Sport and Competition

Superfluidity and the Transcendent Ecstasy of Extreme Sports

New research debunks the myth that extreme athletes are just adrenaline junkies.

Posted May 10, 2017

A revelatory new study on the psychological factors that motivate extreme athletes to risk their lives in the pursuit of a transcendent experience debunks the myth that these people (myself included) are simply adrenaline junkies with a death wish. This paper, "Evoking the Ineffable: The Phenomenology of Extreme Sports," was published May 9 in the journal Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice.

The title of this study (in and of itself) reveals many clues about what makes this research so refreshing and unique. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first time sports psychologists have explored the phenomenology of extreme sports and the "hard-to-describe" aspects of experiencing heightened states of consciousness while pushing against one's limits as an extreme athlete. Fascinating stuff!

Co-authors Eric Brymer, who is currently based at Leeds Beckett University in the UK, and Robert Schweitzer of the Queensland University of Technology in Australia were curious to identify the psychological and spiritual underpinnings that motivate athletes to go to extremes. So, they conducting in-depth interviews with a wide range of men and women from around the globe who participated in various extreme sports.

Eric Brymer specializes in the psychology of adventure racing and extreme sports with a specific focus on the sense of awe that one experiences in nature. As a public health advocate and conservationist, Brymer’s dual-pronged mission is to promote the physical and psychological health benefits of playing sports and physical activity. He also hopes that the positive associations with nature created during outdoor activity will lead to more widespread environmental advocacy and protection.

Robert Schweitzer's academic focus is on postgraduate teaching. He specializes in psychodynamic theory, clinical psychopathology, and interventions as well as psychotherapy process.

Their latest international study involved interviews with 15 extreme sports participants from multiple continents. The research duo unearthed three universal themes: (1) extreme athletes experience a sense of transcendence (2) extreme sports is an invigorating experience (3) participants struggled to find words or language to adequately describe the profound states of consciousness they had experienced during extreme sports.

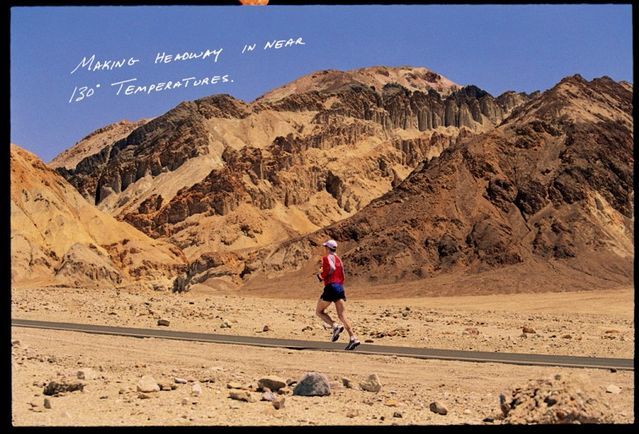

In recent years, the popularity of extreme sports has skyrocketed. While many traditional recreational sports have seen a reduction in participation, extreme sports—such as ultramarathon running in harsh climates, BASE jumping, big wave surfing, solo rope-free climbing, etc.—have become a worldwide phenomenon and multi-million dollar industry.

In the abstract to their latest study, Brymer and Schweitzer note “Extreme sports are unique in that they involve physical prowess as well as a particular attitude toward the world and the self. The findings provide a valuable insight into the experiences of the participants and contribute to our understanding of human volition and the range of human experiences.”

The latest research on human transcendence during extreme sports activities in the great outdoors dovetails with recent findings on the nature-inspired power of awe by Paul Piff of the University of California, Irvine. In a 2015 study, “Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior,” Piff and colleagues found that the sense of wonder experienced in nature (i.e. visiting the Giant Redwoods in the Sequoia Forest) was a catalyst for having a "wow!" moment that was accompanied by the realization that there was something much bigger than one's "small self" in the universe.

