed to test this idea.

Furthermore, as we speculated above, parasympathetic mechanisms may be of importance for flow. During recent years, it has been pointed out that activation of the parasympathetic system is helpful in the recovery phase after an arousal reaction and that this stops inflammatory reactions that stimulate, for instance, the atherosclerotic process. The ability to activate the parasympathetic system could thus be of importance for flow as well as long-term health and longevity."

The final study I’m going to include in this analysis of the psychophysiology of flow is, "The Relation of Flow-Experience and Physiological Arousal Under Stress—Can U Shape It?" from 2014. In this study, Corinna Peifer and colleagues in Germany found that a co-activation of both branches of the autonomic nervous system appear to facilitate task-related flow.

Again, coactivation of the autonomic branches during flow was measured by sympathetic and parasympathetic activation using measures of heart rate variability (HRV). The researchers identified a positive relationship of parasympathetic activation with flow-experience as measured through the flow-scale absorption. According to the researchers, “The association of flow with increased parasympathetic activation found in this study suggests a decrease of cognitive workload during flow.”

Fredrik Ullén cautions that more research is needed before drawing any set-in-stone conclusions about the psychophysiology of flow, given that so few studies have been performed. Please stay tuned for more research on this topic and my final entry in this series, "Paying It Forward: Generativity and Your Vagus Nerve."

References

Eric Brymer, Robert D. Schweitzer. Evoking the ineffable: The phenomenology of extreme sports. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2017; 4 (1): 63 DOI: 10.1037/cns0000111

Paul K. Piff, Pia Dietze, Matthew Feinberg, Daniel M. Stancato, Dacher Keltner. Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2015; 108 (6): 883 DOI: 10.1037/pspi0000018

Michelle N. Shiota, Dacher Keltner, and Amanda Mossman. The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Pages 944-963 | Received 22 Sep 2005, Published online: 19 Jul 2007. Cognition and Emotion. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699930600923668

Lang, Peter J.The emotion probe: Studies of motivation and attention. American Psychologist, Vol 50(5), May 1995, 372-385. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.50.5.372

Ullén, Fredrik de Manzano, Örjan Theorell, Töres, Harmat, Lazlo. The Physiology of Effortless Attention: Correlates of State Flow and Flow Proneness. April 2010 DOI: 10.7551/mitpress/9780262013840.003.0011 In book: Effortless attention: a new perspective in the cognitive science of attention and action, Publisher: The MIT Press, Editors: Brian J. Bruya, pp.205-218

de Manzano, Theorell T, Harmat L, Ullén F. The psychophysiology of flow during piano playing. Emotion. 2010 Jun;10(3):301-11. doi: 10.1037/a0018432.

Corinna Peifera, André Schulzb, Hartmut Schächingerb, Nicola Baumannd, Conny H. Antonia. The relation of flow-experience and physiological arousal under stress — Can u shape it? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. Volume 53, July 2014, Pages 62–69. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.01.009