Prior to identifying these hitherto unknown common themes amongst extreme athletes, Brymer and Schweitzer had a hunch that the pursuit of extreme sports was about much more than just getting a rush of adrenaline. In a statement, Schweitzer said,

"Far from the traditional risk-focused assumptions, extreme sports participation facilitates more positive psychological experiences and express human values such as humility, harmony, creativity, spirituality, and a vital sense of self that enriches everyday life. So rather than a theory based approach which may make judgments that don’t reflect the lived experience of extreme sports participants, we took a phenomenological approach to ensure we went in with an open mind."

Brymer added, "Our research has shown people who engage in extreme sports are anything but irresponsible risk-takers with a death wish. They are highly trained individuals with a deep knowledge of themselves, the activity and the environment who do it to have an experience that is life enhancing and life changing. The experience is very hard to describe in the same way that love is hard to describe. It makes the participant feel very alive where all senses seem to be working better than in everyday life, as if the participant is transcending everyday ways of being and glimpsing their own potential.”

The researchers decided to focus on the personal first-person experiences of extreme athletes and adventure sports enthusiasts with the ultimate goal of identifying recurring themes that were consistent across the participants’ various self-described accounts. The researchers state, “By doing this we were able to, for the first time, conceptualize such experiences as potentially representing endeavors at the extreme end of human agency, that is making choices to engage in activity which may in certain circumstances lead to death."

Last night, when I read this study for the first time, I said to myself out loud,"Yes! That's it." This empirical evidence identifies universal themes in extreme sports that I can anecdotally corroborate based on years of ultra-endurance running, triathlon, and adventure racing in which I experienced invigorating and transcendent ecstasy that is very hard to describe. Notably, the word “ecstasy” comes from the Greek "to stand outside oneself.”

As an ultra-endurance athlete, I spent decades tapping into the transcendent aspects of extreme sports while doing things such as running 135-miles nonstop through Death Valley in July, competing in countless Ironman triathlons around the globe, winning three back-to-back "Triple" Ironmans (7.2-mile swim, 336-mile bike, 78.6-mile run) in 38 hours and 46 minutes, and breaking a Guinness World Record by running 153.76 miles in 24 hours. Based on my life experience, the poignant new research by Brymer and Schweitzer on the power of extreme sports to evoke indescribable transcendent states of consciousness struck a deep chord.

In language that I could relate to, one of the BASE jumpers in this study described being able to see all the colors within the nooks and crannies of a cliff in slow motion, even though he was free falling at 186 mph. Extreme rock climbers described the sensation of "floating and dancing with the rock." Other extreme athletes in the study talked about their perception of time completely slowing down and a feeling that their entire being had merged with nature.

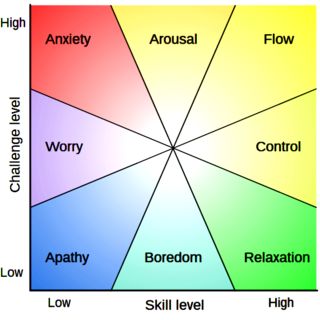

At first glance, many people who are familiar with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's concept of "flow" would tag these experiences as being categorized as occurring within the "flow channel" in which a high skill level is perfectly matched to a high level of challenge. However, based on extensive research and my own life experience as an extreme athlete, I have a hypothesis that it's important to divide the flow experience into two tiers: (1) Flow and (2) Superfluidity. Flow is more readily available (which is a good thing). Superfluidity occurs within the flow channel but is more episodic, ecstatic, and extreme. Which makes it seemingly more exotic and "otherworldly."

Flow is a blissful, rewarding, and contented state of consciousness that occurs when a person 'loses' him or herself in an activity. Flow is often referred to colloquially as being "the zone." As mentioned earlier, I use the concept of "superfluidity" to describe an elevated, second-tier of the flow experience. Technically, in the world of physics, superfluidity is defined as “the property of flowing without friction or viscosity.”

I believe that differentiating flow from superfluidity is helpful for demystifying a regular state of flow and making the process of achieving an everyday flow state more accessible to people from all walks of life and skill levels. It's also helpful to have new vernacular to describe higher states of consciousness to avoid the "ineffable" lack of descriptive language within the phenomenology of extreme sports.

Unfortunately, I believe, these two tiers of the flow experience are constantly being muddled together because—as the title of the new study on how extreme sports "evoke the ineffable" makes clear—people do not have nuanced language to clearly describe varying degrees of extraordinary and uncommon states of consciousness.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi first defined flow in his seminal book Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play (1975). He later acknowledged that “there seems to be a need to reinvent or re-express the answer of what to do to create flow every couple of generations.” Unfortunately, until now, there hasn't been much cutting-edge academic research that puts the need for new language and lexicography to describe ineffable aspects of peak experiences of heightened states of consciousness in sport and life.

For some background on how I became fascinated with deconstructing the flow experience: After years and years of achieving a state of flow most days of the week during my athletic training and sports competitions, entering the flow channel became de rigeur and lost its mystique. Of course, I will always be eternally grateful to Csikszentmihalyi for pinpointing the "between boredom and anxiety" equation and making it easy to apply actionable advice by following the simple diagram above. But, after much more than 10,000 hours of "deliberate practice" inside the flow channel, it became predictable in a formulaic "add water and stir" kind of way.

As I practiced religiously every day to become an elite-level athlete, creating flow became mechanical, mundane, and par for the course on a daily basis. That said, creating a state of flow is always going to be the launching pad that helps someone pierce through to another stratosphere of consciousness during extreme sports.

During this time, what really got my juices going inside the flow channel were these episodic moments of feeling absolutely zero friction, viscosity, or entropy within my body, mind, and the world around me. More than crossing a finish line, chasing the pure bliss of these ecstatic "out of body" experiences when I would "stand outside myself" became like the pursuit of the proverbial "Holy Grail" for me as an ultra-endurance athlete. Interestingly, this feeling of total connectedness reminded me of taking psilocybin in high school and was like a drug in and of itself. Needless to say, I became fanatically hooked.

In my search for empirical evidence to explain these miraculous and somewhat mystical experiences, of feeling as if I was a conduit tapped into some infinite and cosmic energy force as an extreme athlete, I discovered the work of Marghanita Laski. In 1969, she published one of my all-time favorite books, Ecstasy: In Secular and Religious Experiences.

For this book, Professor Laski created a detailed questionnaire of “where, when, and why” various people experienced secular or religious ecstasy. Much like Brymer and Schweitzer in 2017...Almost five decades ago, Laski was able to identify and isolate common themes of when people felt an ecstatic sense of oneness with a spiritual “Source."

Laski classified an experience as an “ecstasy” if it possessed two of the three following: unity, eternity, heaven, new life, satisfaction, joy, salvation, perfection, glory; contact, new or mystical knowledge; and at least one of the following feelings: loss of difference, time, place...or feelings of calm, worldliness, and peace. Her survey also included questions such as, “Do you know a sensation of transcendent ecstasy? How would you describe it?"

Respondents to Marghanita Laski's survey used a variety of similar phrases when describing the spiritual connections they experienced during transcendent ecstasies, such as:

"A sense of the oneness of things, you understand that everything in reality is connected to one thing ... I saw nothing and everything ... All the separate notes have melted into one swelling harmony ... I saw and knew the being of all things in that moment ... The inner and outer meaning of the earth and sky and all that is in them ... I fit exactly ... I saw the Divine universe is a living presence in everything.”

Laski also found that the most common triggers for transcendental ecstasies came from nature: water, for instance, and mountains, trees, and flowers; dusk, sunrise, sunlight; dramatically bad weather. Again, this corroborates Brymer's mission for nature conservancy and Piff's research on awe and the small self. All of the aforementioned triggers for "ecstasy" in Laski's survey have the ability create a feeling of self-transcendence. I would add extreme sports and any type of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) to this list.

Even after reading Laski's enlightening book, I still had my antennae up for more specific terminology to help describe the "ineffable" orgasmic waves of feeling as if I had completely transcended the mundane constraints of the work-a-day world during extreme sports. I wanted to be able to tag this state of consciousness as a specific Nirvana-esque place and correlate when and where it happened so that I could purposely return to this wonderland in my mind. Luckily, in my ongoing quest to find more descriptive language to describe the highest tier of flow, I was fortunate enough to stumble on a BBC special about the history of 20th-century physics.

Although equating extreme sports, transcendent ecstasy, and quantum physics may seem kind of esoteric, the BBC provided visualizations that worked for me. Especially, because the video below made an abstract, metaphysical state of consciousness that seemed kind of new-agey and "woo-woo" more tangible by grounding it in science.

Additionally, the BBC video (above) of helium doing supernatural things in a lab made the empiricist in me more open to pursuing superfluidity during extreme sports. My logic was: "If I can observe this type of reality-defying phenomenon in a scientific laboratory under specific conditions, why can't I use extreme sports to go to the same place in an "Alice in Wonderland" parallel universe by using extreme sports and my imagination to create a type of mystical "looking glass" in the natural world?"

Believing in superfluidity as a state of consciousness created a self-fulfilling prophecy and an explanatory style for negating the doubt of naysayers (often within my own head) who tried to persuade me that I was setting out to do things as an extreme athlete that were physically impossible or would kill me.

From a pop culture perspective, for me, the archetypal importance in the "Hero's Journey" of returning home to the ordinary world after extraordinary adventures is summed up in the Bruce Springsteen coming of age (and then entering adulthood) anthem "Growin' Up." The lyrics to this song remind me that ultimately you have to come back down to earth and return home in one piece to complete the monomyth. Springsteen sings, "I took month-long vacations in the stratosphere, and you know it's really hard to hold your breath. I swear I lost everything I ever loved or feared, I was the cosmic kid in full costume dress. Well, my feet they finally took root in the earth, but I got me a nice little place in the stars."

As an ultra-endurance athlete in my prime, I lived by the motto "Excelsior" (Latin for "ever higher"). This was both a blessing and a curse. For example, anytime I returned home from an exotic adventure or achieved what I thought was an unfathomable goal, I'd wake up the next day with a colossal sense of emptiness, hopelessness, and the malcontent of an existential letdown. I'd say to myself in the third person, "What now, Chris? How are you ever going to exceed that level of challenge and live to tell about it?"

Then, I would be consumed by apathy and fall into a cynical, jaded state of what I call Peggy Lee "Is That All There Is?" syndrome. The catch-22 of mastering high levels of challenge and skill is that once you summit your personal Everest, there is no place higher to go. So, I had to keep raising the bar and taking on more and more insanely extreme challenges which began to destroy my body.

Even if you're not an adrenaline junkie with a death wish, there is a potential dark side to extreme sports. My insatiable pursuit of transcendent athletic ecstasy through extreme sports became like pursuing a 'holy grail' or a golden ring that was always just slightly out of reach.

In my case, this pursuit ultimately almost killed me due to complications from kidney failure. I've since bounced back, but made a vow when I became a parent that I would never push my body to the brink of self-annihilation again or be consumed by "summit fever." (I write about the underbelly of pathologically pursuing superfluidity in a Psychology Today blog post "The Dark Side of Mythic Quests and the Spirit of Adventure.")

On the bright side, Professor Schweitzer and Brymer remind us that the psychological motivations for extreme sports are important for understanding humans nature and can be transformative at various stages of life. Schweitzer concludes, "Such experiences have been shown to be affirmative of life and the potential for transformation. Extreme sport has the potential to induce non-ordinary states of consciousness that are at once powerful and meaningful. These experiences enrich the lives of participants and provide a further glimpse into what it means to be human." I agree.

References

Eric Brymer, Robert D. Schweitzer. Evoking the ineffable: The phenomenology of extreme sports.. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2017; 4 (1): 63 DOI: 10.1037/cns0000111

Paul K. Piff, Pia Dietze, Matthew Feinberg, Daniel M. Stancato, Dacher Keltner. Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2015; 108 (6): 883 DOI: 10.1037/pspi0000018